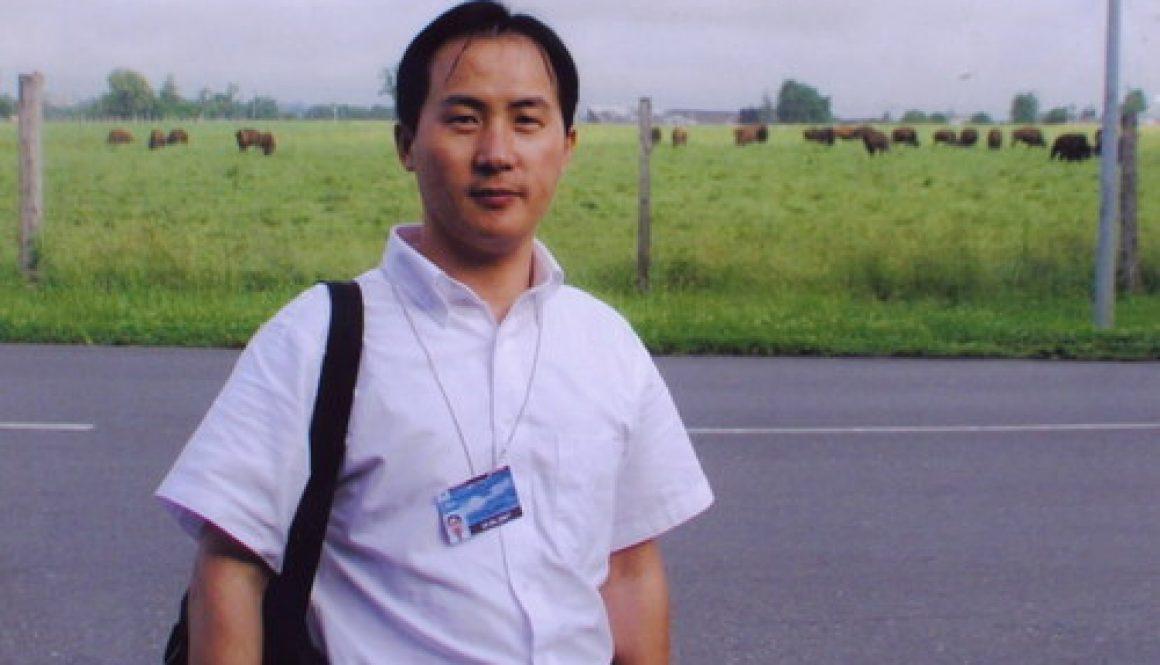

After nearly two years behind bars, Li Heping, a prominent Chinese human rights lawyer, was released from prison last week.

Both his friends and his wife said he was barely recognizable—once robust and healthy, he is now thin and emaciated, his hair turned white, a radical transformation for someone only in his mid-forties.

On July 9, 2015, he was taken away by Tianjin public security officers and sentenced with “subversion of state power.” His arrest was part of a nationwide crackdown in 2015—known colloquially as the “709 Incident”—which targeted over 250 human rights lawyers and activists.

After two years of painstaking advocacy on his behalf, Wang Qiaoling, Li’s wife, was finally able to secure his release. Li was given a four-year suspended sentence, which means he still cannot practice law as before.

Representing the Vulnerable

Li Heping garnered prominence for defending political dissidents and vulnerable groups in China, including underground Christians, victims of forced evictions, as well as practitioners of the persecuted Falun Gong spiritual practice.

He also sought to appeal on behalf of blind activist Chen Guangcheng and fellow rights attorney Gao Zhisheng. In 2006, he defended environmental activist Tan Kai, founder of the environmental group “Green Watch.”

In 2007, Li and five other Beijing-based human rights lawyers represented Wang Bo, a Falun Gong practitioner, in a prominent case in Shijiazhuang City. In their defense of Wang Bo’s innocence, they jointly published “The Constitution is Supreme, Freedom of Religion” — the first time Chinese lawyers applied Chinese law to systematically defend Falun Gong practitioners as innocent. The defense statement would be frequently referenced by rights lawyers later on when representing other Falun Gong practitioners.

As he continued to take on high-profile cases, Li was subjected to increasing harassment, surveillance, and threats by Chinese security forces.

In September 2007, Li was abducted by plainclothes police and shocked with electric batons for several hours before being left in the woods in the suburbs of Beijing.

In 2009, Chinese authorities refused to renew Li’s law license, thus depriving him of his right to practice law and forcing him to turn to legal consultation work instead.

Mounting tensions culminated with Li Heping’s arrest in July 2015 along with numerous other human rights defenders.

From Defender to Persecuted

According to Li’s wife, Wang Qiaoling, Li was subjected to constant surveillance while detained—with people guarding him even as he used the bathroom—and tortured with beatings and electric shocks.

Furthermore, while imprisoned, Li was regularly forced to consume unknown drugs, ostensibly for high blood pressure, a condition he did not have.

The drugs resulted in bodily weakness, pain in his muscles, and blurry vision. Other human rights defenders released from prison, including Li’s younger brother, Li Chunfu, have discussed similar experiences of being force-fed unknown medication while detained. After being released in January 2017, Li was soon diagnosed with symptoms of schizophrenia.

According to Heng He, a senior political commentator at New Tang Dynasty Television (a sister media company of Epoch Times) the use of drugs as a form of torture is not an isolated occurrence. In 2001, the American Psychiatric Association began drawing attention to forced administration of psychotropic drugs on Falun Gong practitioners detained at mental hospitals.

Heng says that the force-feeding of drugs was “used at a large scale on Falun Gong practitioners before being used to persecute human rights lawyers.” The purpose, he says, is to “break their will” and to threaten those around them by highlighting the consequences of opposing state policy.

In response to mounting evidence of forced administration of drugs, members of Chinese Lawyers for the Protection of Human Rights penned an open letter on May 14 calling for an independent investigation into the use of drugs to torture rights lawyers imprisoned as a part of the 709 Incident.