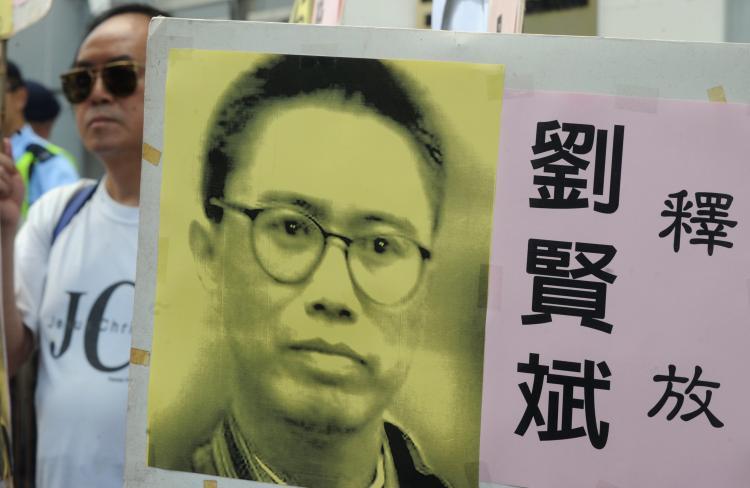

Chinese dissident Liu Xianbin was paraded into court on Friday and after two hours sentenced to ten years in prison. Liu had been convicted with the vague but perilous charge of “inciting subversion of state power,” through essays he had written advocating democracy.

The judge in the Suining court in Sichuan Province repeatedly interrupted Liu as he attempted to make a statement, his wife told various Western media outlets in China. But he managed to cry out “I’m not guilty.”

Observers see the harsh sentence as part of an overall attempt, ramped up in recent years, to extinguish the growing cohort of human rights lawyers, democracy activists, and other voices calling for civil society in China.

“It’s actually very simple. It’s the same thing they’ve been doing over the last several years. They want to smash this group of people,” said Guo Guoting, a Chinese civil rights lawyer who now lives in Canada, in a telephone interview.

“The Party-state is deepening in its lawlessness, really,” said Kelley Currie, a Senior Fellow with the DC-based Project 2049 Institute, a thinktank. “It’s part of a broader trend where you’re seeing them completely intolerant of dissent, anything that overtly challenges the system or talks about the illegitimacy of the CCP leadership,” she said.

Joshua Rosenzweig of Duihua Foundation, a group focused on civil rights in China, wrote something along the same lines in the Wall Street Journal on March 24: “Compared to earlier suppression campaigns, this one is more terrifying because of its blatant lawlessness.”

Liu’s case is slightly different in that the law was ostensibly used. But there are immense problems in even the legal trappings with which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has attempted to gild the punishment, Guo says.

“Even going according to the CCP’s standards, it’s a judgment that entirely perverts the law,” Guo wrote in an email. He pointed out that the language in article 105 of the Chinese penal code, which deals with subversion of state power, implies the use of violence. “But Liu Xianbin never did anything remotely violent,” he wrote.

The particular charge has been used by the authorities for years, and has been subject to lengthy dissection by human rights groups.

In 1998 Liu was part founder of the China Democracy Party’s Sichuan chapter. The group did not last long, however, and in 1999 Liu was sent to prison for 13 years. The charge was, like this time, “subversion of state power.”

Other democracy groups founded in more recent years have faced the same harsh dismantling. Guo Quan, another democracy activist who founded the China New Democracy Party, is in his third year of a 10-year sentence handed down in 2009.

After Liu was released on Nov. 6, 2008, he went back to his democracy activism. Essays he penned for overseas dissident publications aroused the CCP’s ire, and he was detained on June 27, 2010.

The following month Party prosecutors compiled a list of his statements as evidence against him. He had written that “the rule of the Communist Party has always been characterized by high pressure and terror,” and that the Chinese people live under “the terrorizing rule of the political police, living their lives mechanically like slaves.”

This was “slander of the People’s Democratic Dictatorship,” the prosecutors said.

Guo, formerly a lawyer, regards the sentence as a strong signal by the authorities to Liu’s peers. He used the well-worn Chinese phrase: “killing the chicken to scare the monkeys.”

Many see in the authorities’ increasingly fierce tactics a kind of desperation.

Since 2008 the Party went from the usual fears about its legitimacy to being “completely freaked out,” Kelley Currie said in a telephone interview. “It’s a low trust regime, their legitimacy is rooted in things that are extremely transient,” she said.

With an unbalanced economy suffering structural problems, an uptick in social unrest, and a civil society that is attempting to emerge, the Party is having a harder time holding onto the mechanics of power, Currie said.

“There’s been a steady succession of things that have just spooked them in a very serious way,” she said, making the recent blow dealt to Liu “unsurprising.”

Zheng Cunzhu, longtime democracy activist and organizer of the China Democracy Party in California, doesn’t think the repression is going to help. “The more they do this, the more you can see it’s not working,” he said to The Epoch Times over the telephone.

He added: “The one-party dictatorship wants to create a ‘harmonious society,’ but the monopolies and injustices are unavoidable. Ordinary people start from defending just their own rights,” before gradually realizing that “unless there’s a change to the system, they’ll never have their rights,” he said.

“The world wants democracy. There’s no way to stop it,” he said.

The tight-knit community of rights activists in China is doing what they can. On Twitter they circulated the bank account number of Liu’s wife, calling for direct donations.

The judge in the Suining court in Sichuan Province repeatedly interrupted Liu as he attempted to make a statement, his wife told various Western media outlets in China. But he managed to cry out “I’m not guilty.”

Observers see the harsh sentence as part of an overall attempt, ramped up in recent years, to extinguish the growing cohort of human rights lawyers, democracy activists, and other voices calling for civil society in China.

“It’s actually very simple. It’s the same thing they’ve been doing over the last several years. They want to smash this group of people,” said Guo Guoting, a Chinese civil rights lawyer who now lives in Canada, in a telephone interview.

“The Party-state is deepening in its lawlessness, really,” said Kelley Currie, a Senior Fellow with the DC-based Project 2049 Institute, a thinktank. “It’s part of a broader trend where you’re seeing them completely intolerant of dissent, anything that overtly challenges the system or talks about the illegitimacy of the CCP leadership,” she said.

Joshua Rosenzweig of Duihua Foundation, a group focused on civil rights in China, wrote something along the same lines in the Wall Street Journal on March 24: “Compared to earlier suppression campaigns, this one is more terrifying because of its blatant lawlessness.”

Liu’s case is slightly different in that the law was ostensibly used. But there are immense problems in even the legal trappings with which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has attempted to gild the punishment, Guo says.

“Even going according to the CCP’s standards, it’s a judgment that entirely perverts the law,” Guo wrote in an email. He pointed out that the language in article 105 of the Chinese penal code, which deals with subversion of state power, implies the use of violence. “But Liu Xianbin never did anything remotely violent,” he wrote.

The particular charge has been used by the authorities for years, and has been subject to lengthy dissection by human rights groups.

In 1998 Liu was part founder of the China Democracy Party’s Sichuan chapter. The group did not last long, however, and in 1999 Liu was sent to prison for 13 years. The charge was, like this time, “subversion of state power.”

Other democracy groups founded in more recent years have faced the same harsh dismantling. Guo Quan, another democracy activist who founded the China New Democracy Party, is in his third year of a 10-year sentence handed down in 2009.

After Liu was released on Nov. 6, 2008, he went back to his democracy activism. Essays he penned for overseas dissident publications aroused the CCP’s ire, and he was detained on June 27, 2010.

The following month Party prosecutors compiled a list of his statements as evidence against him. He had written that “the rule of the Communist Party has always been characterized by high pressure and terror,” and that the Chinese people live under “the terrorizing rule of the political police, living their lives mechanically like slaves.”

This was “slander of the People’s Democratic Dictatorship,” the prosecutors said.

Guo, formerly a lawyer, regards the sentence as a strong signal by the authorities to Liu’s peers. He used the well-worn Chinese phrase: “killing the chicken to scare the monkeys.”

Many see in the authorities’ increasingly fierce tactics a kind of desperation.

Since 2008 the Party went from the usual fears about its legitimacy to being “completely freaked out,” Kelley Currie said in a telephone interview. “It’s a low trust regime, their legitimacy is rooted in things that are extremely transient,” she said.

With an unbalanced economy suffering structural problems, an uptick in social unrest, and a civil society that is attempting to emerge, the Party is having a harder time holding onto the mechanics of power, Currie said.

“There’s been a steady succession of things that have just spooked them in a very serious way,” she said, making the recent blow dealt to Liu “unsurprising.”

Zheng Cunzhu, longtime democracy activist and organizer of the China Democracy Party in California, doesn’t think the repression is going to help. “The more they do this, the more you can see it’s not working,” he said to The Epoch Times over the telephone.

He added: “The one-party dictatorship wants to create a ‘harmonious society,’ but the monopolies and injustices are unavoidable. Ordinary people start from defending just their own rights,” before gradually realizing that “unless there’s a change to the system, they’ll never have their rights,” he said.

“The world wants democracy. There’s no way to stop it,” he said.

The tight-knit community of rights activists in China is doing what they can. On Twitter they circulated the bank account number of Liu’s wife, calling for direct donations.