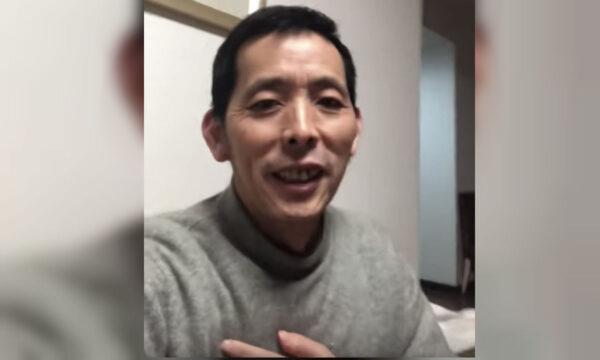

Li Zehua, 25, was one of three citizen journalists who went missing in Wuhan.

A video he published on Feb. 20 showed temporary porters being hired to transport corpses of people who apparently died of the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) virus, commonly known as the novel coronavirus. It was viewed 850,000 times on YouTube, which is blocked in China.

Days later, he posted live video of the police coming to his home. He was then not heard of until his new video was posted April 22.

The other two citizen journalists, Chen Qiushi and Fang Bin, who according to media reports posted footage of overwhelmed hospitals and corpses piled in a minibus, haven’t resurfaced publicly.

Chen’s mother said earlier he was missing, while Fang also posted a video of the police knocking on his door.

Chinese authorities made no public comment about any of the three.

On March 31, U.S. Rep. Jim Banks (R-Ind.) called on the U.S. State Department to urge China to investigate the disappearance of the three.

Li, in his new video posted April 22, said police took him from his apartment in Wuhan on Feb. 26 and questioned him at a local facility on suspicion of disrupting public order.

He said that after nearly 24 hours, the police station chief told him he wouldn’t be charged but would need to be quarantined because he had been to high-risk areas, such as a crematorium.

Li said he was quarantined in a hotel until March 14, and then escorted to his hometown, where he was quarantined for another 14 days. He said police had required that he give his electronic devices to a friend while he was in quarantine.

It isn’t clear why Li chose to post the new video recounting his experience, which he said was made on April 16, three weeks after his last quarantine ended.

Li didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment and Wuhan police couldn’t immediately be reached for comment on April 23.

In the YouTube video recorded in late February, moments before Li opened the door to police, the former state television employee spoke about his ambition to speak up on behalf of the people.

He also lamented what he said was a dearth of idealism among young people and used a euphemism to refer to student protests that led to a crackdown in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989, a taboo subject for China’s ruling Communist Party.