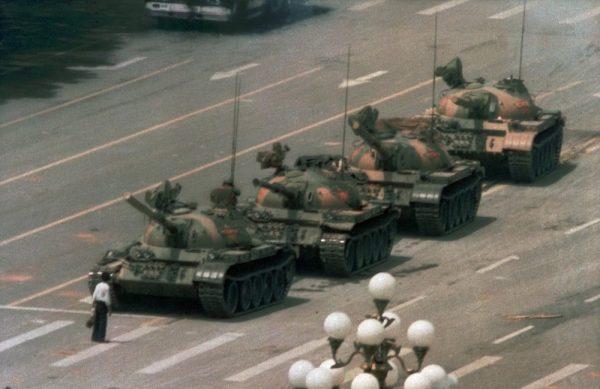

The first armored truck appeared around 11 p.m. on June 3, 1989. Around 1:30 a.m., gunshots were fired. The sound of gunfire continued through the night as tanks rolled in, crushing people and objects that were in their way.

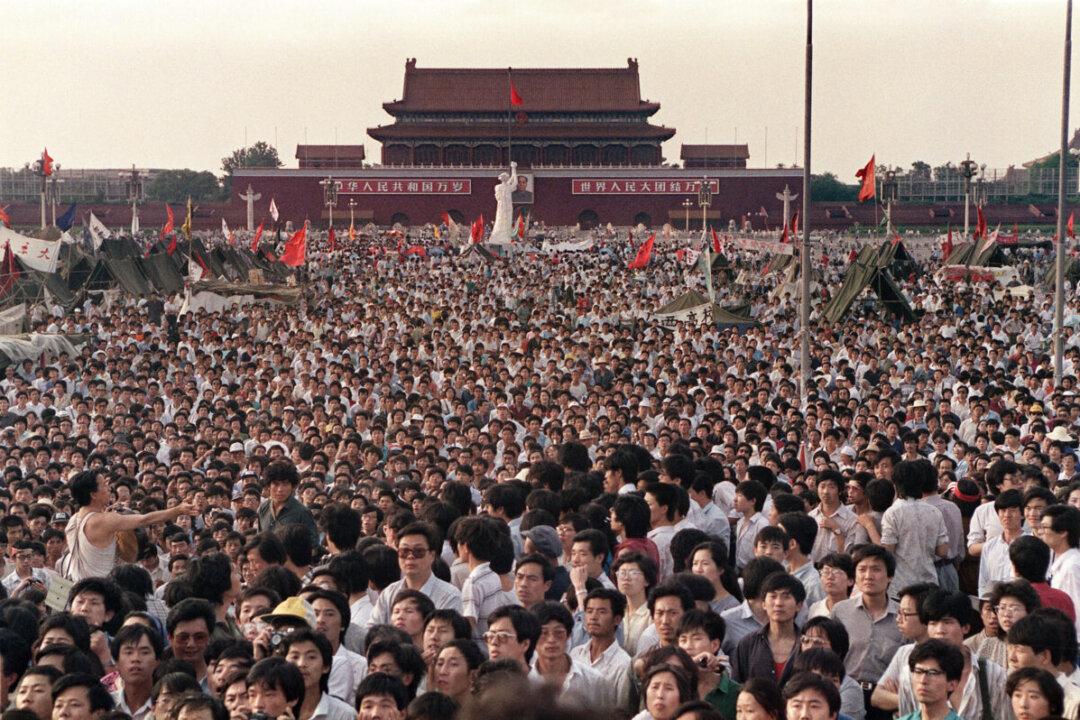

It was a night of chaos at Tiananmen Square: Bullets flying overhead as people fell, and panicked protesters propped limp bodies onto bikes, buses, and ambulances to ferry them away. Thousands of pro-democracy protesters are estimated to have died.

Lily Zhang was head nurse at a Beijing hospital about a 15-minute walk away from the city square. She woke up to the sound of gunfire. Another nurse, sobbing, told her the pool of blood from injured protesters was “forming a river at the hospital.”

Three decades on, the bloodshed that became known as the Tiananmen Square massacre has continued to haunt the survivors, many of whom have fled communist China for greater freedom. They hope that by speaking up about what happened that fateful day, the public will always remember what was lost.

Fateful Night

The Tiananmen Square protests, a youth-led movement advocating for democratic reforms, have become a taboo subject in China. To this day, the Chinese communist regime won’t disclose the number or names of those killed in the clampdown.Zhang, who had stayed at the square to care for the students on hunger strike until the night of June 3, rushed to the hospital in the morning upon hearing of the massacre. She was horrified when she arrived at her hospital to find a “warzone-like” scene.

After the clampdown began, ambulances from all 30 city hospitals were mobilized. Injured students filled every hospital bed, with some having to share between two persons. Their blood stained the lobby floor, hallways, and stairs. At Zhang’s hospital, at least 18 had died by the time they were carried into the facility.

The soldiers used “dum dum” bullets, which would expand inside one’s body and inflict further damage, Zhang noted. Many sustained grave wounds and were bleeding so profusely that it was “impossible to revive them.”

At the hospital gate, a critically injured reporter with the state-owned China Sports Daily told the two health workers who carried him that he “didn’t imagine that the Chinese Communist Party would really open fire.”

“Shooting down unarmed students and commoners—what kind of ruling party is this?” were the last words he left to the world, Zhang recalled.

A journalist at the national news magazine Beijing Review at the time, Lou stood at a nearby street, watching what he called a “fateful night” unfold with the feeling of witnessing history.

“It’s a tragedy,” he said, adding that it was “the start of the moral decline of China.”

“The Chinese government led by communists turned its back against its own people,” Lou said. Those who made sacrifices “were punished instead of rewarded. What message is the country sending to its own people?” Many of the student activists involved in the movement were jailed in the wake of the Massacre.

Zhou Fengsuo, a student leader during the protests, counted 40 dead bodies in the early hours of June 4 as he walked from Tiananmen Square to Tsinghua University, where he was studying.

Before leaving the square, Zhou made a short speech vowing that pro-democracy protesters would make a comeback someday. “I felt when the regime has resorted to violence against people, they have lost the moral high ground,” he told The Epoch Times.

Zhang, who was 28 at the time and designated by the local government as a “model worker,” thought she would “resolutely love the nation and the Party.” But that day, she wept with her coworkers, saying the devastation had “chilled her heart.”

Aftermath

The sense of distrust only deepened after Chinese officials quickly denounced the protesters as rioters, and claimed that “no one was shot dead during the Tiananmen Square cleanup.” The government roundup came soon after.Zhou, a student at a top university, spent one year in jail and was not allowed to go back to school.

At Zhang’s hospital, a meeting was called, requiring everyone to “take a stance” by stating there were no deaths. But the staff uniformly refused to attend the meeting.

“We all thought: who can utter such words against their conscience?” she said.

Two prominent news anchors at state broadcaster CCTV were demoted and removed from their posts after they wore black while reporting on the massacre on June 4. Beijing Review’s editor-in-chief also resigned to protect his staff, who had previously staged peaceful protests in support of the students. Nonetheless, Lou became a “key target” and was investigated for his “role” in the movement.

All three have since made their way to the United States, seeing no hope in a future under communist China.

Remembrance

The clampdown, the witnesses said, is a reminder of the Chinese regime’s brutality. Today, it is evidenced by authorities’ coverup of the CCP virus outbreak, which has left the world suffering, they said.“A totalitarian regime will pose harm to all,” Zhou said.

Kenneth Lam, who traveled to Beijing to join the protests in May 1989 and stayed until June 4, was sitting on top of a monument in the center of the square that morning when armed soldiers rushed up. The protesters from Beijing pulled him away. Calling him by the nickname “Xiao Qiang,” they asked him to “go back alive, and tell this to the world.”

Working as a volunteer lawyer for Hong Kong protesters last year, Lam saw a similarity in the willingness of protesters from both movements to sacrifice their futures for the greater good.

At Tiananmen Square, hundreds had put on red scarves to participate in a hunger strike, while in Hong Kong, young protesters come to the streets to safeguard the city’s autonomy and freedoms, putting their safety and future careers on the line, Lam said.

“It’s a very bright and beautiful side of human nature,” he said.

This “striking similarity” 31 years later, Lam said, is evidence that there’s something within people more enduring than power and coercion.

“Authoritarian rule can never crush the bright side of human nature,” he said.