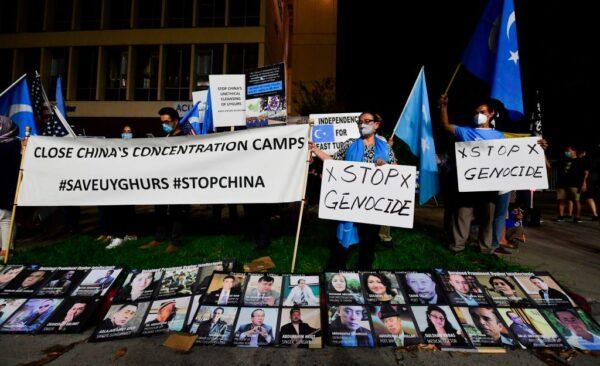

Early in February, the BBC broadcast interviews with several Uighur women who graphically described the horrific treatment they'd received while detained in one of the concentration camps where China has reportedly locked up a million or more ethnic Muslims for “vocational training” and “deradicalization.”

China’s response was swift and predictable. It accused the BBC of passing along “fake news” about Xinjiang, the COVID epidemic and other matters. The BBC, China’s authorities said, had “seriously violated” regulations that news broadcasts be “truthful and fair.” Chinese newspapers also dutifully passed on an accusation against the network from a British journalist and academic named John Ross. Ross claims that the BBC is largely controlled by the British intelligence service MI5, which, according to Ross, directly “vets” all members of the broadcaster’s staff.

The Chinese press cited a tweet in which Ross said that “coordination of the BBC with military intelligence,” had come “from a special office inside BBC headquarters.”

China often turns to foreign “experts” such as Ross to supply credibility for its persistent complaint that the Western media is “anti-China” and in cahoots with foreign governments, especially the United States. Ross is one of several foreigners, generally attached to Chinese universities or research institutes, who have emerged as apologists for Beijing, especially as it has come under intensifying criticism for its human rights violations in Xinjiang and Hong Kong and its ever tighter control of opinion across the country.

There are other commentators on China with views more moderate and nuanced than those of Ross, and who publish books as well as articles in Western and Chinese publications. These commentators would be unlikely to attack a reputable news organization like the BBC or to justify banning it from broadcasting to China.

But both types of foreign experts often echo the arguments made by China’s state-controlled media, especially their constant claim that China’s one-party state is a brilliantly successful alternative to Western-style liberal democracy, which, according to the Chinese media and some foreign commentators alike, is abjectly failing.

The outsiders mentioned in this article either declined comment or could not be reached.

These Western sympathizers reflect an old phenomenon of outside elites finding much to like in authoritarian systems—communist, fascist or even Nazi—while downplaying or ignoring their faults. In the 1930s, perhaps the most famous “Friend of China,” left-leaning American journalist Edgar Snow, influenced generations of Americans through his book “Red Star Over China” to view the rising Mao Zedong as a benignly progressive figure rather than a ruthless dictator.

None of today’s friends of China has anything like the fame and prominence of Snow, or others—such as the writers Agnes Smedley and Freda Utley—who had access to the Chinese Communists when they were still seeking power in the 1930s and 1940s. But more recent outsiders perform some of the same role, lending a foreign imprimatur to the Chinese government, by providing quotes and sometimes essays to such state-controlled English-language publications as Global Times or the China Daily, which are then mentioned approvingly in the Chinese press.

Mario Cavolo, an American identified as a senior fellow at the Center for China and Globalization in Beijing—which, according to its website, promotes “Chinese wisdom for the world”—offers a broad defense of China’s governing system. “More and more foreigners living in China are openly stating that they have more true freedom in today’s China than they do in today’s U.S. or European countries,” Cavolo told the Global Times in January.

He has called reports on the Uighur concentration camps “the political hoax of the decade” and claims the BBC has “degenerated into a factory of fake news on China.”

“Who are the lying scum in power sowing hate with their lies toward China?” he asks in one Twitter post. “I'll never give an inch to the reprehensible anti-China crowd.”

A few weeks ago, Global Times broadcast an interview with a French writer, Maxime Vivas, who also described reports of genocide in Xinjiang as “fake news.”

“I want to demonstrate that the Uighur ‘genocide’ claim is a lie,” Vivas said, asserting that he made two state-sponsored trips to Xinjiang in 2016 and 2018. “I revealed the individuals who are the enthusiasts of the lies and their links with the C.I.A.” It’s hard to measure how much influence these modern Friends of China have had on international public opinion. Unlike earlier figures such as Snow, their views must compete with many independent sources of information on China—including most of the mainstream media and human rights organizations—that present a very different, far darker portrait of the country.

But China’s influence operations are far more robust than they were in the 1930s and ’40s. Quoting and publishing such writers is just one of a host of devices China uses to shape foreign opinion, an effort that has been stepped up since Xi Jinping, the country’s paramount leader, became secretary general of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012. These include its Confucius Institutes at foreign universities, its own state-run broadcasting companies aimed at foreign audiences, its efforts to deflect attention from its human rights violations at the United Nations, the China Global Television Network, a state-run television news network available on cable in many countries, and even its use of Twitter, Facebook, and other social media that are, ironically, banned in China itself.

Xi Jinping unveils a plaque at the opening of Australia's first Chinese Medicine Confucius Institute at the RMIT University in Melbourne, on June 20, 2010. William West/AFP/Getty Images

Research institutes, often affiliated with Chinese universities, represent a relatively new instrument of China’s public opinion-influencing arsenal. On their face, such organizations seem similar to genuinely independent non-governmental think tanks in the West. But as a report last year by the National Endowment for Democracy put it, they actually “lend authoritarians an artificial legitimacy” and are “essential tools for propaganda.”

Among these institutes are the Center for China and Globalization, where Cavolo is a senior fellow. Ross is listed as a senior fellow at the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University, which describes itself as “new style think tank with Chinese characteristics” and maintains a global network of fellows, issues reports, and holds conferences on China’s economy, its “Belt and Road” infrastructure projects, and other topics.

The place provided to a small group of foreigners is especially striking now, given that Beijing has not only shut down the BBC but expelled all but a handful of the reporters covering China for independent publications including the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post, even as it has long blocked most of the Chinese-language websites of these publications. The only non-Chinese commentators that residents of China hear about are those like Ross, Vivas, and Cavolo, not well-known in their own countries despite their profiles in China.

It’s easy to dismiss some of these “friends of China” as propagandists, but the more nuanced pro-China commentators make some arguments that are taken seriously by other experts on that nation. Still, they too tend to support the main line in the Chinese press—namely that while China’s situation is extremely bright, the West is in a state of “deepening political decay.”

Perhaps the most prominent is the Canadian-born, Oxford-trained scholar Daniel A. Bell, dean of the School of Political Science and Public Administration at Shandong University and chair of a fellowship program at Beijing’s elite Tsinghua University, financed by the American billionaire Stephen A. Schwarzman. Bell argues in “The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy” (2016, Princeton University Press) that China’s governing system is superior to that of the West in several important ways. Downplaying the nation’s rampant corruption and nepotism, he asserts that leaders and administrators selected by their demonstrated record of achievement, rather than by elections, have helped lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty more effectively than Western-style liberal democracy would have done.

Bell has tempered his enthusiasm for the Chinese model at times with mildly expressed suggestions for change. In an op-ed in the New York Times a few years ago, he was critical of China for its suppression of free speech, though he also expressed a sort of guarded optimism that “things will loosen up eventually.”

So far, things haven’t loosened up at all, even as Bell has continued to portray China in a far more favorable light than most Western experts.

“In my view, the deepest problem is that Western societies prioritize freedom and privacy over social harmony,” Bell said in an interview published by Global Times. “One of the weaknesses of electoral democracies is that it’s often easier to get more voter support by demonizing opponents and inventing enemies rather than reflecting on one’s own responsibility for problems and trying to solve problems in an efficient way.”

Bell’s ideas gain credibility because China is an economic success story. Its ability to realize huge infrastructure projects, for example, stands in sharp contrast to the political paralysis and partisan discord afflicting the United States. But whether China’s success is due to its dictatorial one-party state or in spite of it is debatable, as is his description of China as a “harmonious society” governed by people of Confucian virtuousness.

“New Cold War Will Not Stop US Decline” was the headline of an article last August by Martin Jacques, a British leftist, former editor at Marxism Today, the journal of the British Communist Party, whose main argument was that the United States is fomenting conflict with China in a desperate attempt to maintain is fading global hegemony.

But, Jacques, a senior fellow at another Chinese think tank, the China Institute at Fudan University, predicts that this will fail because “China already holds the upper hand in key respects and, more importantly, is very much on the rise, in contrast to a U.S. in decline.”

Many things can be said about views like Jacques’, Bell’s, and a few others, most conspicuously that they tread very lightly on China’s gross human rights abuses, if they mention them at all. Bell, for example, contends that China is “more harmonious than large democratic countries such as India and the United States.”

But is that true? Columbia University China specialist Andrew Nathan has written a critique of Bell, saying, “China is one of the most conflict-ridden societies on the planet.” According to Nathan, Bell is good at describing the mechanics of China’s “meritocratic” system of government, but he simultaneously exaggerates its benefits and success and the faults of democracies.

“‘The China Model’ is a mix of the empirical and the imaginary,” Nathan has written. “Bell compares the meritocratic system’s potential rather than the actual performance, with the actual performance of liberal democracies.”

When actual performance is taken into account, Nathan argues, China’s leaders seem no more virtuous or capable than democratically elected ones, or else China would not be suffering from a range of problems. These include devastating environmental degradation, deep unhappiness and unrest among its ethnic minorities, not to mention among residents of Hong Kong, as well as widespread corruption, nepotism, and the failure to create any system of accountability that could guard against the abuse of power by its self-selecting, non-elected leaders. A truly “harmonious society” would not be one that forces “re-education” on its ethnic minorities, or locks up the losers of struggles for power, or devotes enormous resources to technology aimed at keeping tabs of its own people.

Nor would a truly “harmonious society” accord senior fellow status to foreigners who praise it while rigorously barring the views of commentators with critical views.

“The Chinese government is surely not a two-party democracy, and yet we can see that China is now the largest, safe, stable and successful society and country on the planet,” Cavolo wrote in an op-ed published in Global Times recently.

Is it? Earlier this year, Teng Biao, a former lawyer from China, wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post calling on Western countries to boycott the Winter Olympics scheduled for China in 2022. Teng was arrested on the streets by plainclothes Beijing police, imprisoned and tortured for two months after he called attention to Chinese human rights abuses in the run-up to the 2008 Olympics, the last time China hosted the Summer Games. He now lives in exile in the United States.

In his op-ed, Teng listed China’s more recent human rights violations, from its crackdown in Hong Kong, the mass incarceration of Uighurs, its pervasive surveillance and censorship of its own citizens, its shutting down of non-governmental organizations, closing of churches, mosques, and Tibetan temples—all part of the tightening of control under Xi Jinping.

It’s a safe bet that, while the “friends of China” are given free rein to praise the Chinese government, Teng Biao’s contrary views will receive no attention at all.