There are many documents in the history of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), but there are only a few so-called “historical resolutions.” That tells the significance of these documents.

The passage of these historical resolutions indicates two major turning points within the CCP—one in 1981 and the other in 2021.

The 1981 historical resolution was the liquidation of Mao Zedong’s line—China’s economy transitioned to communist capitalism.

The ‘Historical Resolution’: A Symbolic Victory

To date, the CCP has adopted three “historical resolutions” since its founding: the 1945 resolution on “certain questions in the CCP history"; the 1981 resolution on “certain questions in the CCP history since the founding of the regime”; and the 2021 resolution on “major achievements and experiences of the CCP’s 100-year history.”These “historical resolutions” are mandates of major changes of leadership within the Party—not the beginning, but the completion of the change—and each one is a “declaration of victory” of the new leadership. The resolution is meant to ensure that all CCP cadres will obey the leader who issued it.

Negating former leaders within the party normally occurs in communist regimes, including in the former Soviet Union. The rejection is not meant to overthrow the party, but to secure the new leader’s authority and his policies in domestic politics, the economy, and international relations.

Objectively, the CCP’s economic turnaround is only a choice between socialism and capitalism.

In its domestic politics, it is a swing between a one-person dictatorship and a collective leadership, and each swing is a consequence of the leadership’s power struggle.

In international relations, it manifests as a form of the CCP’s reorganization of relations with the United States and Russia. The choice for the CCP is either to befriend the United States or to go against it. Its relation with Russia would swing depending on its relation with the United States. For example, during the Korean War, both China and the Soviet Union supported North Korea against South Korea, which was supported by the United States; the China–U.S. diplomatic relation was established when ties between China and Soviet Union deteriorated. Now, the CCP is ready to confront the United States, but the Biden administration is not ready to cut off ties.

The Mao Era Began in the Caves

Under the leadership of Mao, the CCP adopted its first “historical resolution” in 1945 while its members were hiding in the caves of Yan’an in Shaanxi Province.It took place when Chiang Kai-shek was leading the Chinese Nationalists against Japanese invasion. The discussion to end the war against Japan’s military expansion took place in the Cairo Conference between China, the United States, and Britain.

In the name of fighting against the Japanese invasion, the CCP actually engaged in collusion with the invaders in eastern China during World War II.

The CCP followed Moscow’s instruction and passed the “historical resolution.” Mao won the Kremlin’s favor over his Russian-trained comrades. The resolution didn’t seem to affect China as a whole.

The CCP considers the resolution a turning point in its history—Mao claimed his leadership, even though it took place when he and his bandits were hiding in the caves while plotting to take down the Nationalists.

In 1949, when the CCP won the civil war with the arms support of the Soviet Union and the leanings of several pro-communist American diplomats, China entered the Mao era—in other words, the “Mao Disaster.”

Mao’s policies created major disasters that harmed China, even to this day, and more so to the world today.

Mao’s theory of rebellion during the Cultural Revolution appealed to many radical leftist youths in the United States and Europe. These Mao fans influenced Western civilization through generations, leading to the subsequent far-left extremism in the Western countries today.

After Mao’s death, his planned economy and state ownership—which led to the total destruction of the Chinese economy—was disguised as a market economy. However, his socialist/communist influence continues in the West.

Liquidating Mao’s Line, Stepping Into Communist Capitalism

The CCP passed its second “historical resolution” in 1981 to confirm a political change within the Party.After Mao’s death in 1976, Hua Guofeng, his designated successor, failed in the political struggle; Mao’s followers were expelled by veteran cadres who wanted to regain their power.

The 1981 “historical resolution” was seen as a victory in liquidating Mao’s political line and his policies. The CCP walked out of the Mao era and entered the Deng, Jiang, and Hu era—which I call the Communist Party’s capitalism.

The CCP uses the capitalist system to strengthen its authoritarian regime, and this, in turn, becomes its own demise.

Since the reform and opening up, the Communist Party’s capitalism went through three historical stages.

The first stage was from 1997 to 2002, when a large number of CCP officials became capitalists during the full privatization of state-owned enterprises.

The second stage occurred between 2002 and 2013. Communist businessmen accumulated massive assets through corruption and allocated them overseas. They worked very hard to hollow out the regime.

The third stage was from 2013 to 2021. After Xi came to power, he realized the economy was almost empty, nearly all officials’ families had gained their foreign citizenships, and the CCP’s legitimacy was at stake.

The CCP Is Digging Its Own Grave

Karl Marx made two major mistakes, which allowed the CCP to make its significant historical contributions to correct Marxism.Marx’s first mistake was that he believed there were only two and complete opposite roads in the world: socialism and capitalism. In fact, the CCP’s history proved that it has the ability to graft the two systems to make communist capitalism. I don’t believe Marx would appreciate the CCP’s innovation.

His second mistake was that he believed the Communist Party is the gravedigger of capitalism, and socialism will replace capitalism. However, the CCP completely subverted his theory.

The corrupt cadres’ actions prove that the communist capitalists favor U.S. capitalism over China’s socialism. They are definitely not the gravediggers of capitalism; on the contrary, they are digging a trap that will ruin the communist regime.

The corrupt officials have harvested their wealth and future through money laundering, buying overseas properties, and applying for U.S. green cards. They nearly hollowed out the regime before Xi started his anti-corruption campaign in 2013. They don’t hold grudges against the communist autocratic system, but they do embrace U.S. capitalism for fear of being liquidated.

Can Xi Save the CCP by Liquidating His Predecessors?

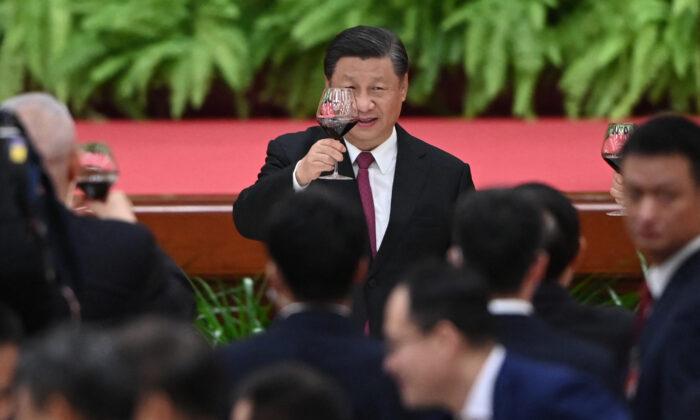

The third “historical resolution” is definitely the outcome of another political turnaround, which marks the beginning of the Xi Jinping era.When Xi first came to power, he was facing pressure from various high-level factions from the Jiang Zemin era. In particular, there was discontent, disobedience, and even rebelliousness in the army, police, and secret service in the Ministry of State Security. Xi took several years to reform the entire military command system, cleanse the public security sector through a nationwide crackdown on corruption, and finally seize power.

A decade of crackdown finally had veteran cadres from the Deng, Jiang, and Hu era kowtow to Xi, and the Party swung back to a one-man dictatorship. Xi is the new dictator—China and the CCP have officially entered the Xi era.

Xi still needs to secure his long-standing dictatorship through various policies.

In politics, he will play down criticism of Mao’s mistakes, remove officials from the political factions of Deng, Jiang, and Hu, and strengthen the one-man rule as Mao did.

Amid the economic downturn, Xi seeks to tighten control over private industries and mobilize all economic sources, with the objectives of slowing economic decline and preparing for wars and arms expansion.

What about the gravediggers? Have they disappeared? Mao once said, “The enemy is in the Party.” They might be restricted from leaving China, they might play submissive, but they are waiting for their chance to make a move, which could either be a coup or an assassination.

Will Xi Save the CCP?

After all, Marx has fooled them all. The CCP seized power under the banner of the proletariat, but none of the Party cadres are willing to stay as a proletariat—they'd rather remain in the property-owning or capitalist class. But apart from emptying out the communist regime, they don’t have any other way to quickly accumulate wealth.Consequently, the corruption would only lead to the demise of the regime. No one will be able to prevent the collapse of the CCP, and neither can Xi avoid his destiny as the last dictator of the regime.