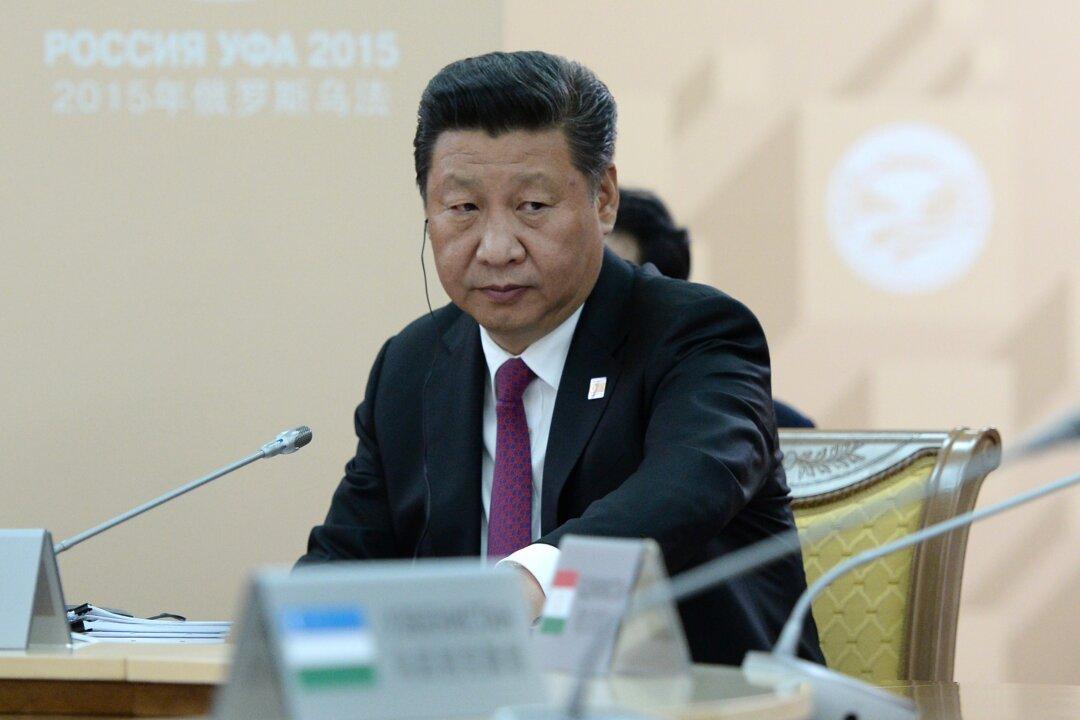

For the last two years, Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping has been working relentlessly to dismantle the political network that had previously controlled China. That group’s power is now effectively broken—though observers are still waiting for the final nails in the coffin.

The fruits of this cleansing of the ranks were trumpeted by Xinhua after the Communist Party’s fourth plenary session in October. The state news mouthpiece published a list of “55 ‘Big Tigers’ That Have Been Purged.” For observers of Chinese communist politics, it was no surprise that a large chunk of those men shared the same political patron: Jiang Zemin.