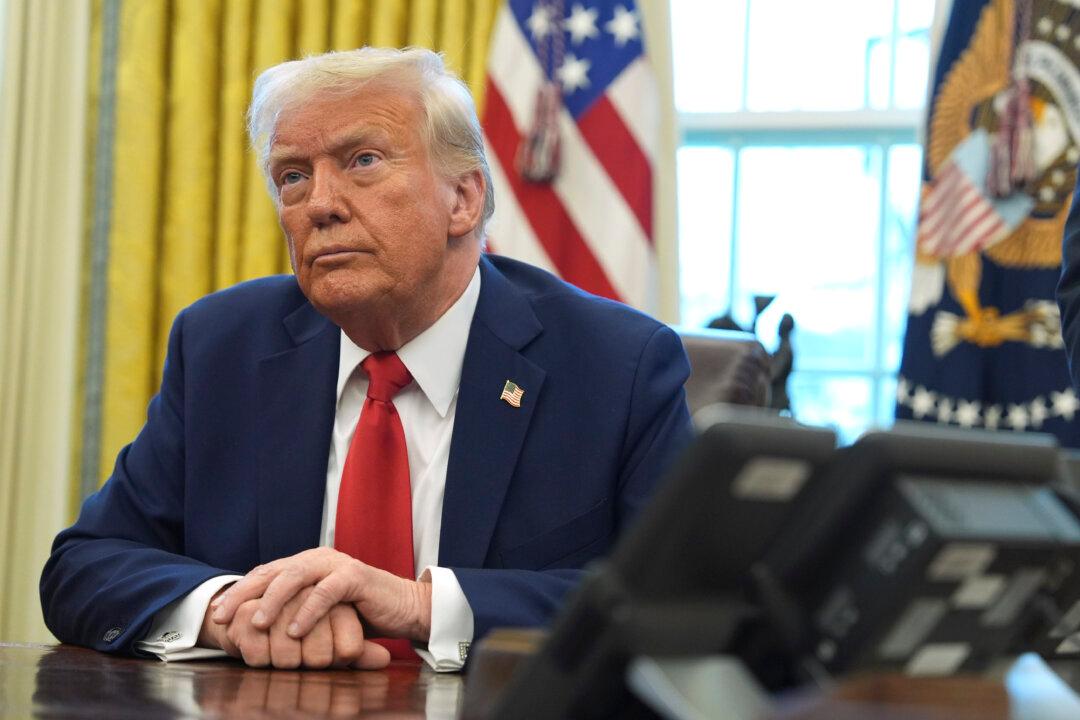

President Donald Trump’s recent ban on Chinese social media apps TikTok and WeChat is aimed at blocking Beijing’s access to large volumes of U.S. personal data that could be used for operations to subvert the United States, a top Justice Department official said on Aug. 12.

Trump last week issued executive orders banning transactions with the Chinese owners of TikTok and WeChat apps, tech giants ByteDance and Tencent Holdings, respectively, on national security grounds. The ban is due to take effect in September.