PRAGUE—One day, an artist from central Europe heard a news story about Chinese prisoners of conscience being used as living donors for organ transplants—without their consent. After her own research, she uncovered reports of abuse in China that inspired her to create a unique artistic project that has drawn international attention.

“When I heard about this issue in a Czech Radio broadcast in 2015, I started looking for more information,” says Czech artist Barbora Balkova, a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague.

“The fact that some people are locked up in prison and then serve as a living organ bank was really overwhelming information for me. My first inclination was not to believe it, but then I started to learn about the details from sources at home and abroad, and that became a strong impetus for the panda project,” the artist said. “As soon as I heard about it, I knew I wanted to react.”

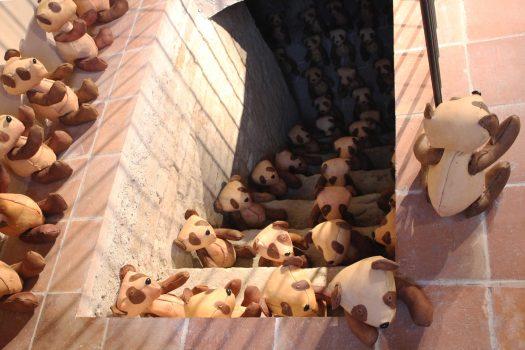

Wanting to attract attention and raise consciousness about China’s large-scale system of involuntary organ harvesting, she decided to use the panda bear for her new project.

Making the Bears

“For the production of panda bears, I used an imitation of human skin made of silicone.” Silicone used as skin is a powerful visual medium used to tell the viewer that the artist is talking about living human sacrifices. “I’ve shown the pandas as a very positive and well-known Chinese symbol, but in a totally different context, one which the Chinese regime is trying to conceal.”The fact that the bears’ bodies are made of imitation human skin indicates that something is not entirely right. The artist uses obvious cuttings and stitchings on each panda to symbolize the transplant surgery abuse.

Getting Attention

Her exhibition drew the attention of Chinese surgeon Enver Tohti, one of the few to give direct testimony on how he personally carried out an organ transplant from a prisoner in China who was still alive. He was commanded to do so by his chief physician, so he had hoped that everything was “legal” and “ethical.”

“When you live in a communist regime such as China, you can’t think independently. You have to follow orders,” Tohti said in his testimony to the British Parliament in 2015.

After spending years in England, he realized he had committed a crime. Then, like artist Barbora Balkova, he learned that the abuse of prisoners for transplants in China is widespread, and that his experience was only one of a thousand others. In 2014, he stepped out to publicly testify about what he had personally witnessed. He met with the artist and her pandas in Prague in 2017.

Through Tohti and Matas, the story of Balkova’s panda bears came to England. From there, it traveled through Ms. Yukari Werrell, the manager of the Japan Initiative at The International Coalition to End Transplant Abuse in China, to Japan.

The Japanese SMG initiative originated in the Chamber of Governors of Japan at the beginning of 2018. Since then, its work has been supported by 26 national and 28 prefectural councils. The chairman of the initiative is a Japanese journalist and human rights expert on China, Hataru Nomura.

“What is happening today in China seems to me to be a parallel to what was happening during the Second World War in Europe in Nazi Germany,” Balkova said. “I always wonder how it was possible that it was happening, and that the world did not stand up against it,” she said. “No one wanted to believe it. Only after the concentration camps had opened were the shocking atrocities shown.”

“I don’t know what further evidence will be needed to change things fundamentally, as a result of public pressure or diplomatic ties,” Balkova said.

“I would definitely be happy if my project could contribute to a wider awareness that hundreds of thousands of people are dying in China just [so someone can profit from] their organs,” she said. The artist intends to continue creating the bears, as she says, until “organ harvesting in Chinese prisons definitively ends.”