Commentary

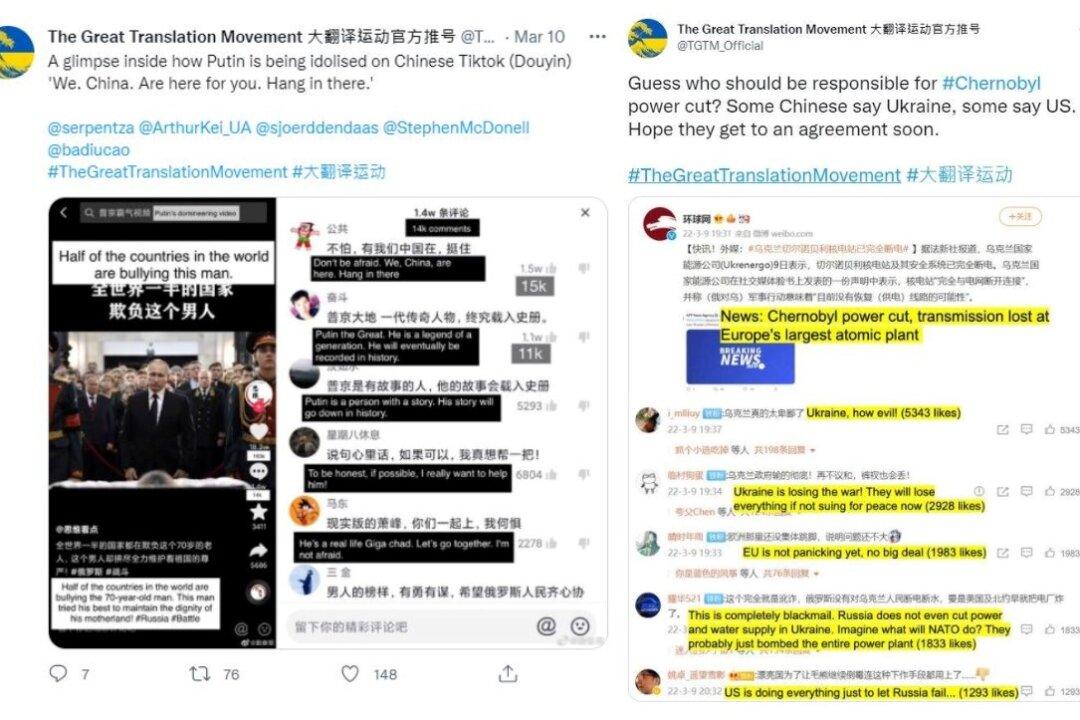

While Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has seen economic repercussions around the world, from supply chain disruption and to shortages in daily goods like cooking oil and tomatoes in Europe, the impact in China is more ideological.

While Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has seen economic repercussions around the world, from supply chain disruption and to shortages in daily goods like cooking oil and tomatoes in Europe, the impact in China is more ideological.