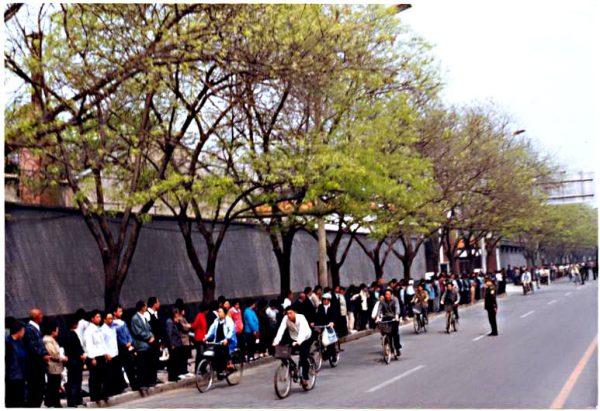

NEW YORK—Sixteen years ago, Beijing resident Li Kai joined over 10,000 other ordinary Chinese on their way to the center of the capital. They calmly gathered on Fuyou Street, the location of China’s Central Appeals Office—and right next to Zhongnanhai, the seat of China’s regime and living quarters for the Communist Party leadership.

It was the morning of April 25, 1999. The people that gathered for the appeal were practitioners of Falun Gong, a popular Chinese spiritual discipline introduced to the public in 1992.

Despite Falun Gong’s positive reception among the Chinese populace, of whom an estimated 70 million–100 million had taken up the practice in just 6 years, practitioners were now the targets of an increasingly belligerent and paranoid Communist regime.

Li Kai began practicing Falun Gong in 1997. On the April 23, over 40 Falun Gong practitioners had been beaten and detained by authorities in Tianjin, a major city 90 miles south of Beijing.

There had been other instances of officials harassing Falun Gong, but when the practitioners in Tianjin sought to get those detained out of jail, the stakes were suddenly raised. The practitioners were told to take their case to Beijing.

And appeal they did. The gathering was spontaneous—Li, speaking to Epoch Times, found out about the event early on the morning of April 25, when he went to his usual meditation site in Beijing and found it unusually empty.

The word about what had happened in Tianjin had spread from person to person, and thousands of practitioners from Beijing and other parts of the country traveled to the Appeals Office. Police seemed to be waiting for them and directed them to the sidewalks ringing Zhongnanhai.

Premier Zhu Rongji came out of the Zhongnanhai compound to greet the demonstrators. After a round of courteous negotiations between the premier and several practitioners, the crowd dispersed as quietly as it had formed.

On Fuyou Street, where the famous “Tank Man” had been photographed nearly 10 years prior during the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, it seemed that the Chinese regime and people had reached a peaceful conclusion.

As the practitioners wended their way home, they might have imagined that a crisis with the regime had been averted. In fact, the start of a bloody and, as of today, still ongoing persecution would begin in three months.

For Li, that persecution would mean 10 years in prison. For Falun Gong, it would mean tens of thousands of deaths in the custody of police and hospital personnel. For the Communist Party of China, it was a point of no return.

A Means to Persecution

Even as Premier Zhu reassured Falun Gong practitioners that the regime was not against Falun Gong and noted the constitutionally protected freedom of belief, China was on the brink of a new Communist terror campaign, the likes of which had not been seen since the Cultural Revolution.Jiang Zemin, who was at the time general secretary of the Communist Party, used the events of April 25 to “prove” that Falun Gong was both organized and an immediate political threat. According to sources inside the Party, Jiang berated Zhu for being soft on Falun Gong.

In a letter to the Communist Party Politburo penned the night of the demonstration and openly published in 2006, Jiang described Falun Gong as nationwide religious organization with a worldview inimical to that of communism and Marxism.

Jiang further claimed that Falun Gong had overseas connection, and was to be handled with “effective measures to prevent similar things from happening again.”

In fact, according to Falun Gong practitioners, the practice was never an organization, as it has neither hierarchy nor any lists of members.

On June 10, an extra-constitutional Party unit was created to oversee the coming eradication campaign. This group, named for its founding date, came to be known as the 610 Office. It operates above the law and at all levels of administration.

“I refuse to believe that I cannot eradicate Falun Gong,” Jiang Zemin said, according to anonymous internal sources in the Communist Party.

On July 20, 1999, the persecution of Falun Gong began. Practitioners around China were rounded up into sports stadiums, and state media ran an unending propaganda campaign demonizing the practice and its teachings. Investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann estimated in 2010 that between 400,000 and a million practitioners were being held at any time in prisons, detention centers, unofficial “black jails,” and labor camps across the country.

The repression continues to the present day and is shrouded in secrecy. While Minghui.org, a website run by overseas Falun Gong practitioners that documents the persecution, has been able to verify the deaths of over 3,800 due to torture and abuse at the hands of Chinese regime authorities, the true number is far higher.

Throne of Corruption

Jiang Zemin’s campaign against Falun Gong was meant to be a quick affair, through which Jiang hoped to expand state control and entrench his own authority. The persecution itself was not popular—in an age where China had embraced market economics, the Marxist ideology of historical materialism was not in vogue, and furthermore, Falun Gong was widespread even among Party members and their families.To support the persecution signaled loyalty to Jiang Zemin’s personal authority. Thus, countless officials elevated to high positions in the security and legal sectors, as well as the military, were those who had made clear their intention to follow Jiang.

Zhou Yongkang, former head of the Communist Party’s internal security forces, performed key roles in persecuting Falun Gong practitioners. Bo Xilai, a charismatic Politburo member, ran a major organ harvesting operation while serving as the provincial head of Liaoning Province in northeastern China.

Jiang also promoted many of his cronies to high military posts, such as Xu Caihou, who, despite never having served in a combat unit, became the second most powerful man in the People’s Liberation Army.

No Peace on the Red Stage

Meanwhile, Falun Gong proved impossible to crush. According to Minghui estimates, there are over 20 million dedicated practitioners in China who disseminate Falun Gong materials and, starting in late 2004, the “Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party,” an editorial series published by Epoch Times.The “Nine Commentaries,” which provides a critical look at the history and nature of the Chinese Communist Party, immediately caught on among the Chinese people and sparked the Tuidang Movement—“Tuidang” means “quit the Party.”

By 2009, 60 million people had announced through the Tuidang Center website their renunciations of the Communist Party and its affiliated youth organizations, of which the vast majority of Chinese were members at some point in their lives.

The turning point for Jiang and his henchmen came in 2012, on the eve of the rise of new regime head Xi Jinping. The defection of Wang Lijun, Bo Xilai’s chief of police, to the American Consulate in the city of Chengdu that February tipped off the Party center. Bo and Zhou Yongkang, it turned out, had plotted together to undermine Xi’s upcoming administration. Details of a possible coup attempt were leaked.

Xi, unlike many of the officials promoted by Jiang, played no direct role in the persecution of Falun Gong.

As events would show, Bo and Zhou’s plots, whatever the details, did not come to fruition. Bo was put on trial and received a commuted death sentence.

The trial of Bo was a prominent moment in the wide-ranging anti-corruption campaign, still continuing today, that has targeted Jiang loyalists. It has felled scores of top Communist officials and Chinese businessmen.

The Echo of April 25

The 10,000 Falun Gong practitioners who stood up for their faith on April 25, 1999, set a precedent for the rest of China. Following the peaceful demonstration at Zhongnanhai, the nonviolent demeanor that practitioners would maintain for the coming 16 years of persecution has tremendously affected the general population as Chinese people re-evaluate how they look at themselves and society.China finds itself amid crises on all fronts, be they in the form of factional struggle within the regime, skyrocketing government debt, failing real estate and industrial projects, or a dearth of clean air and water. Capital flight has bled the country of trillions of yuan over the last decade as wealthy Chinese escape for foreign havens.

The persecution of Falun Gong is a product not just of the Jiang regime, nor is it any simple blunder of misunderstanding by the regime. Rather, it arose from one of the defining characteristics of the Communist Party—the thirst for control. The Communist Party is not bound by any Chinese law, a situation that has persisted throughout the six-decade existence of the People’s Republic of China.

Despite 16 years of persecution, developments in China show that the practitioners of Falun Gong are not alone. As of April 14, 200 million Chinese have renounced the Chinese Communist Party and its affiliated organizations.

After the persecution began, Li Kai, who took part in the April 25 appeal and now lives in the United States, continued to support Falun Gong publically. He was arrested in 2002 and eventually served 10 years in prison.

“[The demonstration on] April 25 was legal and rational,” Li said. “It was a stand on the side of justice.”