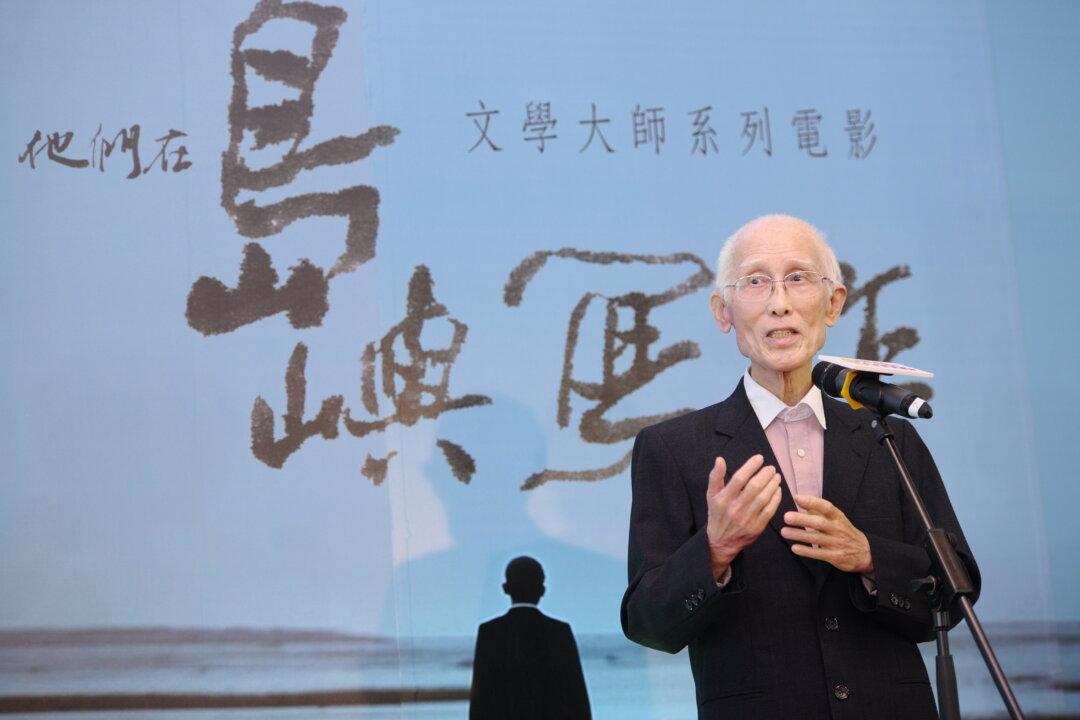

Hong Kong has a colonial history of over a hundred years, during which it established itself as a confluence of Eastern and Western cultures and has been inextricably linked with the footsteps of many literati. In 1974, Taiwanese poet Yu Kwang-chung came to Hong Kong for his teaching career and authored the poem “Let’s Just Call It Home.” He spent the next 11 years in Hong Kong, which coincided with his creative prime, and his inhabitance among the Sha Tin hills became the most enjoyable part of his life.

The end of 1984 witnessed the signing of the Joint Declaration between the then-Chinese and British governments as a settlement on the future of Hong Kong. The following year, Mr. Yu left Hong Kong and returned to Taiwan. In his farewell to Hong Kong, he wrote affectionately, “I’m afraid that this green land (Hong Kong) will become deeply embedded in my dreams” and “I suddenly realized that this is a dreamland lost.” Why did Mr. Yu feel this way? What happened in Hong Kong that created such a deep feeling in him?