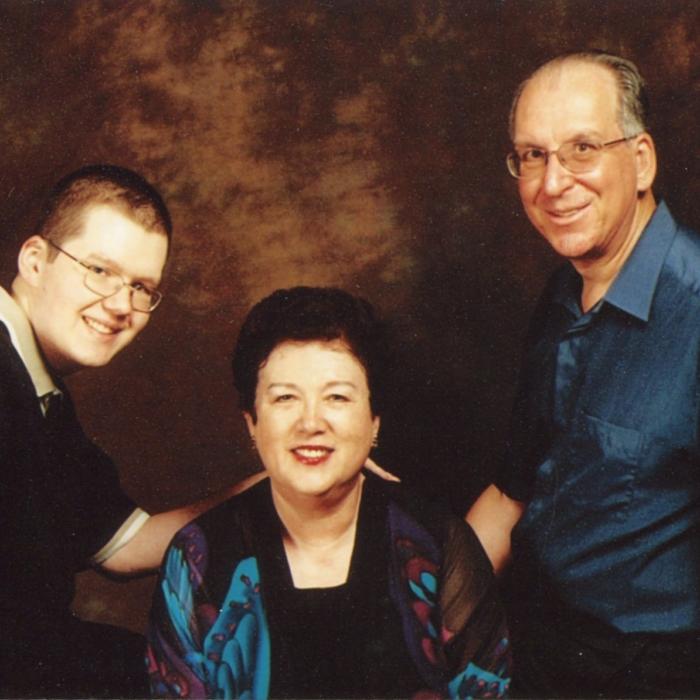

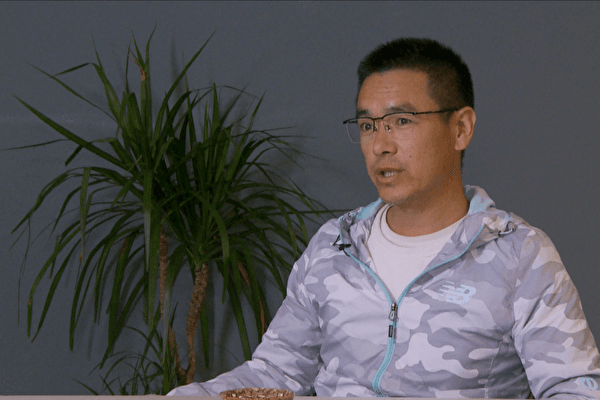

Over the past several years, Chinese dissident Chen Siming became known for steadfastly observing the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre memorial. His actions and social media posts led to arrests, travel restrictions, and constant attention by police, particularly around the June 4 anniversary of the massacre. Finally, last summer, after escalated threats and harassment, he decided to try to escape China.

Run!

Things came to a head for the activist on July 21, 2023. At the time, the 60-year-old Mr. Chen was living in Zhuzhou, in southern China’s Hunan province. The Zhuzhou police summoned him that morning and told him he was about to be subjected to a psychiatric evaluation.To Mr. Chen, the threat of being locked in a psychiatric institution was more frightening than prison.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is notorious for using its psychiatric institutions to silence dissidents. They allow the CCP to completely remove activists from the justice system, with no hope of a trial, while diagnosing them with mental illness so they are socially isolated even after release. Inside China’s mental institutions, victims are subject to mental and physical abuse. After they return home, many of them deal with PTSD and even early dementia from being forcibly medicated.

The Escape

Mr. Chen hastily grabbed his phone and power bank. Avoiding even a backpack, he bundled two sets of clothes in a white plastic bag and started off on his electric scooter. A blend of excitement and fear pulsed through his veins.After weaving through a few residential areas and making various turns, he headed toward the main road. There, in a bold move to minimize being followed, he drove against oncoming traffic, confronting the rushing vehicles.

In an hour, he reached a long-distance bus station. Glancing left and right, he confirmed that no one was tailing him. Swiftly discarding the scooter, he boarded a bus bound for Changsha, around 45 miles north of Zhuzhou. Upon arrival, he promptly switched to a subway heading for Huanghua Airport.

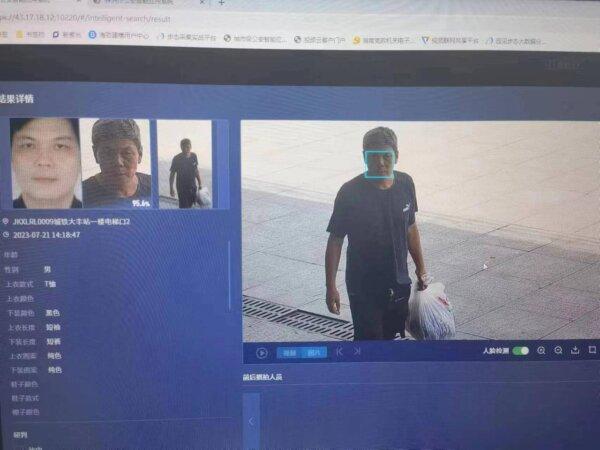

The usual travel time from Zhuzhou to the airport is 50 minutes. That day, it took Mr. Chen five and a half hours. He knew that the police had been monitoring him through his ID since 2018, and any swipe of an ID at a checkpoint for public transportation would raise an alarm. Despite the detour, he knew that long-distance buses and the subway were the only two means that would allow him to avoid checkpoints because they didn’t require an ID swipe.

It was 5:30 p.m when he reached Huanghua, and there were very few passengers in the airport. The earliest flight to Xishuangbanna, Yunnan province—a prefecture bordering Laos—was at 8:30 a.m. the following day.

Looking Back on Activism and Intimidation

Since he began publicly speaking out in 2016, Mr. Chen had been repeatedly summoned by local police in the name of “discussion,” “having tea,” and “travel.” Courtesy calls, and at times, detention, had become part of his everyday life. Around June 4, local police would invariably track him down and restrict his freedom, in the name of preventing him from “disrupting social order.”Prior to the Tiananmen Square anniversary last year, local police called Mr. Chen and informed him he would be taking a “trip.”

Thinking quickly, he tweeted a post about the massacre before police could arrive. The police noticed the post and insisted he delete it. Mr. Chen refused. Consequently, he was jailed for 15 days.

On the morning of July 21, the police summoned him and again asked him to delete his post. Mr. Chen agreed, under the condition that the police provide him with proof of detention and summons. The police rudely rejected his request.

“Old Chen, you can serve a 3 to 5-year sentence, or you can go to a mental hospital. Do you know that I can arrange a psychiatric evaluation for you right away?” The officer spoke methodically but with an intimidating tone.

The threat reminded Mr. Chen of Dong Yaoqiong, a young woman from Zhuzhou who had splashed ink on a poster of Chinese leader Xi Jinping. She had been forcibly committed to a psychiatric facility; her father, who had advocated for her, had been sent to prison, where he had died.

“Run,” had crossed Mr. Chen’s mind several years ago when friends encouraged him to leave China. He had hesitated because he wanted to continue his activism. Moreover, he feared risks caused by the language barrier and his lack of a valid passport, which had been canceled by the police in 2019. He knew he would only be able to leave China by crossing the border illegally.

Despite his fears, he was now on the path of escape. With everything at stake, he could only press on.

Crossing the Border

At 10:30 a.m. on July 22, Mr. Chen’s plane landed in Xishuangbanna. He was still highly nervous: on the plane he had fretted that police were in neighboring seats, or that they would be waiting for him at the airport exit.Luckily, it appeared the Zhuzhou police were still unaware of his escape, and he left the airport easily. He felt more relaxed now and realized he was hungry. He hadn’t eaten anything since the morning before. He located a market, quickly ate, bought four bottles of water, and headed toward the border.

To evade police tracking, he continuously switched vehicles—taking taxis, motorcycles, and private cars.

Finally, at 4 p.m., in the cool afternoon of a Yunnan summer, he reached the border foothills.

Looking up, he couldn’t see the peak of the steep mountain he was facing. A stream flowed, and some birds chirped and fluttered among the trees. Mr. Chen, however, had no interest in scenery. This was the border, where one could encounter military patrols at any time, not to mention the possibility of a police pursuit from behind. He dared not linger. He quickly began to climb.

The mountain path became increasingly steep, and he felt more and more tired. To lighten the load, he discarded the four bottles of water and tossed away the clothes he carried.

Finally reaching the top, he breathed a sigh of relief, thinking he had reached the border. Then, another peak emerged, still far from the border. He had no choice but to gather his strength and continue the journey.

Weather in mountainous areas changes rapidly. Moments ago, the sun had been shining, but suddenly a torrential downpour began. It left Mr. Chen soaking wet and facing a challenging journey on the wet and slippery mountain road.

Upon reaching the top of the second peak, he was exhausted. He threw away the power bank, keeping only his phone and charger—his sole means of communication, something he couldn’t afford to discard.

Finally reaching the mountaintop, he once again believed he had reached the border. To his dismay, another peak lay ahead.

At this point, he realized that the challenge was no longer the language barrier, or the myriad other things that had caused him anxiety. It was simply the peaks looming before his eyes.

When he came to the fourth peak, his strength was challenged to its limit, and each step became extremely difficult. He was panting, covered in sweat, almost on the verge of fainting. He began to question whether this risky venture was worth it. He thought about giving up.

However, the thought was soon dismissed. He did not want to relive the past.

Since 2016, he had been a target of police harassment: daily police phone calls, arrests, and frequent detention.

“China is tainted by evil, where life lacks dignity,” Mr. Chen reflected. He knew there was no turning back. Taking a daring leap might be his only chance for a way out. He clenched his teeth and kept climbing.

The Risky Downhill

Night was setting in, and a few bird calls still echoed. Mr. Chen’s relief at reaching the border was swiftly replaced by a new fear: he could be apprehended by Laotian border security at any moment. China has a great deal of influence in Laos, and getting caught would mean a return to China.He refrained from contemplating further. The urgent task was to get down the mountain.

On the dark mountain, he couldn’t see his hand in front of his face. To avoid detection, Mr. Chen didn’t even use his phone’s flashlight, relying only on the screen’s faint glow to illuminate the barely distinguishable path. He moved forward gingerly, feeling his way with each step as he carefully navigated.

Suddenly, he slipped. He lost track of time as he rolled down the slope. He was finally stopped by a large tree. After a long and painful pause, he regained his composure and slowly climbed back to the trail.

After walking for a short distance, however, he slipped and tumbled down the hillside again.

The cycle continued—taking steps, rolling down, taking more steps, rolling down again. He lost track of how many times he had fallen. Arms, legs, and feet were wounded by branches and thorns. His body was covered with blood, rain, and mud.

At this point, he lost his sense of fear. Surviving was his only thought.

“Boom!” His head slammed into a hard object. Unable to see, he had hit a large tree in the path. A lump rose on his forehead. His two front teeth were chipped.

In this manner, he tumbled, rose, tumbled, rose again. Eventually, at 10 p.m., he reached the mountain’s base. He dared not pause to rest. He headed straight for the Golden Triangle: a lawless, quasi-autonomous region where the borders of Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar meet.

Hiding Out in the Golden Triangle

The Golden Triangle is a gambling and tourism hub catering to the Chinese; it has been called a “de facto Chinese colony.” Crime is rampant: drugs, gambling, money laundering, human trafficking, scamming, and wildlife trafficking. The special economic zone has a private police force; Laotian police reportedly need special permission to enter.Mr. Chen found a secluded hotel and holed up there. He kept his window covered and spent his days inside the small room.

On July 26, he received a message from a friend: the police had gotten his information from the airline and initiated a large-scale manhunt.

Overcome by fear, he promptly cut off communication with his friends in China. He knew that he must leave Laos quickly, but was unsure about his next steps.

On July 29, he read a news report that human rights lawyer Lu Siwei, who had escaped from China, had been captured by Laotian police as he was about to board a train to Thailand. The Laotian police would almost certainly send Mr. Lu back to China.

The report compounded his sense of urgency.

By Boat to Thailand

Back in the hotel, the days felt unbearably long. Finally, however, an opportunity presented itself. Mr. Chen boarded a local fisherman’s boat late one night. The narrow boat was just a bit wider than his body. He lay face down in the waterlogged bottom of the craft as it sailed through the dark night.After about half an hour, the boat reached the shore. He climbed ashore and crossed a field of waist-deep grass to a road. Then he headed straight for the hilly, forested Golden Triangle region of Thailand, and then on to Bangkok.

In Bangkok, Mr. Chen knew he was safer, but not safe. Although Thailand is not as tightly controlled by China as Laos, the two countries maintain close ties. If caught by the police, he could be detained and secretly handed over to Chinese authorities.

He found an apartment, going out only to buy food. When he did, he acted like a thief, glancing over his shoulder lest he was being followed. His constant fear once again made the days seem like an eternity.

Gradually, he came to know a few Chinese in the Thai refugee community. Some were awaiting resettlement by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Others were planning to make the risky trip to the United States through the jungles of South and Central America.

The clandestine route had emerged as a choice for many who left China in desperation after years of zero-COVID measures. They flew from Thailand to Istanbul, Turkey, then took a flight to Quito, Ecuador. Then they would proceed north, passing through Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico before crossing the California border.

Mr. Chen considered this idea but discarded it. His experience along the China–Laos border had convinced him that this route could cost him his life. He also discovered that, since mid-2023, the CCP had collaborated with Thailand to intercept Chinese at Thai airports. More than 80 percent of Chinese passengers from Bangkok to Istanbul found themselves unable to board the plane. Once intercepted, their expensive plane tickets were null and void.

Refugee Status

One day, someone in the refugee community advised him to register with the UNHCR, suggesting that it might be a chance to enter another country legally. On Aug. 18, Mr. Chen applied for refugee status, using several old news articles about himself as supporting material. He didn’t hold out much hope for success. He knew that some people who had registered with the UNHCR had been waiting for years without positive outcomes.Despite his pessimism, on Aug. 25, Mr. Chen received word from UNHCR, scheduling an interview for Aug. 30. Unexpectedly, on the day of the interview, the UNHCR granted him refugee status.

Mr. Chen was ecstatic. With his refugee status, he wouldn’t face deportation to China, and he could legally reside in Thailand.

After the anxious weeks, he breathed a sigh of relief. He wanted to take some time for himself, explore tourist sites in Thailand, and indulge in the country’s street food delights.

Unfortunately, while he was enjoying himself, a piece of information crashed down on him like a bucket of cold water. The Chinese police were aware that he was in Thailand. In submitting his documentation to the UNHCR, he had also unwittingly revealed his identity to CCP informants.

Mr. Chen was once again in the depths. Staying in Thailand was no longer feasible.

Thankfully, his refugee status gave him freedom to move about. He returned to Laos first, believing that the CCP might not anticipate this move, and then back to Thailand. He traveled back and forth a few times. However, this was not a sustainable solution; he needed to leave Thailand for good.

A Detour to Taiwan

On Sept. 22, Mr. Chen bought a plane ticket. Because he didn’t have visas to travel elsewhere, the ticket was—paradoxically—for a flight back to China. However, the trip from Bangkok to Guangzhou included a plane change in Taiwan.The flight landed at Taiwan’s Taiyuan Airport at 6:30 a.m.Soon he was expected to be on the flight to Guangzhou.

Upon disembarking, he promptly recorded a video and shared it on social media, asking for assistance from the international community, and appealing to Taiwanese authorities not to repatriate him to China.

Suddenly, he found himself thrust into the international spotlight. Media rushed to cover the story, and his phone rang with one interview request after another. Local human rights organizations, grassroots groups, and human rights activists from around the world mobilized to rescue him.

At 2:00 p.m. that afternoon, Mr. Chen was brought to the office of Taiwan’s Immigration Agency for questioning. As the three-hour conversation unfolded, the atmosphere was volatile. However, immigration officials finally grasped a broad understanding of his situation, and the atmosphere became amicable.

At the same time, civic organizations and human rights groups in Taiwan were actively mobilizing to secure housing for Mr. Chen during his stay there. Activists from Canada and the United States were also reaching out to their respective governments. On Sept. 26, Canadian activist Sheng Xue submitted Mr. Chen’s information to the Canadian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, facilitating a video call with Canada’s Foreign Minister.

He was starting to breathe easier. However, he still grappled with feelings of confusion and anxiety.

On the afternoon of Oct. 2, officials from the immigration agency met with Mr. Chen, along with a Canadian diplomat. The diplomat, in fluent Mandarin, said, “We are organizing your journey to Canada and booking your flight. You may have to wait for about a week.”

He suddenly grasped his situation: He had been accepted by Canada. It was as if he were emerging from a nightmare. The life-and-death saga of the past two months had finally reached its conclusion.

Overcome by emotion, Mr. Chen wanted to hug the Canadian diplomat. Then he became aware of his long hair, scruffy beard, and rumpled attire of t-shirt and shorts. Abashed, he simply said over and over, “Thank you, thank you, thank you.”

Epilogue

As the international community rallied to rescue Mr. Chen during his days in the airport, the CCP was also busy.Chinese police apprehended and questioned anyone who had connections with Mr. Chen or had offered assistance to him. Some faced prison.

The CCP’s efforts didn’t stop after Mr. Chen reached Canada. Three months later, the Hunan police delivered a message, urging him to keep silent, “so as not to end up like Hua Yong.”

Hua Yong was an artist who escaped China only to drown mysteriously in Vancouver.

Mr. Chen did not succumb to CCP intimidation. During his journey, he had received assistance and support from a multitude of individuals, most of whom he had never met. He owed a debt of immense gratitude to these anonymous friends, he told The Epoch Times. They had enabled him to reach freedom. He owed it to them to continue to speak out.