News analysis

Last year, the Chinese Communist Party announced that among other reforms, it would be dissolving the 610 Office, an executive “leading group” that has played a key role in the ongoing persecution of Falun Gong, a traditional Chinese spiritual practice.

The 610 Office is the informal name of the Central Leading Group on Dealing with Falun Gong created on June 10, 1999, in anticipation of the persecution, which began on July 20. Following the expansion of its tasks to cover other faith groups, it was re-christened the Central Leading Group for Dealing With Heretical Religions.

On March 21, 2018, the CCP announced a series of structural reforms planned for Party and state bodies that further concentrate power in the hands of the central Party authorities under China’s current leader Xi Jinping. Among the 60-item list of changes was that the 610 Office would be disbanded, as well as two other organizations related to the anti-Falun Gong campaign.

Viewed in isolation, the move comes across as a technicality. The Communist Party has maintained its hardline attitude towards Falun Gong since the beginning of the persecution in 1999—as the ongoing arrests, harassment, and secret trials of Falun Gong practitioners can attest to. And under Xi’s watch, the CCP has only turned up the dial on its other human rights abuses.

But when placed in the broader context of Chinese regime politics, the decline and end of the 610 Office reflects the intensity of factional struggle in the CCP. It also adds to a long list of indicators that while the Party cannot afford to stop persecuting Falun Gong, the campaign has become an awkward practical liability for it and its leaders.

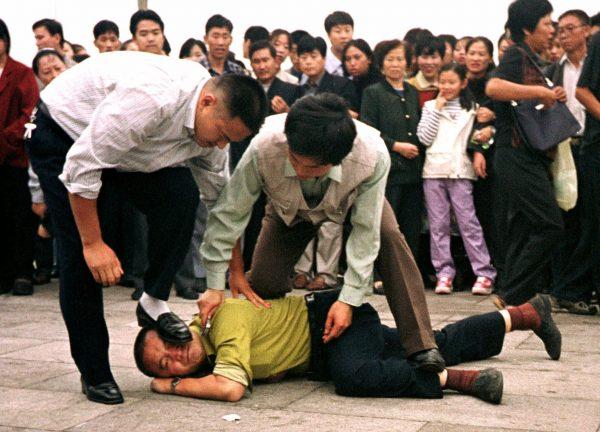

Police detain a Falun Gong practitioner on Tiananmen Square as a crowd gathers around in Beijing on Oct. 1, 2000. AP Photo/Chien-min Chung

Politics of Persecution

Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, is a traditional Chinese spiritual discipline practiced by tens of millions of people. Its adherents have been subject to violent suppression by the communist authorities since July 1999. Thousands of Falun Gong practitioners are confirmed to have died from mistreatment in custody. Meanwhile, deepening investigations suggest that even larger numbers of people have been outright murdered for the harvest and sale of their organs.The persecution of Falun Gong was ordered by then-Party leader Jiang Zemin, following a familiar pattern of violent political movements in the history of communist China.

Awkwardly, Falun Gong has never been explicitly banned by Chinese law, a fact that is often cited by attorneys representing practitioners in court—but typically ignored by judges due to the influence of the Communist Party’s Political and Legal Affairs Commission (PLAC) overseeing law enforcement and judicial matters.

As in previous communist political movements, officials who were more proactive in the anti-Falun Gong campaign received generous promotions and benefits.

The persecution of Falun Gong was expected to result in quick success. Instead, practitioners stood up for their faith and raised awareness about the persecution, which dragged on inconclusively and became a deepening liability for the Party authorities.

Over the years, the CCP expanded the scale and sophistication of its police state. By 2011, combined security expenditures were so high that they surpassed that of the Chinese military.

Despite the treasure and political capital spent, leaked internal 610 Office documents from 2013 described how not only was the persecution failing to achieve its goals, but that the efforts of Falun Gong adherents to speak out against the Party’s repression were on the rise.

In 2017, Freedom House estimated that there were still 7 to 10 million Falun Gong practitioners in mainland China. Minghui.org, a website founded by practitioners to document the persecution, puts that number at 20 to 40 million.

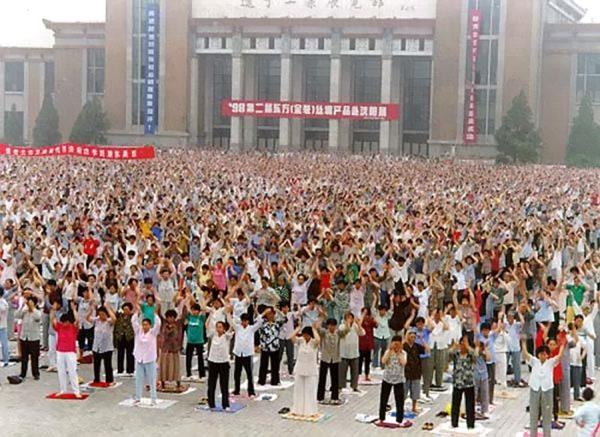

In a photo taken before July 1999, when the Chinese regime launched a nationwide persecution, Falun Gong practitioners practice the exercises in Shenyang City, Liaoning Province. Minghui.org

Practical obstacles ranging from international pressure, to the reluctance of many ordinary Chinese to turn against their law-abiding neighbors and colleagues, have been seen in the course of the repression against Falun Gong.

Minghui.org has detailed numerous accounts of Chinese police and other civil servants turning a blind eye to Falun Gong practitioners’ activities. According to a recent report by Bitter Winter, an online magazine focused on religious rights in China, public security officers in the northeastern city of Dalian pay bribes in order to be excused from the obligation of making Falun Gong arrests.

Many Chinese officials, including Jiang Zemin, have been sued in absentia for their roles in the persecution. Bo Xilai, a now-imprisoned senior Party official who is alleged to have had a close connection to the organ harvesting business, has been sued at least 10 times. This diplomatic stain contributed to Bo’s failure to be selected as Chinese vice president in the personnel reshuffling at the 2007 17th National Congress of the CCP, stunting his career path.

Factional Struggle

Since coming to power in late 2012, Xi Jinping has found himself engaged in intense regime infighting, a feud that has occasionally touched upon the anti-Falun Gong campaign. Earlier in the persecution, casting a matter of political life and death gave Jiang Zemin ideological license to promote his allies and sideline opponents. Meanwhile, he oversaw the rise of severe corruption in China and political factionalism within with the Party.Jiang stepped down from his official leadership positions between 2002 and 2004. However, the vast network of allegiances he had cultivated during his time in office gave him lasting political power.

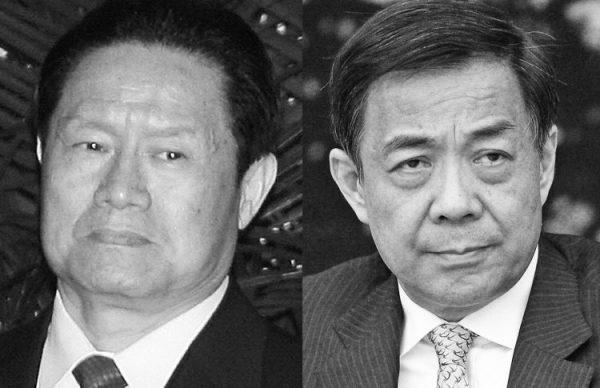

Analysts of Chinese politics have observed that Hu Jintao, leader of China from 2003 to 2012, was effectively puppeted by the Jiang faction. Prominent figures aligned with Jiang include the aforementioned politician Bo Xilai, and Zhou Yongkang, who as head of the PLAC commanded China’s vast and ever-expanding security forces. Both had built their careers persecuting Falun Gong.

Prior to Xi’s rise, Bo and Zhou had allegedly conspired to seize power, but their plans fell through due to a scandal in February 2012. Bo was arrested and sentenced the next year; meanwhile, Xi began a massive anti-corruption campaign to purge the Communist Party of other rivals. In 2013, Zhou Yongkang was investigated, then purged in June 2015. His fall came as Party authorities under Xi moved to downsize the security apparatus and strengthen central authority.

Zhou Yongkang (L), Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party's Central Political and Legislative Committee, in 2007 and Bo Xilai in March 2011. Left to Right: Teh Eng Koon/AFP/Getty Images, Feng Li/Getty Images

Internal Attrition

The moves to root out Jiang’s influence obliquely affected the persecution of Falun Gong. Many of those purged had been heavily complicit in the repression, and their political fates created an atmosphere of uncertainty among Chinese security officials, a trend noted in various reports by Minghui.The persecution itself even came under subtle criticism. In 2016, a report by the CCP’s anti-corruption agency chastised the 610 Office for failing to implement the law; earlier, the Office’s leadership post had been left empty, an ominous sign that it had fallen out of favor with the Xi authorities.

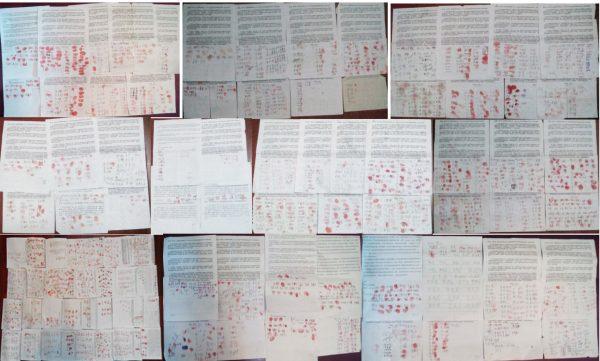

Apart from the decline of the 610 Office, developments in Chinese society pointed at a slight shift in the situation. In mid-2015, an adjustment in the judicial code made it easier for citizens to file lawsuits; this was followed by over two million formal complaints brought against Jiang Zemin for starting the persecution. The wave of lawsuits can be contrasted with an earlier such attempt in 2000, when the two plaintiffs were brutally tortured; one to death.

A small—but increasing—number of court decisions made in favor of Falun Gong practitioners has also been registered since Xi came to power, something unthinkable in the Jiang-Hu era.

In 2016, an internal PLAC report acknowledged some instances of “unfair treatment” in the course of the anti-Falun Gong campaign, and recommended that steps be taken to remedy the issue.

In 2016, 3,000 residents from Jianli County in Hubei Province signed their name and affixed their thumb prints in red ink to a joint criminal complaint against former Chinese Communist Party leader Jiang Zemin. Minghui.org

But so far, the dismantling of the 610 Office—and all other signs that the treatment of Falun Gong could change—must be qualified by the fact that the Communist Party has continued to stress its ideological and political dominance.

Minghui, which provided the document, quoted an anonymous Chinese official as saying that the persecution of Falun Gong had become difficult to handle, but that the Party “does not want to completely restore Falun Gong’s reputation, for it would be a slap in their own face.”

In nearly all respects, human rights under Xi’s leadership have been on a bleak trend, as the CCP steps up its persecution of Uyghurs, Tibetans, Chinese Christians, and other minorities. Communist ideology is also being featured more prominently in education and the media.

The 610 Office itself seems to be determined to make the best of its last days.

According to a document leaked from the group’s Liaoning provincial branch last October via Bitter Winter, the 610 Office there began a new drive to target Falun Gong practitioners and other believers in the province. The end date for the campaign is March 2019, when the 610 Office is scheduled to be closed.

The Party’s need to preserve its authoritarian rule seems to preclude meaningful improvement in Chinese human rights. But crisis lurks beyond the regime’s control, such as economic downturn, the Sino-U.S. trade war, and social unrest. As these and other challenges intensify, Xi Jinping and his colleagues may find themselves forced to make unprecedented choices if they are to keep their positions.