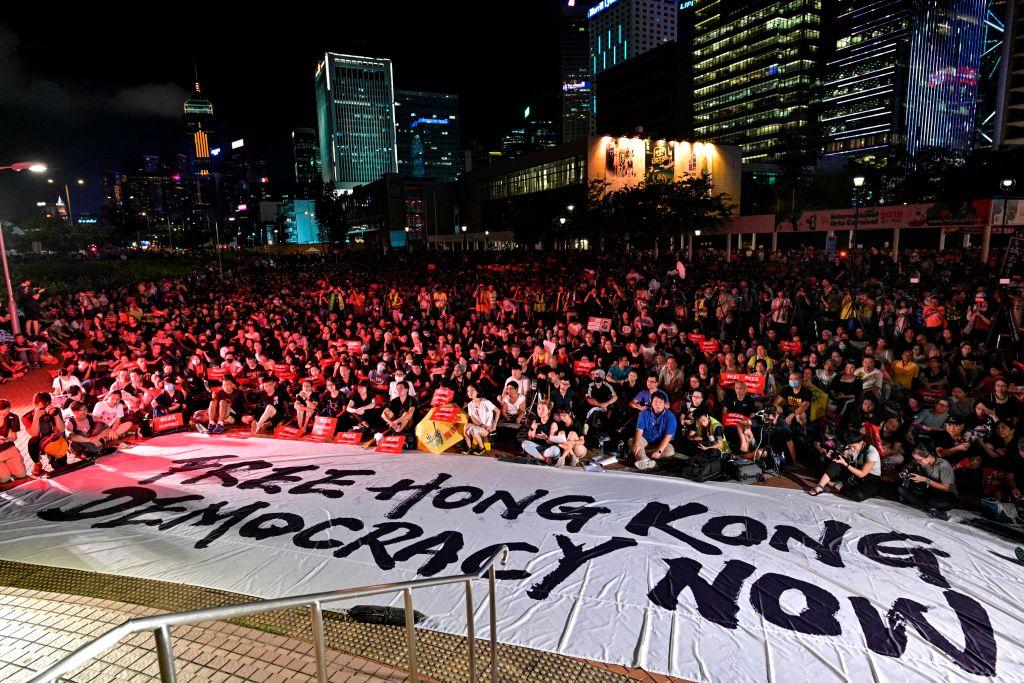

Protests against a controversial extradition bill will be the central theme of an annual July 1 march in Hong Kong opposing the Chinese regime.

Hong Kong, a former British colony, was handed back to Chinese sovereignty on July 1, 1997, with a promise from Beijing to preserve the city’s autonomy and freedoms under the “one country, two systems” model. The Chinese regime also promised universal suffrage in electing the city’s leader; today, candidates for chief executive are vetted by Beijing, and voted on by an electoral committee made up of mostly pro-Beijing elites.