The TOR330—TOR DES GÉANTS (TDG) “Journey of the Giants” is an event requiring participants to complete a circuit around the mountains of northern Italy, about 330 km (205 miles) in total, and requires going around more than 25 mountains, often at over 2,500 metres (8,200 ft) above sea level. There is one 29,608-meter (18.4 mile) uphill trek, making the race aptly named the “world’s hardest” cross-country race.

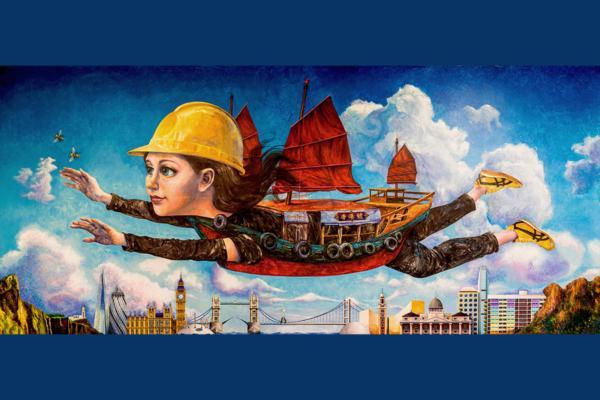

Hong Kong cross-country trekker Wong Ho Chung (also known as Sir Chung) made his debut in this year’s event, and completed the race in 77.5 hours, ranking first in Asia and eighth overall.