Commentary

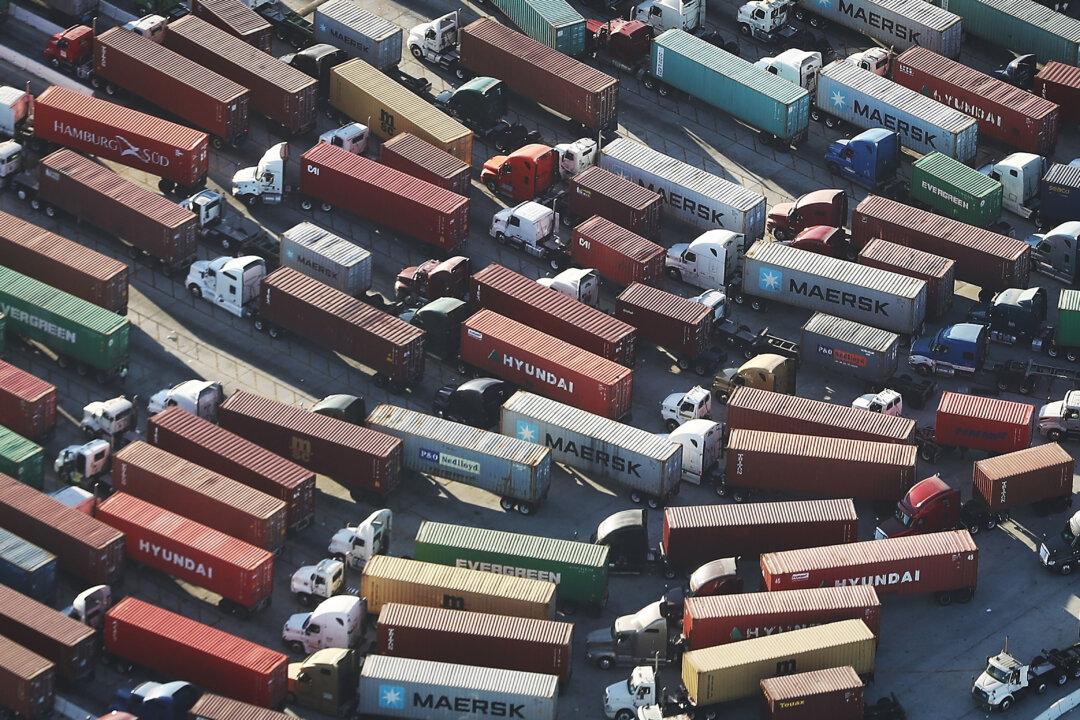

When people believed the 14-monthslong U.S.–China trade negotiations were finally drawing to a satisfactory close, Beijing made a surprising move to backtrack on all major agreements, to the great annoyance of Washington. In addition to the ensuing tariff increase, the overall U.S.–China bilateral relationship is also heading toward a danger zone.