NEW YORK—When 22-year-old Pan Jun hopped on the bus from university in Beijing on the morning of April 25, 1999, he had three requests to make to the Chinese central government: free the 45 Falun Gong practitioners who had been illegally arrested in Tianjin City; allow an environment to freely practice the popular spiritual discipline; and permit the publication of its books in China.

Pan, a Beijing native then pursuing a politics major in college, would arrive at the headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership at Zhongnanhai about two hours later, to join his parents and roughly 10,000 other Falun Gong practitioners coming from all over the country to deliver the same message.

Standing quietly along the sidewalks leading up to the compound, in a line stretching for over a mile, the petitioners made up the first large-scale demonstration since the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests that ended in bloodshed a decade earlier.

Around 9 p.m. that evening, all would be on their way home after Premier Zhu Rongji addressed their concerns and ordered the release of the arrested practitioners. The crowd dispersed in the same quiet manner in which they came, leaving no trace of litter or food scraps behind.

But the sweeping crackdown that was unleashed just three months later shattered the practitioners’ hope for a peaceful resolution.

Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, is a spiritual discipline comprising meditation exercises and a set of teachings centered on the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance. It enjoyed immense popularity in China in the early 1990s, with about 70 million to 100 million people practicing by the end of the decade, according to government estimates cited by Western media at the time.

This popularity was deemed a threat by then-CCP leader Jiang Zemin, who banned the practice in July 1999. The 610 Office—an extralegal, Gestapo-like apparatus—was established to orchestrate the persecution of Falun Gong across all levels of state.

Citizens such as Pan soon found themselves the targets of arrest, harassment, and abuse by a regime bent on eradicating the practice.

Punished for Being Good

Overnight, practitioners went from being ordinary citizens to maligned public enemies.“I was disillusioned,” Cao Suqin, originally from central China’s Henan Province and now based in New York City, said in an interview with The Epoch Times. “I had been a patriot my whole life and believed that police officers supported and protected people.”

Cao, then 33, quit her job in 1999 after local officials constantly pressured her manager to fire her. The following year, 10 days before the biggest holiday in the traditional Chinese calendar, the Lunar New Year, she was separated from her two children, aged 7 and 9, and sentenced to three years at a labor camp in Henan. In the camp, Cao was forced to make wigs and had to meet a daily quota that required her to work for up to 18 hours a day.

Cao had trouble recounting her time behind bars all those years ago. In tears, she described the torture she suffered on top of regular beatings by officers at the facility: The guards directed other inmates to inflict all kinds of torment on her, including pricking her hand repeatedly with needles until the wounds bulged, and clamping her breasts and knees with pliers.

Tian Yunhai, from northeast China’s Liaoning Province and also now in New York City, described the events following July 1999 as intensely surreal.

“From the time I was very little, I had been well-behaved and never did anything to hurt others,” he said. “So in my mind, prison and crimes were not something I had to be remotely concerned with. I never knew that for being a good person, I would spend 10-plus years behind bars.”

For refusing to give up his beliefs, Tian, now 46, has spent more than 13 years of his prime in and out of prisons and labor camps, where torture and exhausting, monotonous slave labor were the two constants.

“Once you were there, all your rights, be it personal freedom or freedom of thought, would be denied,” Tian said.

“So the only other thing they could do was apply physical torture to coerce you into mental submission.”

In the early days, hearing the crackle from the guard’s electric batons would make Tian freeze instantly, but electrocution became so commonplace that he soon adapted to it.

Tian said that one time guards handcuffed him to a heater and stripped off his outer clothing. As he was connected to the iron pipes, his body formed a huge circuit with the heater. When the guards electrocuted him, every inch of his body spasmed from the electrical current circulating through his flesh—for a full 20 minutes.

Tian recalled the guards smiling as they watched him convulse in agony. They would have continued the torture session had Tian’s family not arrived for a prison visit.

“The inner torment I was going through is impossible to put into words,” he said.

Wary of retaliation, Tian never told his family about any of this suffering during their rare moments together.

Pan recounted in an interview in New York City, where he now resides, that in the weeks following July 1999, security officers stationed themselves in front of his family’s apartment building and trailed his parents everywhere they went, from their places of work to the supermarket.

In 2002, Pan was sent to a brainwashing center, where he was held in solitary confinement in a 75-square-foot cell, which contained only a bed and a toilet. For half a year, guards allowed him only to stay in one position—seated on the edge of the bed. He was not allowed to talk, lie down, stand, or walk. Neither was he able to shower the entire time he was there.

When Pan was released, his once straight shoulders had become slumped, his legs became extremely weak from prolonged inactivity, and he suffered from temporary loss of speech.

A New Start

All three former detainees settled in the United States a few months ago. They spoke of their relief at not having to live their lives in constant fear.“It feels like coming home. No one can harass me again,” Cao said, adding that she felt relieved to find a community here.

“It feels like going back to 1999, where everyone can study, share, and practice the exercises together. Every practitioner feels like a sister or brother.”

Pan said: “America is founded on the basis of freedom and democracy. When the Puritans came here from England, they were also seeking freedom to believe in God.”

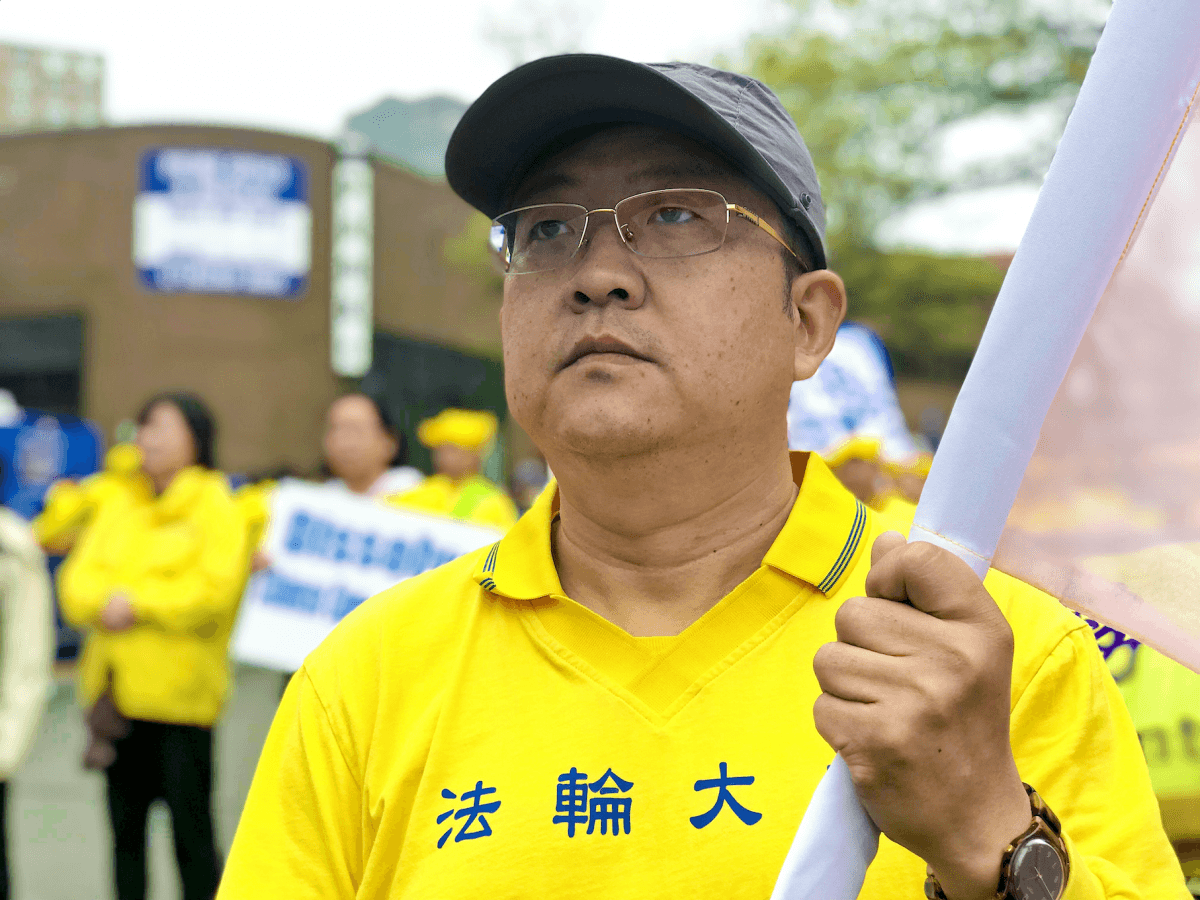

He added that being able to participate in public events, such as a candlelight vigil held outside the Chinese consulate in New York City on April 20 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Zhongnanhai demonstration, makes him appreciate his new life even more.

“I could really see how much freedom is valued here, and how close at hand it is,” Pan said.

The practitioners said their newfound freedom in the United States has empowered them to spread their stories to a wider audience.

Tian landed in New York City around the Lunar New Year. While he cherishes his adopted country, his thoughts remain with his compatriots back home.

During the new year, Tian wrote and mailed greeting cards to Falun Gong inmates at various detention facilities in China to wish them well.

“Even if cards cannot pass security inspection to reach the practitioners, it will let the guards see that the detained practitioners have not been forgotten—they still have people overseas watching over them,” Tian said.