NEW YORK—Around this time every year, what Gao Hongmei looks forward to the most is a phone call. In a conversation that would sometimes stretch for hours, she would exchange Lunar New Year greetings with her mother in China—whom she last saw face-to-face 12 years ago before she left the country—and chat about other random things in life.

But this year, distance was not the only factor keeping them apart.

Gao, originally from China’s northeastern Jilin Province, and her mother Hu Yulan practice Falun Gong, a spiritual practice brutally suppressed by the Chinese regime. Last May, Hu was arrested for distributing Falun Gong-related materials to her neighbors. The authorities formally charged Hu in July and later punished her with a five-year prison sentence. At the time, she had a three-year suspended sentence from a similar “offense” in 2018.

“They only ask for money,” Gao said in an interview from New York, where she now resides. “Everyone knows that things are expensive in prison, you know?”

Falun Gong features three core tenets of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance, along with five slow-moving exercises. After it was made public in 1992, its following in China grew to 70 - 100 million by 1999, when the regime deemed the practice’s popularity a threat and launched a nationwide campaign to eradicate it.

‘Dad Misses You’

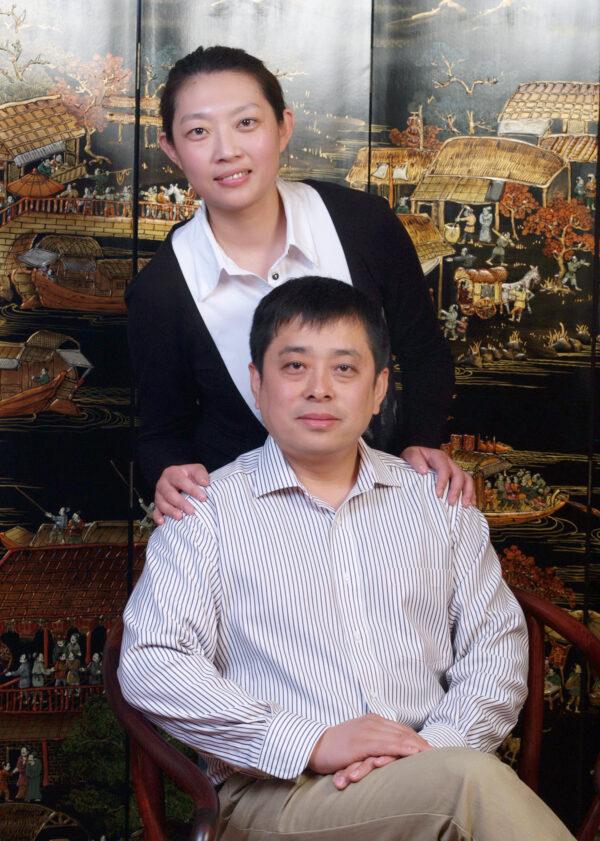

As Chinese communities worldwide usher in the Year of Ox, an untold number of survivors like Gao who escaped overseas are anxiously watching home, looking for signs that their families are safe.“Lunar New Year is a time for family reunion. But in mainland China, how many families have been torn apart?” said Wang Jing, a Falun Gong practitioner who fled to the United States from Dalian city in Liaoning Province, which borders Jilin.

Last June, police broke into Wang’s family home in Dalian without a search warrant, and arrested Wang’s husband Ren Haifei, also a practitioner. Among the valuables they confiscated were 550,000 yuan ($85,164) in cash and 200,000 yuan ($30,969) worth of memory cards and flash drives. Wang said that due to the persecution and authorities’ surveillance, her husband keeps large sums of cash at home. The tech equipment contains Falun Gong materials.

Ren went through a brutal beating by police that caused kidney and heart failure, and was sent to the hospital for emergency rescue. He was hospitalized for 19 days, before being sent to a detention center.

The 45-year-old was only able to reveal this incident in September in a phone call with his lawyer, the first of two calls the guard has granted so far.

Ren’s arrest was a huge blow to the family. Wang’s mother-in-law, who is in her 70s and lives in another province, had a stroke upon hearing the news, and is now half paralyzed.

Ren had previously spent seven and a half years in incarceration, during which the guards force-fed him through a tube to torment him. Currently held without charge, Ren has developed symptoms of diabetes, according to Wang.

“My husband is merely trying to uphold his faith, to be a better person,” Wang said. “It depresses me to think that Falun Gong practitioners are being persecuted by the communist party with impunity just for being good.”

Like Gao, Ren’s family in China were unable to see him or send clothing. When Wang called from New York to ask about Ren, the detention center refused to disclose anything, saying they couldn’t verify her identity.

They have used the virus “as an excuse to block communications with the outside … to indefinitely postpone them,” she said.

Gao’s mother spent her 75th birthday on Jan. 24 in Jilin Detention Center. Gao has called all the prison numbers she could find to reach her and sent her a hand-written letter to mark the occasion; she and friends also mailed a flurry of New Year greeting cards, not knowing whether any of these has reached Hu, or if they ever will.

A Tough New Year

Chen Fayuan, a 16-year-old studying in New York, felt something was off after three days went by without a phone call from her parents. When she checked the Minghui website, she was shocked to see her parents’ name mentioned in a police house raid from her hometown of Changsha, capital of Hunan Province in central China. The couple were among a dozen people reading Falun Gong teachings at the time.“This new year is a bit tough to get through,” Chen said.

Chen, who plays the two-stringed Chinese instrument Erhu, explained that her given name means having destiny with the “Fa,” or cosmic law, a reference to the teachings of Falun Gong.

But until she came to the United States two years ago, Chen dreaded telling people her full name because of the intense pressure. Her primary school had showcased display boards that vilified her belief, and her middle-school principal had echoed similar state propaganda in a school-wide speech, she said.

She urged people around the world not to overlook the persecution, which she said has treaded upon the basic human values.

No matter what, the teen is determined to stay hopeful. “The sky will clear up after the storm,” she said.

Wang shares the same belief. If she’s allowed to speak to her husband again, she plans on telling him, “If the hope is not lost, the dawn will not be far away.”