NEW YORK—Two decades ago, a group of ordinary citizens in China’s northeast managed to pull off a feat that no Chinese had ever done before.

For almost an hour, they took over the broadcast of Chinese state television to screen information about the spiritual group Falun Gong, which had been the target of an overwhelming official hate campaign since the Chinese Communist Party marked the practice for elimination a few years earlier.

That daring operation from the spring of 2002 is the centerpiece of “Eternal Spring,” an investigative documentary six years in the making that weaves together animation, live-action, and archival footage to tell the story of this group of Falun Gong adherents, from the genesis of the plan to its execution and its tragic aftermath. The film’s title is also the literal translation of Changchun, the name of the city where the events took place.

New York Reception

In New York City, the film has drawn two full houses since its Oct. 14 debut at Manhattan’s Film Forum. The theater was so pleased with the reception that it extended the showing for an additional week, through Oct. 27.“It really penetrated my soul,” Peter Tomczyk, the son of two Polish immigrants who witnessed the Solidarity movement that paved the way for the end of communism in Europe, told The Epoch Times after the Oct. 14 screening.

“You need to see movies like this,” he said, describing the documentary as a “beautiful illumination” of the humanity of the faith’s adherents involved in the plot.

The campaign has resulted in the detention of millions of adherents in various facilities, where they are subjected to torture, organ harvesting, and indoctrination. An untold number of practitioners have died.

The disruption of the TV broadcast shook the regime and set off mass police raids in Changchun that rounded up thousands of adherents, regardless of whether they were involved in the plot.

At least six Falun Gong practitioners connected to the effort died at the hands of police in the first 10 days following the broadcast takeover, according to Minghui.org, a U.S.-based website that serves as a clearinghouse for the persecution in China. Of the core participants, only one successfully made it out of China—after 10 grueling years in prison. Most of the others died in prison or shortly after their release. Zhou Runjun, known as Auntie Zhou among her friends, is due to be released this year after a 20-year sentence.

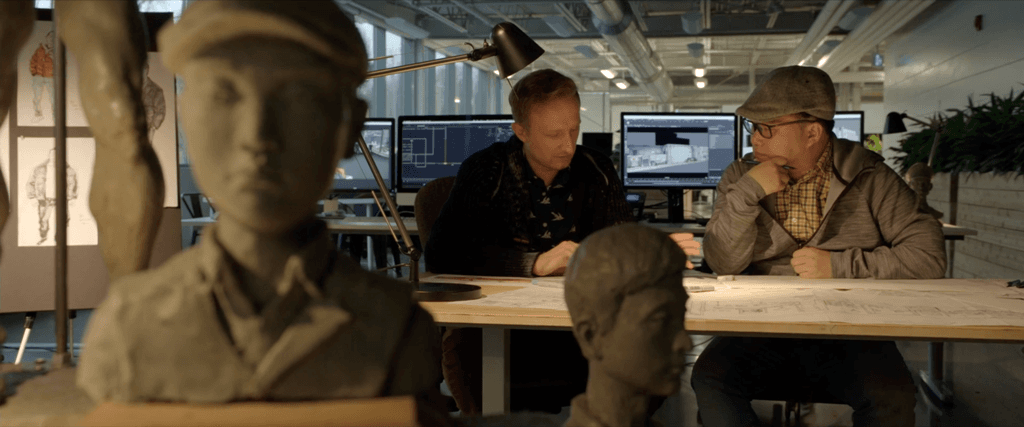

The film’s lead illustrator, Daxiong, also a Falun Gong practitioner, was himself targeted in the police raids that followed and was forced to flee his hometown of Changchun to elsewhere in China, and eventually Canada.

Daxiong, now a renowned comic book artist who has drawn for the Justice League and Star Wars graphic novels, serves as the main protagonist in the documentary. The audience follows his journey in trying to piece together the events from 20 years ago that changed both his life and those of countless Falun Gong adherents in his home city.

On top of this documentary-style storytelling, Daxiong, in his other role as the film’s lead artist, brings the bold operation to life through animation—a feature appreciated by the audience.

“Artistically, it was absolutely incredible, and the main artist ... he bound everything together,” John Robinson, a New Jersey-based neurologist and regular filmgoer, told The Epoch Times after the Oct. 14 screening.

Speaking Up for Those Who Can’t

The film’s director Jason Loftus, a Toronto native, first encountered Falun Gong in the late 1990s while he was exploring meditation, an experience that stood in stark contrast to what he had heard from Chinese state media narratives. His wife is Chinese, originally from Changchun.Hearing what Daxiong—who was arrested three times for his belief before coming to Toronto—and others had suffered shocked Loftus and his wife and prompted their desire to tell the story, the director told The Epoch Times.

The problem, the couple agreed, wasn’t just about the persecution of one’s belief. Rather, it’s that such brutality could take place in plain sight with no accountability and with few being aware of it.

“If we have a situation where people can’t speak out just because their ideas are considered wrong thoughts ... it has potentially huge consequences, not just in China,” Loftus said, using the example of Li Wenliang, the whistleblower doctor who was punished by the Chinese regime for warning his colleagues about COVID-19 during its initial spread in Wuhan. He later died of the disease.

Li “was trying to inform a few colleagues that there was a virus that was spreading; he was not trying to be a hero and sound the alarm and tell the whole world,” Loftus said.

The film was an ambitious undertaking for the small independent team, not least for its unconventional narrative choice.

“Typically, for animation, you have everything prepared, very strictly organized, before you begin. You know exactly what you’re going to produce. And in a documentary, you just keep shooting, and you’re editing and letting the story emerge,” Loftus said.

But doing both at the same time created “a big unknown”: The team never knew where different elements would end up, or whether they would make it into the film at all, he explained. Compounding the challenge was the difficulty in bringing scenes from decades ago to life while still being able to preserve a feeling of authenticity.

Externally, too, the sensitivities around the project brought another risk. In the midst of the film’s production, Chinese authorities contacted the production company’s business partner, Chinese tech and entertainment giant Tencent, over a video game their firm was releasing on the tech platform.

Tencent, which pulled the app a day after releasing it, wasn’t the only Chinese partner that cut ties with Loftus’s company—another Chinese distributor axed a mobile publishing deal. At least two Chinese cities have recently put Daxiong on a blacklist, banning his more than 100 comic books from schools.

Meanwhile, Chinese public security officers have harassed family members of Loftus’s wife in China, issuing veiled threats and saying that they know what Loftus is up to, the director said.

“They don’t tell you exactly what they know, and I think that’s an intentional thing,” Loftus said.

“What did they know? And then you can start thinking endlessly: ‘Well, did they know this? Did they know that?’ And then this way, you might censor yourself about things they don’t even know that you’re doing.”

But Loftus wasn’t going to be cowed by such intimidation efforts, not when there were survivors of repression desperate to be heard.

“We don’t face the same consequences that they do inside of China,” he said.

“If we can’t, with the freedom that we have here, help them to tell their stories, then we’re not really using the freedoms that we have, and already we’re sort of falling victim to the same type of censorship that the Communist Party enforces on the people inside China.”

Plum Blossoms Flowering

Making the tension-filled film was also a personal journey for the now-exiled Daxiong, who, over the course of the documentary, comes to a new understanding of the TV disruption, an act that he had for years disagreed with, believing that it only worsened the persecution.Even before the incident, the breathing room for adherents was already narrow.

In his early 20s, Wei Lisheng, a Falun Gong adherent, was detained at one point at the same prison with two practitioners who would later become key figures in the broadcasting plot. He recalled how, with hands trembling, he stood up alongside them to resist an “anti-Falun Gong session”—an indoctrination session where inmates are forced to watch and endorse hate propaganda against the practice. The guard kicked him with military boots that left a mark still visible on his leg today.

Despite the bleakness of the regime’s ongoing suppression, both Daxiong and Loftus wished to leave a message of hope, embodied in part in the film’s name and the plum blossoms that flower at a tense moment when the adherents, having just successfully taken over the broadcast, are trying to evade police.

Revered as a symbol of resilience in Chinese literature, plum blossoms typically bloom for one to two weeks near the end of Changchun’s harsh winters and mark the impending arrival of spring. In those flowers that thrive out of the frozen earth, the two filmmakers saw the spirit of the operation’s participants.

“It captures this feeling that yes, there are still very dark and difficult times, it’s still the winter in the sense that the persecution continues to get these people. But at the same time, people who witnessed the broadcast that they were responsible for will never be able to look at the state media propaganda the same way,” Loftus said.

“They will understand that there’s a narrative other than the Communist Party’s narrative, and that has a real impact on the future.”

For Daxiong, the story is not over yet, but rather an evolving part of history.

“It will be passed down like a torch,” he told The Epoch Times.

“Every one of us is a protagonist—not just those few cast in the movie.

“Everyone involved is contributing their part toward our future. It’s still unfolding.”

And Wei is determined to be part of that effort. He has watched the film, in which he appears as an interviewee, over 10 times and says he still tears up every time.

“I want to etch their brave deeds in my heart and tell it to the world,” he said.