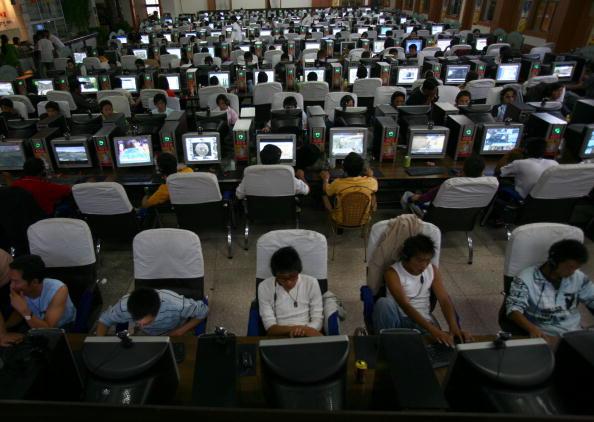

Recent events have revealed how China’s internet companies and higher education collude with censorship authorities to closely monitor citizens on social media.

On June 9, China Digital Times, a U.S.-based website that closely monitors internet censorship in China, first revealed a public bulletin announcement posted by an unnamed college in China for all its students to read. Four students, listed with their full names and class, were placed under investigation by local police for “inappropriate” online behavior.