The Chinese regime typically posts an official obituary for high-level officials no later than the date of the funeral.

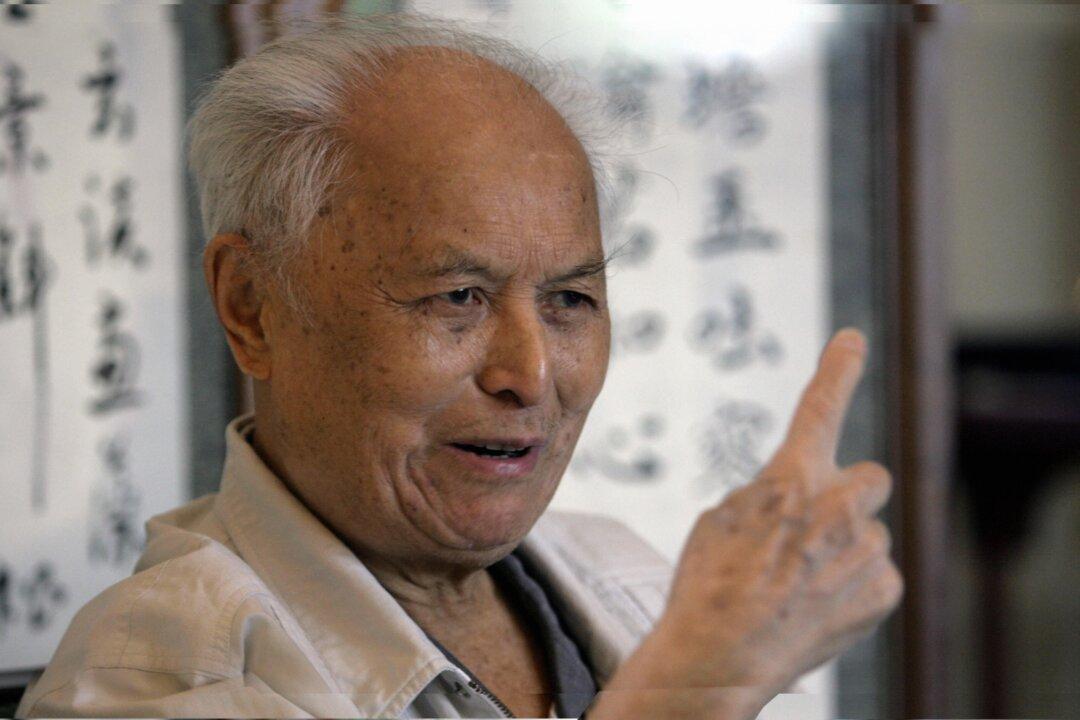

In the case of the recently deceased Li Rui, though, his obituary came eight days after his funeral—and with no mention of Li’s role as personal secretary to former regime leader Mao Zedong in 1958.

Li was arrested and detained twice because of his political opinions in 1943 and 1959. Then in 1967, he was sent to the countryside to be “reformed.”

Following Mao’s death, Li stood out as one of his biggest critics.

In 1989, Li was appointed deputy minister of the Organization Department, an agency that controls staffing positions within the Party. He asked the Party leadership not to “impose martial law or open fire on the students” who participated in democracy protests at Tiananmen Square that June.

But Li’s words angered Deng Xiaoping, then-Party leader, who wanted to crack down heavily on the students. Li was subsequently ousted.

Following his retirement in 1995, Li worked to support the democratization of China.

Notably, the obituary only included Li’s rough resume, including his birthdate and some of his positions within the CCP.

Chinese authorities organized Li’s funeral at the Babaoshan cemetery on Feb. 20, an honor reserved for high officials—though Li had refused the offer prior to his death, according to his family.

The reporter was not allowed to enter the funeral hall. When he wanted to step closer to see the couplets written on the wreaths, the security guard told him: “You are not allowed to see them. You should go look at other things [than the wreaths].”

Wang Tiancheng, president of the Princeton, New Jersey-based Institute for China’s Democratic Transition, gave his analysis on why the Party was so secretive about Li’s funeral. “We can deduce that the Party was not sure how to deal with Li’s death from the beginning,” he told the Chinese-language Epoch Times in an interview.

The Party likely had differing opinions, with some elite officials supporting not to report on Li’s death at all, while others thought the Party was obligated to post an obituary.

Li’s daughter Li Nanyang told media that her father had a habit of recording his daily life in diaries. She told the Chinese-language BBC on Feb. 19 that she would donate all of Li’s diaries from 1935 to 2018 to the Hoover Institution at Stanford University before Li’s 102nd birthday on April 13.

“His diary can reflect many things. For example, China’s so-called reform and opening [policies] did not lead to a market economy, but a state-controlled economy. Whatever the leaders say [determines the economy],” Li had said.