SINGAPORE/BEIJING—As China struggles to deal with the slowdown of the world’s second-largest economy, it has embarked on a new strategy of placing financial experts in provinces to manage risks and rebuild regional economies.

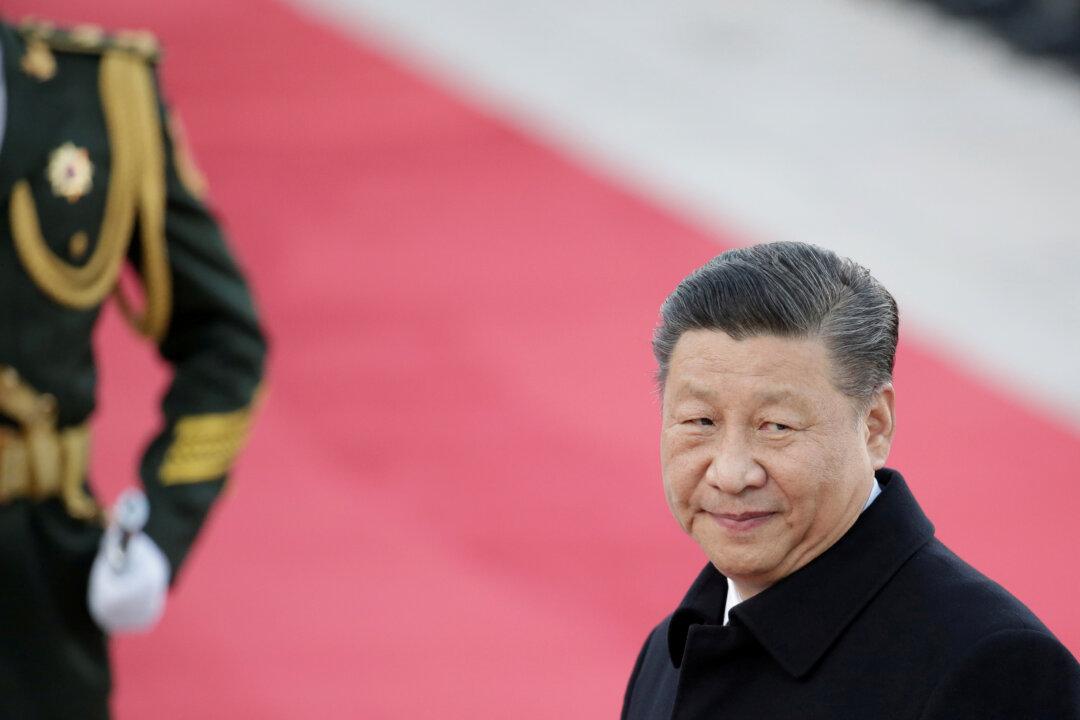

Since 2018, Chinese leader Xi Jinping has put 12 former executives at state-run financial institutions or regulators in top posts across China’s 31 provinces, regions and municipalities, including some who have grappled with banking and debt difficulties that have raised fears of financial meltdown.