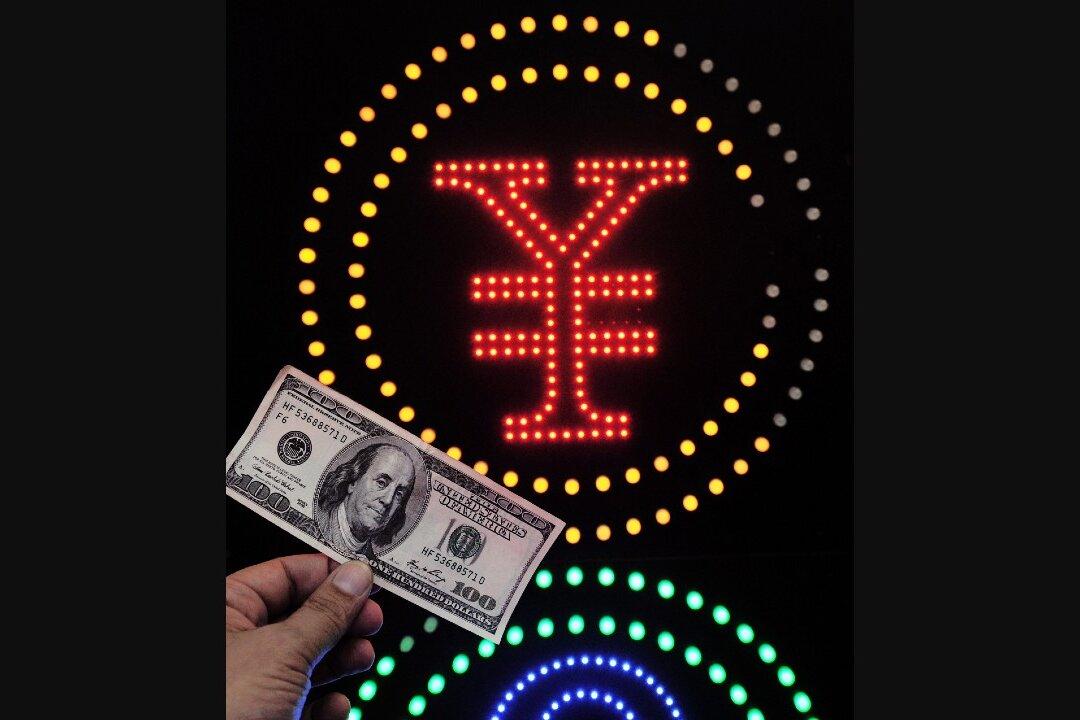

SHANGHAI/SINGAPORE—A mountain of dollars on deposit in China has grown so large that banks are struggling to loan the currency and traders say it poses a risk to official efforts to control a fast-rising yuan.

Boosted by surging export receipts and investment flows, the value of foreign cash deposits in China’s banks leapt above $1 trillion for the first time in April, official data shows.