While it’s impossible to know how many individuals were targeted by the exit ban at one time due to the lack of official data, the group found “strong evidence” showing “the CCP [Chinese Communist Party] has massively increased the number of people placed under exit bans over the past decade.”

One indicator is the surge of the phrase “exit ban” mentioned in cases on the Supreme People’s Court’s official database, which rose eightfold between 2016 to 2020.

“Counting ethnicity-based exit bans, that number is in the millions. Other kinds of exit bans likely number in the tens of thousands if not more,” Safeguard Defenders said in the report released on May 2.

“Anyone may be a target—human rights defenders, businesspeople, officials and foreigners,” reads the report titled “Trapped—China’s Expanding Use of Exit Bans.”

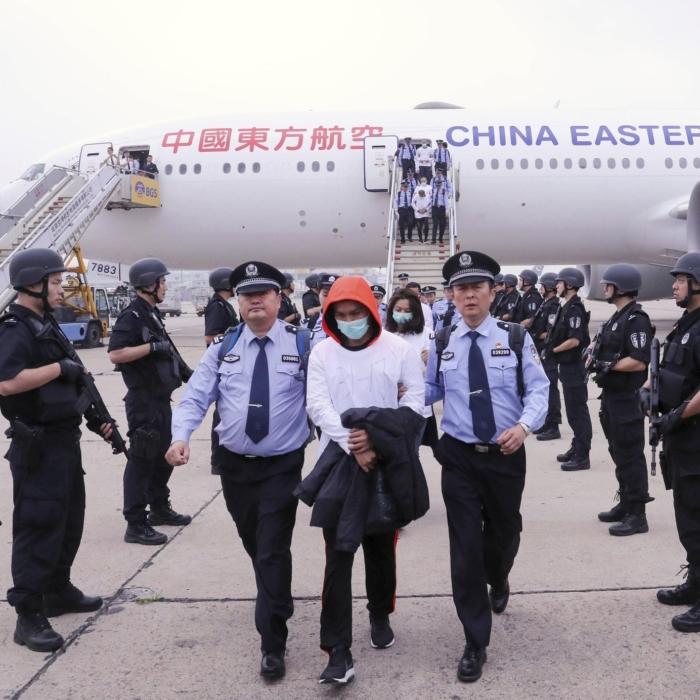

The regime uses the ban to intimidate foreign journalists, suppress rights activists, pressure their targets overseas to return to China, and control ethnic-religious groups, according to the report.

“Exit bans have become one of the many tools used by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as part of broad efforts to tighten control over all aspects of people’s lives,” it said.

The report identified at least 15 laws that allow the use of the exit ban, an increase of five since 2018. With the “complex, vague, ambiguous and expansive” local laws, any government body for any reason may issue an exit ban,” it said.

The victims are not limited to Chinese citizens. At least two dozen U.S. citizens had been barred from leaving China over a period of two years due to the exit bans, the report said, citing a 2021 estimation by John Kamm, founder and executive director of San Francisco-based Dui Hua Foundation.

A 2022 study by Chris Carr and Jack Wroldsen, professors of business law from California Polytechnic State University, found 128 cases of foreigners subjected to exit bans between 1995 and 2019; among them were 29 Americans.

The findings come amid rising concerns among foreign businesses operating in China over official scrutiny. In March, the Chinese authorities raided U.S. due diligence firm Mintz Group’s office in Beijing and detained five Chinese nationals working for the company. The Beijing office was later shut down. Beijing’s foreign ministry later said Mintz was suspected of engaging in “illegal business operations.”

Anti-Espionage Law

The increased scrutiny also came as China’s rubber-stamp legislature, the National People’s Congress, passed an amended anti-espionage law and published it on its website on April 26. The legislation, which will come into effect on July 1, allows the authorities to impose exit bans on anyone—Chinese and foreigners alike—under investigation.Chinese authorities broaden the definition of espionage to “all documents, data, materials, or items related to national security and interests.” However, it doesn’t specify what falls under national security, sparking fears of a more hostile environment for foreign businesses, researchers, and journalists in China.