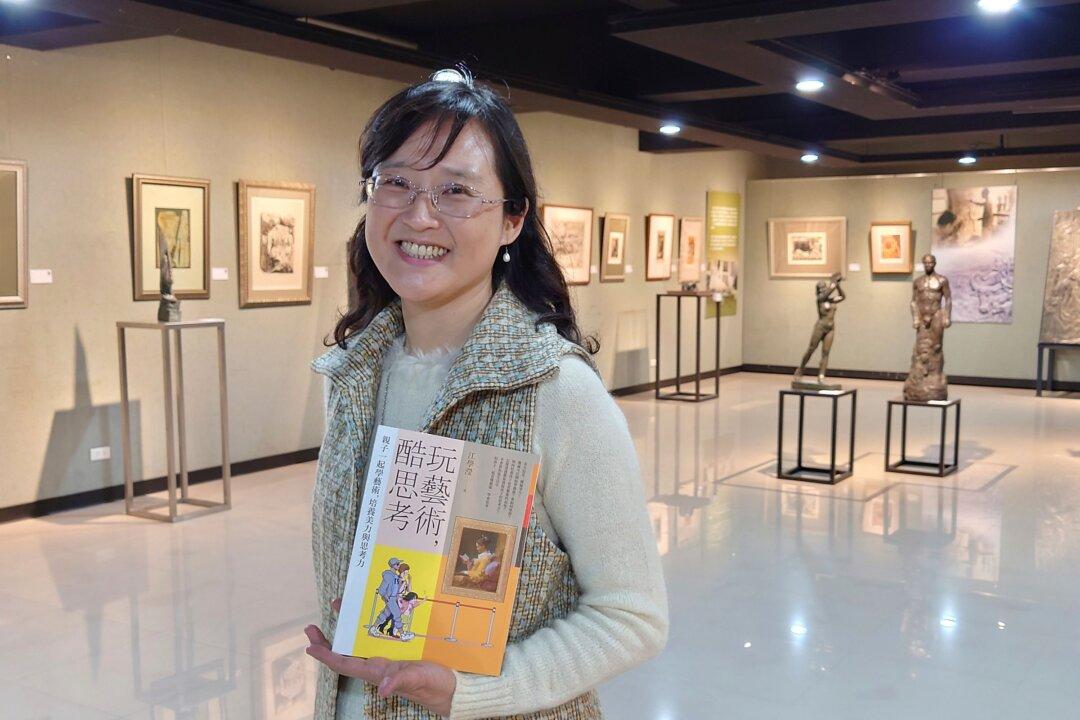

TAIPEI, Taiwan—Taiwanese author Iris Chiang hardly seems like the type whose work would be banned from publication in China. Yet four years after being sold to a Chinese publisher, her book teaching children how to appreciate art has yet to go to press, a victim of heightened tensions between China and Taiwan that are spilling over into the cultural sphere.

It’s not just about losing access to the huge Chinese market, authors and publishers say. It’s also about losing opportunities to exchange and connect, after three decades of growing contact between the two. In recent years, China has cut the flow of Chinese tourists and students to Taiwan and blocked its artists from taking part in Taiwan’s Golden Horse and Golden Melody awards, regarded as the Oscars and Grammys for Chinese-language movies and music.