BEIJING—Dissidents silenced. Security tightened. References scrubbed from the internet.

China went into customary lockdown on June 4 for the 30th anniversary of the bloody military crackdown on pro-democracy protesters, a telling reminder of the ruling Communist Party’s emphasis in the ensuing three decades since on stability above all.

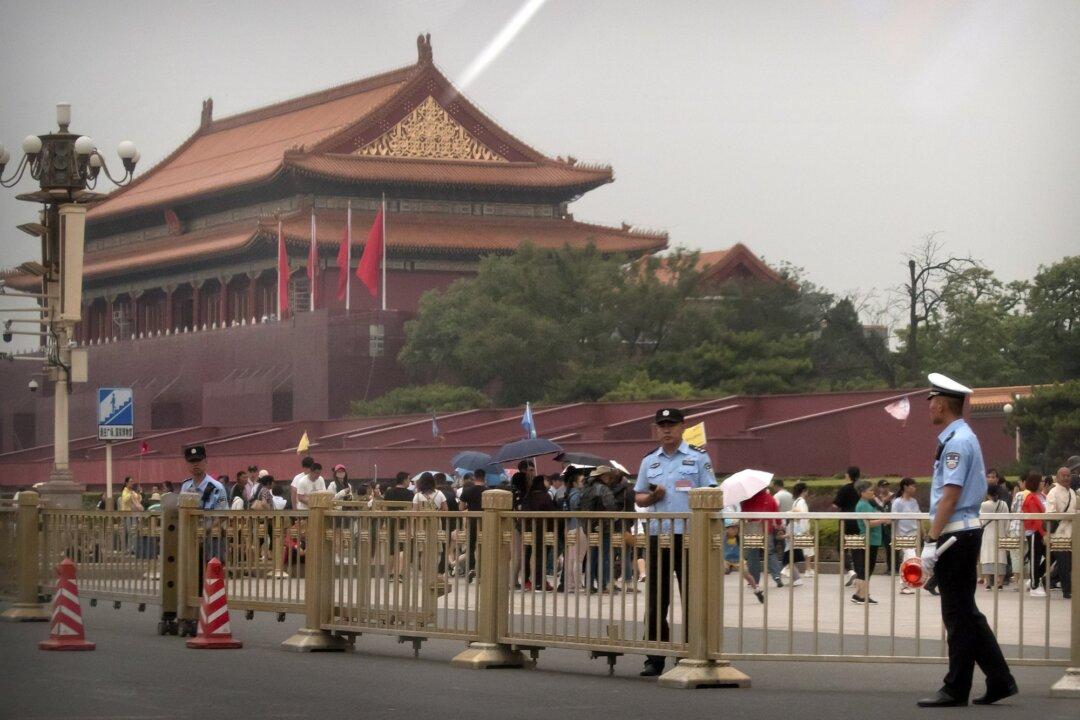

Extra checkpoints and street closures greeted tourists who showed up before 5 a.m. to watch the daily flag-raising ceremony at Tiananmen Square, the main gathering point for the 1989 protests. People overseas found themselves blocked from posting anything to a popular Chinese social media site.

The seven-week-long Tiananmen Square protests and their bloody end—hundreds if not thousands of people are believed to have died—snuffed out a tentative shift toward political liberalization. Thirty years later, social restrictions such as family size and where people can live have been loosened, but political freedom remains for the most part strictly controlled with little prospect for change.

Half a dozen activists could not be reached by phone or text on Tuesday. One who could, Beijing-based Hu Jia, said he had been taken by security agents to the northeastern coastal city of Qinghuangdao last week.

Chinese authorities routinely take dissidents away on what are euphemistically called “vacations” or otherwise silence them during sensitive political times.

“This is a reflection of their fears, their terror, not ours,” Hu said.

China has largely succeeded in wiping the bloody crackdown from the public consciousness at home, even as it rebuffs Western attempts to hold the ruling Communist Party accountable.

For many Chinese, the 30th anniversary of the crackdown passed like any other weekday. Any commemoration of the event is not allowed in mainland China, and the Chinese regime has long blocked access to information about it on the internet.

Thousands were expected to turn out for a candlelight vigil in Hong Kong, a Chinese territory that has relatively greater freedoms than the mainland, though activists are concerned about the erosion of those liberties in recent years.

Chinese overseas reported on Twitter that they were blocked from posting on Weibo, a popular social networking site. Weibo did not respond to phone and email requests for comment.

Even those who know about what happened 30 years ago are reluctant to talk about it in public. A 24-year-old designer said last week in Beijing that he thought it was quite a pity when he learned that many had died.

“But it’s really not convenient to talk about it,” he said, giving only the name he goes by in English, Tony.

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo issued a statement Monday saluting what he called the “heroes of the Chinese people who bravely stood up thirty years ago ... to demand their rights.”

He urged China to make a full, public accounting of those killed, and said that the U.S. hopes have been dashed that China would become a more open and tolerant society.

European Union foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini recalled how the European Council denounced the “brutal repression” in Beijing at a June 1989 meeting.

“Acknowledgement of these events, and of those killed, detained or missing in connection with the Tiananmen Square protests, is important for future generations and for the collective memory,” Mogherini said in a statement.

Analysts say the crackdown set the Communist Party on a path of repression and control that continues to this day.

Andrew Nathan, a Columbia University professor of Chinese politics, said China would likely be a very different place if the protests had ended peacefully through dialogue instead of force.

“They embarked on a strategy of not dialoguing with the people,” he said. “The party knows best, the party decides, and the people have no voice. So that requires more and more intense repression of all of the forces in society that want to be heard.”