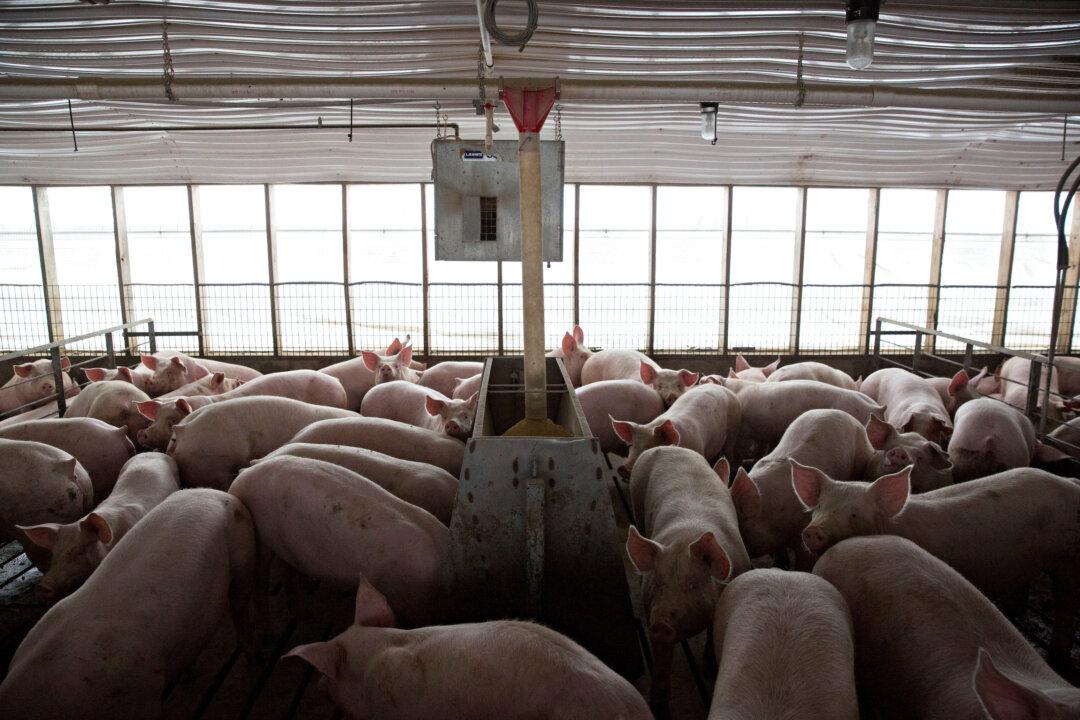

NEW YORK/CHICAGO—China would likely lift a ban on U.S. poultry as part of a trade deal and may buy more pork to meet a growing supply deficit, but it is not willing to allow a prohibited growth drug used in roughly half the U.S. hog herd, two sources with knowledge of the negotiations said.

The United States and China are trying to hammer out a deal to end a months-long trade war.