WASHINGTON—Li Hongxiang doesn’t know what normal family life looks like—he was robbed of it right after birth.

He was 36 days old when Chinese authorities threw his dad into jail. The next time they reunited, he was 10.

Upon arresting his father and grandparents, the police beat his mother, still in postpartum, demanding to know who helped put up a banner in their home city Shenyang that read “Falun Dafa Is Good.” She bundled up the baby and fled their home.

For most of those 10 years, the two bounced from place to place. After making a prison visit to his father in 2005, the police tracked his mother down and imposed on her a three year prison term. He was four.

They had committed no crime. What made them a target was their faith in Falun Gong, a meditation discipline that teaches the values of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance. Like an estimated 70 million to 100 million others in communist China, the Li family found themselves engulfed in a relentless purge campaign from the top down.

Steps away from where he stood on the edge of the meadow, rows and rows of people sat quietly, the flickering candle lights illuminating their faces and the bright yellow shirts.

The Chinese Communist Party has “no respect for people’s lives,” he told The Epoch Times.

Born a year after the persecution began, Mr. Li watched his family “completely shattered to pieces” under the regime. At age 10, his dad came out of prison a mere skeleton, with only three teeth, tuberculosis, and nearly 80 pounds lighter. He passed away a year later.

But the pain wasn’t his alone—the 23-year-old said he knows many families that have endured similar ordeals.

“I’ve experienced too much and seen too much,” he told The Epoch Times.

A Pledge Not to Forget

So much that he said he feels almost “numb” to suffering. At 6 foot 1, Mr. Li looks as if he has stored up all those dark memories inside him. His arms tensed up when he posed for a photo. He has learned to take things as they come, he said.Mr. Li didn’t get to relax during holidays in China. Those were the days police came knocking at the door pressuring them to give up their beliefs, days where he simply hoped “nothing happens today.”

Since escaping to Thailand at 13 and later settling in America, he has observed families together every day who seem happy. He might have been one of them. But how they stay so is something he now struggles to understand—he didn’t grow up in it. The regime killed it.

He has attended every one of the annual events at the National Mall.

“I constantly remind myself not to forget,” he said.

Part of it is to honor the lives lost, including his father.

‘We Don’t Deserve Such Persecution’

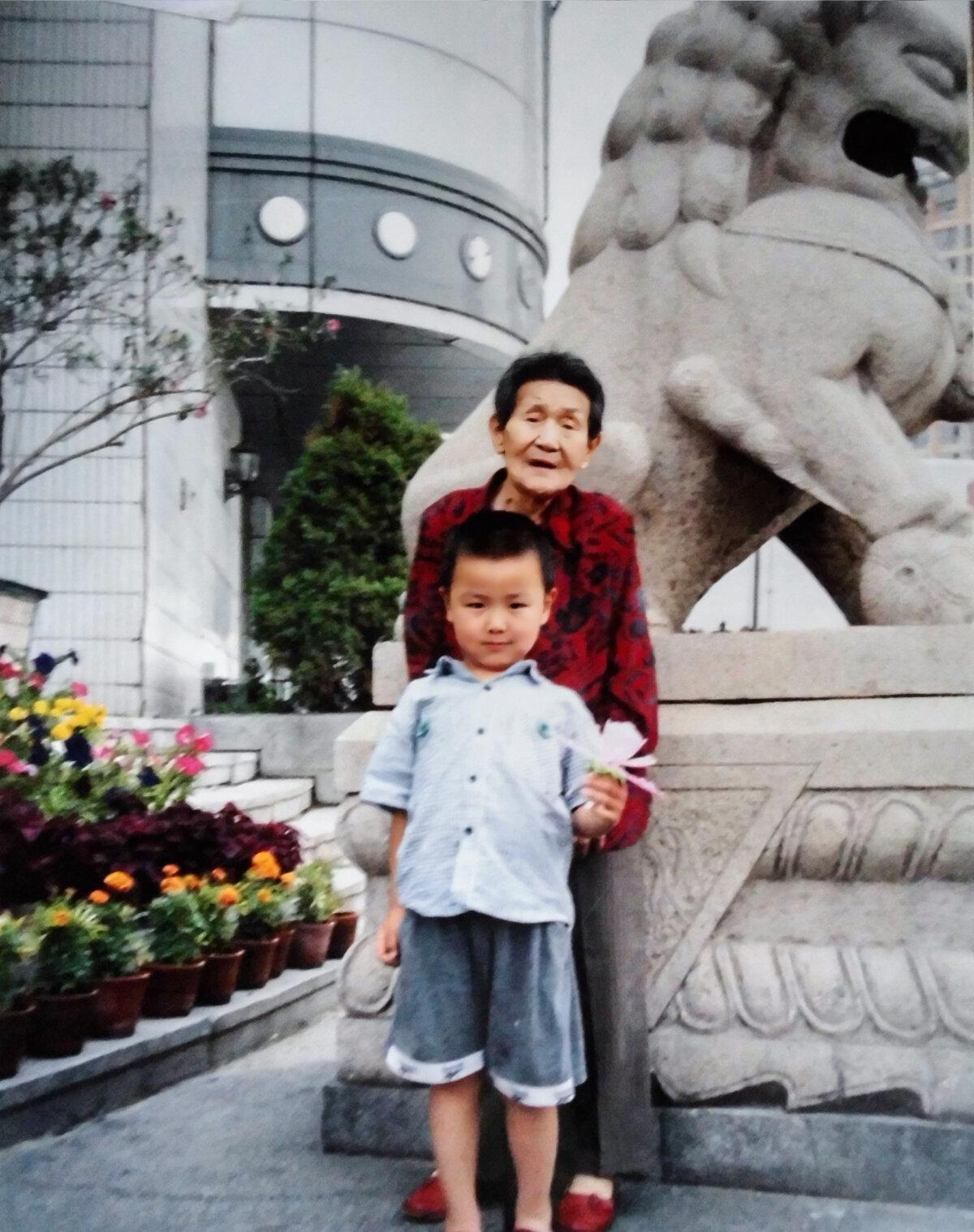

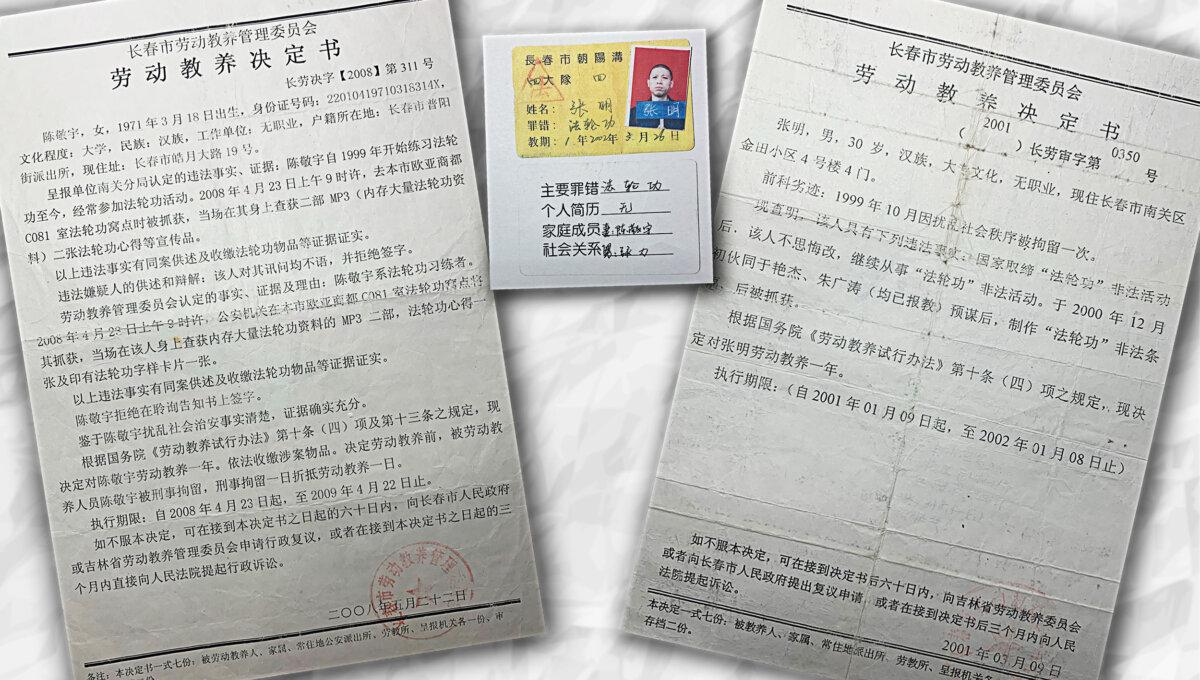

He isn’t the only one growing up in the shadow of state terror.Zhang Huaqi, who’s just months older, was similarly separated from her father in her birth year. Making Falun Gong banners was the offense stated on his 1-year sentencing document.

For the first 16 years of her life until their escape to the United States, Ms. Zhang dared not breathe a word about her faith to others. Her parents, and grandparents, faced risks of jail any time, and she feared being ostracized at school for holding a belief the regime has demonized so thoroughly.

In middle school, she remembered sitting uncomfortably in the classroom, listening to the teacher repeat hate propaganda from her textbook about a self-immolation incident—later found to be carefully staged—at Tiananmen Square.

Guilt and sadness hit her at the same time her classmates were chiming in, “buying into the lies.”

“I knew what the truth was, but I didn’t dare to stand up,” she told The Epoch Times.

During a prison visit, she saw her mother with a thinned face, her long hair chopped to the ear.

It was another eight years before Ms. Zhang learned a fuller picture about that one year jail: her mother’s nearly 10 hours of labor daily making rag dolls destined for Japan, the glue that stung her eyes, guards who yelled at slower laborers, and meal times no longer than a few minutes.

“Falun Gong practitioners are all good people,” Ms. Zhang said. “We didn’t do anything bad, and we don’t deserve such persecution.”

Speaking up now, with the freedoms they found in America, was one way they hope to make a difference for those still in China.

“I can’t change the past,” said Mr. Li. “What I can do is to help where I’m needed—to do my part.”