BEIJING—It has been three months since Chinese rock musician Li Zhi disappeared from public view.

First, an upcoming tour was canceled and his social media accounts were taken down. Then, his music was removed from all of China’s major streaming sites—as if his career had never existed at all.

Li is an outspoken artist who performs folk rock. He sang pensive ballads about social ills, and unlike most entertainers in China, dared to broach the taboo subject of the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests that ended in bloodshed on June 4, 1989.

“Now this square is my grave,” Li sang. “Everything is just a dream.”

China’s ruling Communist Party has pushed people such as Li into the shadows as it braces for the 30th anniversary of the military crackdown on June 4. Thousands are estimated to have died on the night of June 3 and in the early hours of June 4, 1989.

The Chinese regime’s effort to scrub any mention of the movement has been consistent through the decades since then, and ramps up before major anniversaries every five years. This year, the trade war with the United States has added to government skittishness about instability.

“They are certainly nervous,” said Jean-Pierre Cabestan, a political science professor at Hong Kong Baptist University. “Under Xi Jinping, no stone will be left unturned.”

Many of the actions appear aimed at eliminating any risk of individuals speaking out, however small their platforms. Bilibili, a Chinese video-streaming site, announced last week that its popular real-time comments feature will be disabled until June 6 for “system upgrades.”

Chinese Human Rights Defenders, an advocacy group, said 13 people have either been detained or taken away from their homes in connection with the anniversary. Among them are several artists who recently embarked on a “national conscience exhibit tour” and a filmmaker who was detained after tweeting images of a liquor bottle commemorating June 4.

The bottle’s label featured a play on words using “baijiu,” China’s signature grain alcohol, and the Chinese words for 89, or “bajiu.” A court convicted four people involved in designing the bottle in April.

Foreign companies aren’t immune. Apple Music has removed from its Chinese streaming service a song by Hong Kong singer Jackie Cheung that references the Tiananmen crackdown. Tat Ming Pair, a Hong Kong duo, have been deleted entirely from the app. They released a song this month called “Remembering is a Crime,” in memory of the protests.

Wikipedia also announced this month that the online encyclopedia is no longer accessible in China. While the Chinese-language version has been blocked since 2015, most other languages could previously be viewed, Wikipedia said.

The disappearance of Li, the musician, has left fans searching for answers.

On Feb. 20, the official Weibo social media account for the 40-year-old’s concert tour posted a photograph of its team in front of a truck about to embark on scheduled performances in Sichuan Province in China’s southwest.

Just two days later, however, the account posted an image of a hand wearing what appeared to be a hospital wrist band and the words: “Very sorry.” The next post, published the same day, announced without explanation that the tour was canceled and that ticket purchasers would shortly receive a refund. Fans flooded the comment section with wishes for a speedy recovery.

But the suggestion that a health issue was behind the cancellations was later thrown into doubt.

A statement published in April by Sichuan’s culture department said it had “urgently halted” concert plans for a “well-known singer with improper conduct” who was previously slated for 23 performances—the same number of concerts which Li had scheduled in the province. It said 18,000 tickets were fully refunded.

Authorities in China regularly use “improper conduct” to describe political transgressions.

Around the same time, Li’s presence on the Chinese internet was completely erased. An April 21 central government directive ordered all websites to delete any audio or video content relating to five of Li’s songs, according to China Digital Times, an organization that publishes leaked censorship instructions.

The Associated Press couldn’t independently verify the authenticity of the directive.

“There’s pretty much a consensus” among those working in the industry that Li’s disappearance from public view is due to the sensitive anniversary, said a music industry professional, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of fear of government retribution.

“He did a number of songs that were considered politically risky, making references to June 4, 1989, and so he’s been out of the picture,” the industry professional said.

The AP couldn’t confirm Li’s current whereabouts. His company and record label didn’t respond to repeated interview requests.

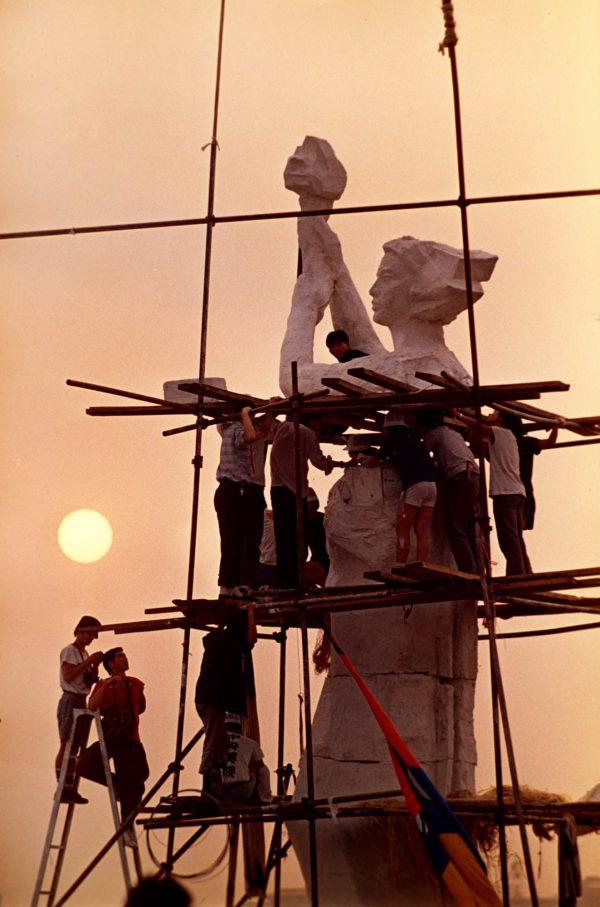

Li’s songs alluding to the Tiananmen Square protests—“The Square,” ″The Spring of 1990″ and “The Goddess,” in honor of the Goddess of Democracy that students erected—were part of his earlier works. In recent years, the bespectacled singer has avoided making public political statements, focusing more on promoting his performances.

In 2015, the state-run China Daily newspaper published a profile of Li, describing him as a performer who easily sells out concerts. After years of working as an independent artist, he signed last fall with Taihe Music Group, a major Chinese record label.

Fans who knew Li as a largely apolitical entertainer expressed bewilderment online about his disappearance. Others made veiled references to China’s internet censorship.

On Zhihu, a question-and-answer website similar to Quora, one user wrote that people posed questions every day about what might have happened to Li, but these posts always disappeared the next morning “as if nothing had happened at all.”

Another user said, “I don’t dare to say it, nor do I dare to ask.”

A fan who has been sharing Li’s music on his personal account spoke to the AP on condition of anonymity, because he feared his employers would punish him for discussing the subject.

“Everyone knows the reason for Li Zhi’s disappearance,” the fan said. “But I’m sorry, I can’t tell you, because I follow China’s laws and also hope that Li Zhi can return.”

Fans continue to circulate videos of Li’s performances online. His complete discography has been uploaded onto file-sharing websites, with back-up links in case the original ones are shuttered.