Jiang Zemin’s days are numbered. It is only a question of when, not if, the former head of the Chinese Communist Party will be arrested. Jiang officially ran the Chinese regime for more than a decade, and for another decade he was the puppet master behind the scenes who often controlled events. During those decades Jiang did incalculable damage to China. At this moment when Jiang’s era is about to end, Epoch Times here republishes in serial form “Anything for Power: The Real Story of Jiang Zemin,” first published in English in 2011. The reader can come to understand better the career of this pivotal figure in today’s China.

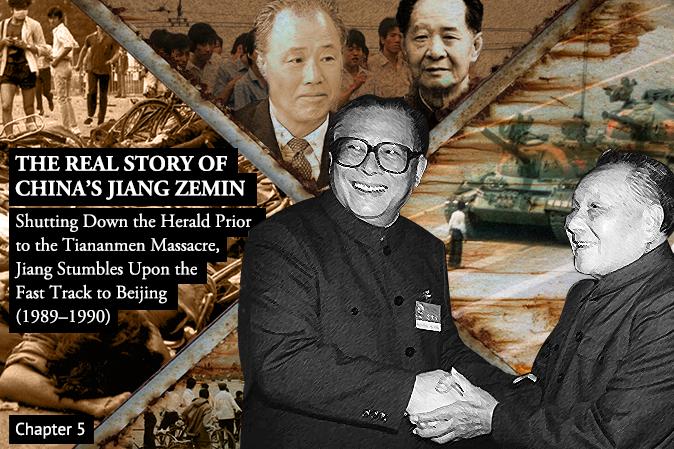

Chapter 5: Shutting Down the Herald Prior to the Tiananmen Massacre, Jiang Stumbles Upon the Fast Track to Beijing (1989–1990)

Out of everyone, Jiang Zemin was the one who benefited the most from the Tiananmen Massacre. Yet, opinions vary as to how Jiang, who was about to retire as Party Secretary of Shanghai City, became the CCP’s “core,” controlling the three powers—the Party, the government, and the army. Answers to this puzzle can be found in Robert Kuhn’s fawning biography of Jiang, The Man Who Changed China. The “biography” is, of course, more political fiction than anything, given that all of Kuhn’s interviewees were carefully selected. Fortunately, for Chinese people who have lived under tyranny for so many years, distinguishing fact from fantasy is not that hard. One could say that it is an ability born of life amidst China’s “Communist Party culture,” and thus a trait unique to that setting.1. The Fuse—Hu Yaobang’s Death