News Analysis

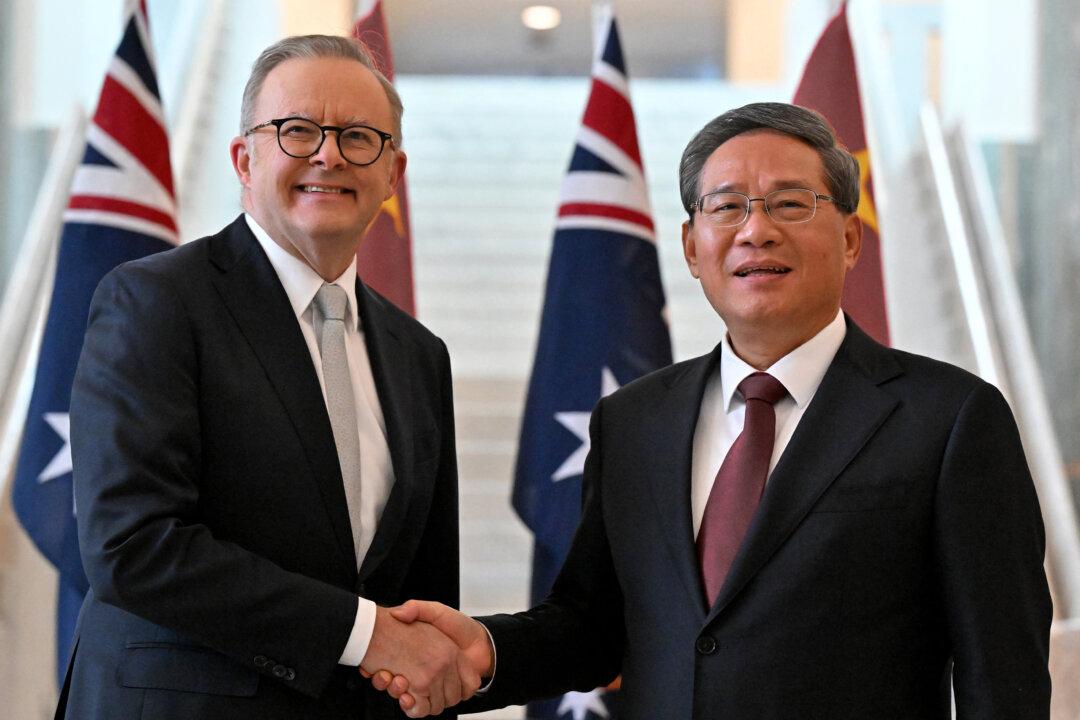

If it wasn’t for the Uyghur, Falun Gong, Tibetan, and other protesters visible at every engagement CCP Premier Li Qiang attended in Australia, it would almost appear there were no points of contention.

If it wasn’t for the Uyghur, Falun Gong, Tibetan, and other protesters visible at every engagement CCP Premier Li Qiang attended in Australia, it would almost appear there were no points of contention.