What was a conceptual cornerstone of President Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative is needed now in the United States more than ever in the face of rising threats from the Chinese Communist Party, a former Reagan administration official says.

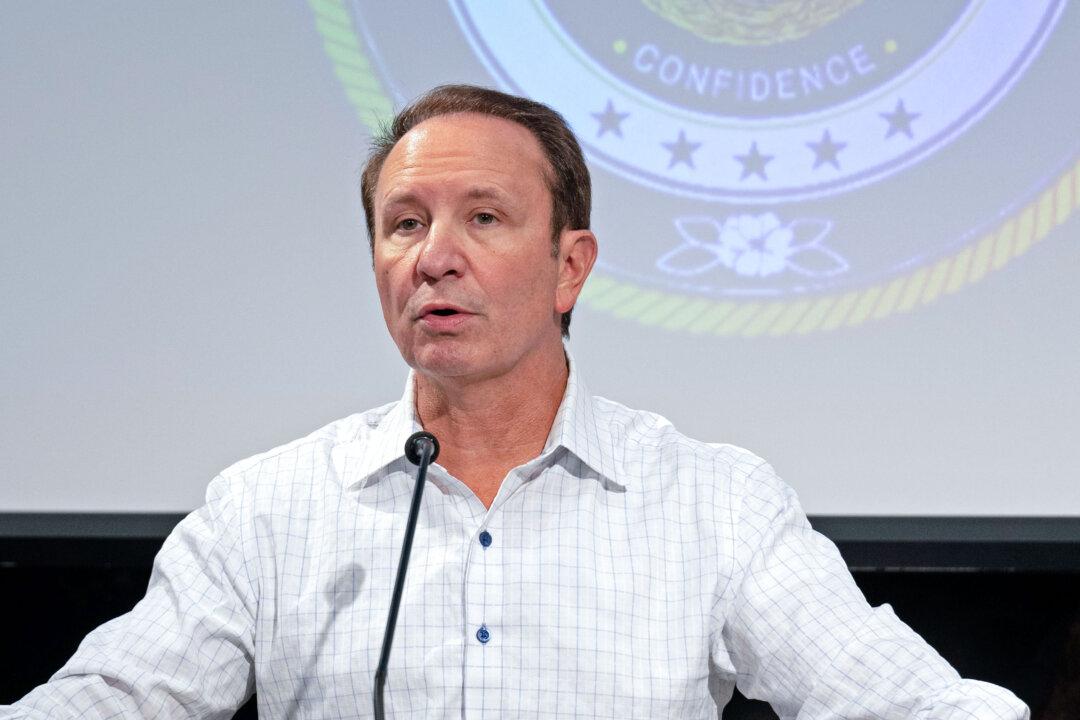

Michael Sekora, director of the once-classified Project Socrates, said the project was meant to find out what was making the United States weak—militarily and economically—and turn the tide.