Last year, just two days before the anniversary of the massacre, Hu stood outside a local government building in his hometown, the historic city of Xi’an, China. He held a placard reading “Don’t forget June 4, put an end to authoritarian rule.”

Hu’s wife was there to photograph the protest. Through a friend based outside of China, Hu then posted the image on Twitter, which is banned in China. Hu was hoping to represent pro-democracy voices from inside the country, which he found painfully lacking as a wave of events began around the world mourning the bloodshed on its anniversary.

He had no idea it would change his life forever.

Hu had been careful not to leave identifying information on the photo. He covered his face and used a photo-editing tool to remove the name of the specific district on the building plaques. Nevertheless, the Chinese police tracked him down.

A few hours after the photo was posted online, the light went off unexpectedly in Hu’s apartment. Venturing out the door to check on the issue, Hu was stunned to see more than a dozen people waiting outside. One man pinned Hu down while pressing a gun to his waist. The others rushed into the apartment.

“That man in the photo—is that you?” another man asked Hu, holding a copy of the photo Hu had posted to Twitter.

A “yes” from Hu was all that was needed for those men to begin ransacking his apartment. Hu’s 7-year-old son, unsure of what was going on, started to cry.

The men, who never identified themselves, handcuffed and interrogated Hu overnight before detaining him in a detention facility that had been converted from a hotel. There, he received constant threats and was forced to sign two documents acknowledging guilt for “disrupting social order” and “picking quarrels and provoking trouble”—both of these vague charges are commonly used by Beijing to silence dissent.

Even after being freed on bail, Hu had to report his activities to the local police. Another incident like this could get him charged with the more serious offense of “subversion of state power,” which has a maximum penalty of life in prison, the police warned.

Forbidden Memories

Exactly one year after that police raid, on the eve of another June 4 anniversary, Hu is in California to tell his story, now in exile from the communist-ruled country he has lost faith in.He spoke of the many sleepless nights, haunted by nightmares in which police would hood and take him away in front of his crying children. He has taken to using sleeping pills to get through the night.

Disillusioned with the regime and seeing no future for him in China, Hu, along with his wife and two children, embarked on a harrowing 50-day journey to escape to the United States via Latin America. His escape from China wasn’t unlike what many Tiananmen protesters had to go through more than 30 years ago when the regime started hunting down those involved in the movement.

On the road, the Hu family had sat through stormy waves on a speedboat that lacked basic protective devices and briefly lost track of their son while trekking through thick rainforests.

He feels lucky to have made it out despite the many perils he suffered, noting that as the anniversary approached, Chinese authorities have harassed, threatened, or detained a number of prominent dissidents inside the country to ensure that nothing would happen to mark the occasion.

“The Communist Party has always wanted to erase this part of history so that it can go on to deceive people. That’s why it’s all the more important to remember,” Hu told The Epoch Times.

“You can see nothing in mainland China, not a word about the incident at all,” Hu said.

A Defiant Spirit Lives On

But if the regime aims to have people forget, there are communities out there determined to make sure that it won’t get its way.On June 2, the June Fourth Memorial Exhibit opened in New York.

Situated in a cramped office space on Sixth Avenue in Manhattan, it marks the world’s only permanent exhibition dedicated to the Tiananmen demonstrations after a similar museum in Hong Kong was shuttered under pressure from authorities. The address of the venue, 894 Sixth Avenue, happens to match the date of the incident.

“It’s a symbol of defiance,” said the exhibit’s executive director, David Yu, noting that he hopes that the venue can help people in the country distinguish China from the ruling communist regime.

“Many Americans would immediately associate Chinese people with the Communist Party,” he told The Epoch Times. “But by having this June Fourth Memorial Exhibit here, they may ask about it and realize that’s not true. These are Chinese people, but they oppose the communist totalitarianism. They are the freedom fighters.”

The exhibit features many items preserved from those times, including photos, a bloodstained shirt from a Chinese reporter who was beaten by armed police while trying to cover the suppression, and a tent donated from Hong Kong that housed the pro-democracy students during their last few days on Tiananmen Square.

Black banners with slogans popular during the 2019 Hong Kong mass protests against Beijing’s encroachment, along with videos and posters from the movement, are on display in a dedicated room to showcase the “shared ideals” of people from the mainland and Hong Kong, according to Yu.

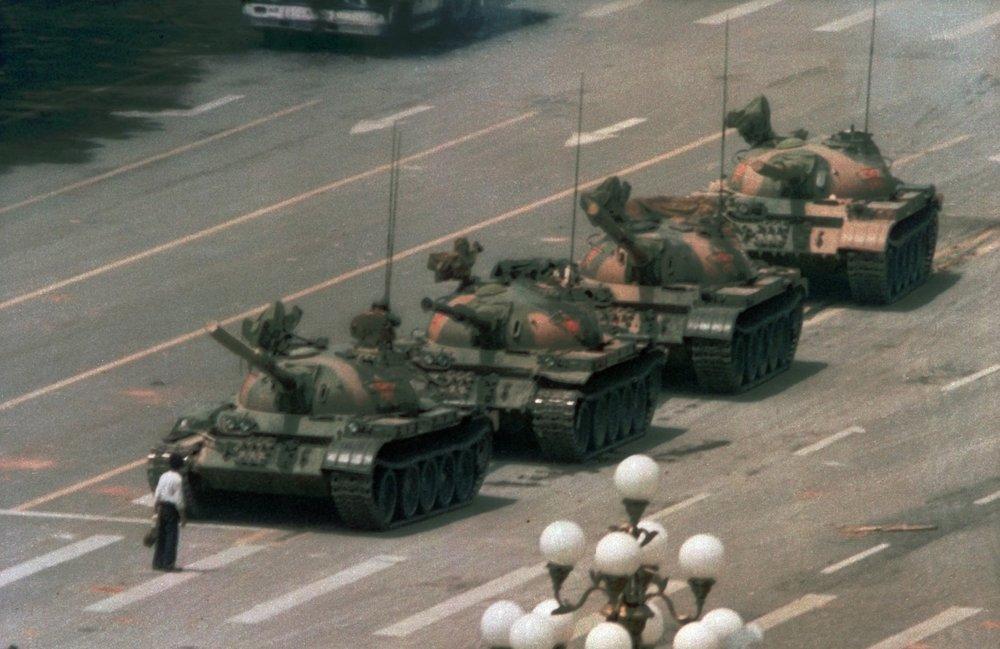

Yu was teaching at Dartmouth College while working on a doctorate in economics at Princeton University when tanks rolled down on Tiananmen Square in 1989. For years afterward, he threw himself into pro-democracy work, even delaying finishing his doctorate paper for more than a decade.

“I think I’m a rather stubborn person,” he said, reflecting on his advocacy work over the past three decades. “Once I decide something should be done, I will keep going at it without much change.”

Hu, while unable to be there for the exhibit’s opening ceremony, said he'll definitely visit when he gets the chance.

“These are irrefutable evidence of how cruelly the communist party treated the students and citizens,” he said. “The revelation of the true face of the Communist Party.”