At Taiwan’s Taoyuan International Airport, the air was tense as a Chinese author, her husband, and their 5-year-old son huddled together, clutching each other as if the world could crumble around them at any moment. Their eyes, hollow from exhaustion, darted anxiously across the crowded terminal, scanning for any sign of danger.

This wasn’t just a tourist visit; it was a desperate flight from a nightmare that had haunted them since they left China on July 22. Taiwan was their third attempt after failing to obtain protection in Thailand and Singapore.

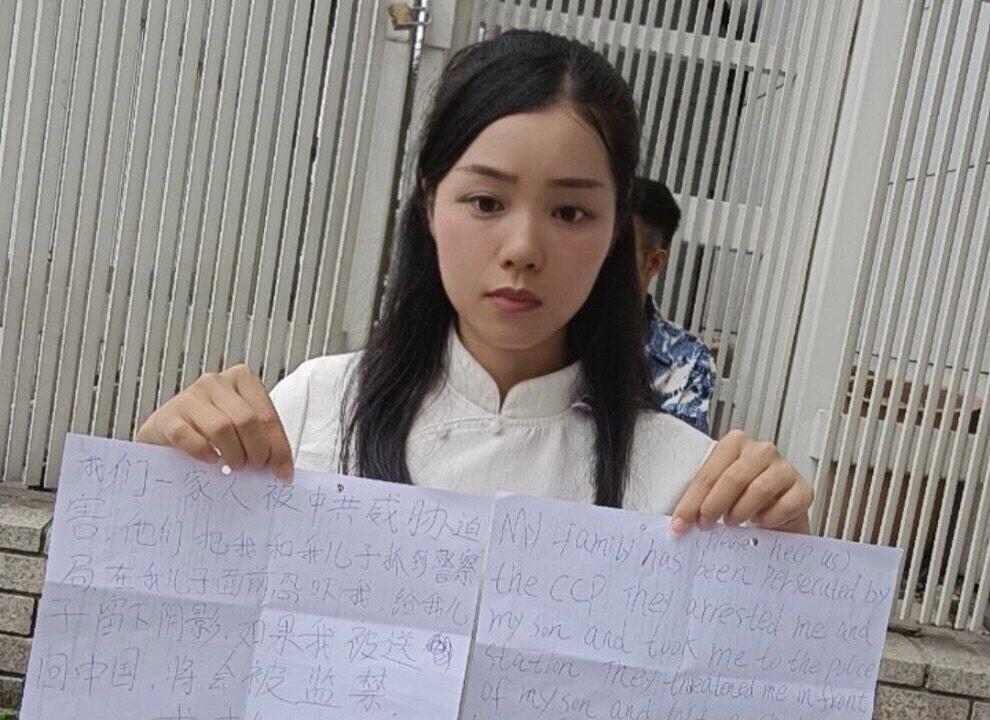

“All we want is a normal life—free from fear and where human rights are respected,” Deng Liting confided, her voice barely above a whisper, to The Epoch Times from an undisclosed location in Southeast Asia on Aug. 22.

For Deng Liting, known by her pen name Mo Lu, this fight for freedom is a battle for her physical safety and for preserving her creative freedom. As a Chinese author who dared to speak out against the atrocities committed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), her very existence had become a target.

Now, she has found herself fighting to keep her family safe, and faces the challenge of staying who she is—with the spark of creativity and truth that had defined her life.

Her nightmare began with a seemingly simple act: posting an online message about “presenting a bouquet of white flowers to the square” a day before the 35th anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, a violent government clampdown on pro-democracy students on June 4, resulting in thousands, if not tens of thousands, of deaths.

The subtle hint of a memorial drew the full wrath of the Chinese authorities. On June 4, just days after taking her son to travel for the Children’s Day holiday, Deng’s life was upended when police tracked her down to a hotel in Chongqing, a Southwestern city directly governed by the central CCP regime.

“Did you think we wouldn’t be able to find you? As soon as you checked into this hotel, your identity information was uploaded,” the officers said as they dragged her into a nearby police station, her terrified son clutching her hand, she recalls.

The interrogation was brutal, a calculated attempt to break her spirit, she said. “They threatened me, pushed and pulled at my clothes, all the while my son was watching,” Deng recalled, her voice shaking as she relived the trauma.

“Whenever I didn’t tell them the answers they wanted to hear, they would slam the table in anger. My son was terrified by the situation. It was as if my son was their hostage. They kept threatening that something bad would happen if I didn’t cooperate.”

During the grueling interrogation, despite their relentless threats and demands, Deng stood firm. She didn’t admit guilt. She and her son were eventually taken back to the hotel after the three-hour ordeal.

“My son was so scared; I told him to close his eyes and think about something else, but he was still afraid even with his eyes closed—he’s just a child, after all,” Deng added.

Her greatest fear—that this experience would leave a permanent scar on her 5-year-old child—quickly became a reality. “He developed a severe fear of police cars. Whenever he hears a police car, he shrinks back in fear, his neck tensing up,” she said.

Realizing that staying in China was no longer an option, Deng and her family fled the country on July 22, embarking on a perilous journey through Thailand and Singapore before finally arriving in Taiwan. Yet the shadow of the CCP’s long arm followed.

Due to Taiwan’s lack of formal refugee laws, Deng and her family had to go on the run again, this time to an undisclosed location in Southeast Asia.

“Since coming here from Taiwan, my biggest concern has been the possibility of being deported because this is Southeast Asia,” Deng said, adding that she doesn’t feel safe in Southeast Asia because of the CCP’s influence in the region. She said she remained grateful to Taiwan for not sending them back to China, acknowledging the self-governed island’s difficult position.

“But now, we needed to find somewhere safe and within a price range we could accept,” she added.

“The person I feel the most sorry for is my child. I’ve dragged him around, constantly on the move, and he knows we’re being pursued,” Deng said, her voice breaking with emotion.

“My husband has also endured a lot of hardship with me. This is what pains me the most and what makes me feel the worst when I think about it, and I still feel deeply distressed about it now.”

However, the stories she has yet to tell, the truths she has yet to uncover—they are what keep her going, even as the world around her grows darker.

Personal Awakening and the Weight of Truth

As Deng’s journey through exile continues, the truths she uncovered in China weigh heavily on her. Her love of reading and writing first opened her eyes to the harsh realities of life under the CCP. Now, those same truths drive her forward, even as the dangers mount.For her, books were more than just a source of knowledge; they were a gateway to understanding the world beyond the tightly controlled narratives pushed by the CCP. Bypassing the CCP’s internet firewall and reading banned books led her to a deeper awareness of the atrocities committed by the Chinese regime, from the Cultural Revolution to the more recent persecution of dissidents and religious groups.

The Fight for Freedom

In 2021, Deng published a novel entitled “A World Without Souls.”The novel follows a young girl in a dystopian world stripped of freedom and spirit. Amid personal tragedies, she embarks on a mystical adventure with her childhood friend. Their struggles for survival and search for redemption mirror the harsh realities of contemporary Chinese society under the CCP, offering a profound reflection on a world in turmoil.

Despite the dangers, Deng never lost sight of her goal: to become a voice transcending her time and write novels that capture her unique perspective.

“Now, I plan to continue thinking about how to get to a safer place,” Deng said, her determination unwavering despite the odds. “Without our lives, how can we pursue freedom?”

Holding on to Faith

In her darkest moments, Deng draws strength from her Christian faith—a faith that has guided her through the most challenging times and given her the courage to keep going. Her journey to Christianity was gradual, shaped by years of searching for spiritual guidance. But in China, openly practicing Christianity comes with grave risks.Deng was raised with Buddhist teachings. The traditional Chinese beliefs shaped her worldview until 2020. Her earlier works often reflected this deep-rooted faith in Buddhism.

As she continued writing and exploring different ideas, her perspective changed. And by 2021, she had become a Christian. After that, Deng said she “didn’t dare to tell others” out of fear of being seen praying. In her hometown, Lingshan County in Guangxi Province in Southern China, a Christian church had been demolished, likely due to persecution. “When I tried to find it, it was gone,” she recalled. Though there were rumors of underground churches, she said she couldn’t connect with them.

In China, the Christian faith is also under the CCP’s control. She said her online posts embedded with her Christian faith were blocked. She said she even received a message from online police asking if she had credentials from a Christian church.

“They were essentially saying that I needed to become part of the state-controlled church and get a license, or they wouldn’t let me post,” she added.

Despite the challenges, Deng’s faith remains her anchor. “Everything I do is guided by God, like my escape from the CCP,” she said. “Despite being turned away from Taiwan and facing many hardships, we still see God’s hand in our lives. This has brought us some peace of mind.”

“We thought we might spend our whole lives trapped there. But after praying, God revealed to me that I should leave China for my child’s sake,” she added.

This sense of purpose keeps Deng focused on the future, even as she navigates life in exile. She is determined to continue fighting for a better life for her family. She hopes to find a safe haven in a Western democracy where they can stop running.

She knows that her ability to write and think freely will be severely constrained as long as they are on the run, but giving up is not an option.

“I don’t like following trends or writing things that are the same as others. I want to express my individuality through my novels, to write something truly one-of-a-kind,” she said.