The Chinese regime is reportedly planning to scrap an industrial policy criticized by the Trump administration as protectionist, in favor of a program more hospitable to foreign companies.

The new policy is set to be introduced early next year, according to the Journal.

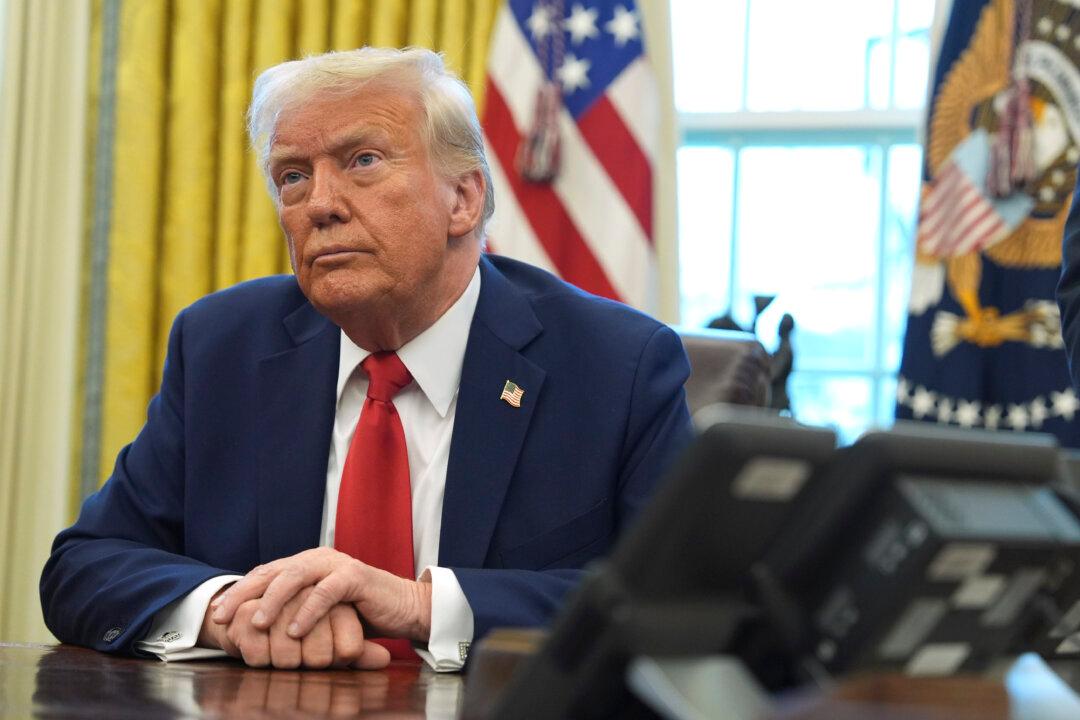

The move comes as the President Donald Trump and Chinese leader Xi Jinping agreed to a temporary trade truce in Argentina on Dec. 1. The two sides are expected to negotiate over U.S. demands for stronger Chinese protections for U.S. intellectual property, an end to forced technology transfers and greater market access to China for U.S. companies.

Meanwhile, references to Made in China 2025 have been dropped in a new guidance to local governments in China.

In its 2016 guidance to local governments, the State Council, or cabinet, said local governments that promoted the implementation of “Made in China 2025” while encouraging industrial growth and manufacturing upgrading would be given priority support.

Made in China 2025

The Made in China 2015 strategy is core to China’s aim to transform itself into a global superpower by 2050, and be more competitive in sectors such as robotics, aerospace and clean-energy cars.The Trump administration has repeatedly slammed the policy for undermining fair competition, by sanctioning state subsidies of domestic industries and forcing the transfer of technology from foreign companies.

The plan has been also criticized for being reliant on the theft of technology and trade secrets, primarily targeting the United States and Europe.

In recent, Chinese companies have been active in acquiring and investing in foreign firms in order to obtain their technological innovations. According to the Taiwan-based Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research, in 2016, the top two industries where Chinese firms have engaged in foreign acquisition deals are manufacturing, about $30 billion worth, and information technology and software, about $26.4 billion worth.

In addition, the Chinese regime forces American and other Western firms operating in China to transfer their tech knowledge to their Chinese joint-ventures, in exchange for market access.

In late June, the regime decided to tone down its nationalistic tech ambitions as President Donald Trump’s punitive tariffs on Chinese goods loomed closer.

China Standards 2035, announced in January, seeks to accelerate the development of technical standards in key technology sectors, with the aim of eventually exporting them to the international market. In this way, China would no longer need to rely on foreign technology, as domestic companies strive to become market leaders through the control of standards-reliant patents and technologies.