WASHINGTON—As the night fell on July 20, over 1,500 Falun Gong adherents sat on the National Mall, carrying candles to commemorate those who have died as a result of the Chinese regime’s repression.

Liang Guiyu, 53, a resident of New York’s Flushing, originally from northeast China’s Shandong Province, was one of them.

“July 20 is a nightmare to me. Whenever I recall July 20, I’m in pain, and my heart is trembling,” Mr. Liang said.

Falun Gong, also called Falun Dafa, is rooted in Chinese traditional culture and centers around the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance. Before the persecution began in 1999, the spiritual belief had an estimated 70 to 100 million adherents in China.

Since 1999, tens of millions of adherents have been targets of a brutal suppression effort designed to break them physically, financially, and socially. This includes forced firings, family separation, detention, harassment, surveillance, forced labor, torture, and forced organ harvesting.

An untold number of practitioners have perished.

A 300-Mile Walk

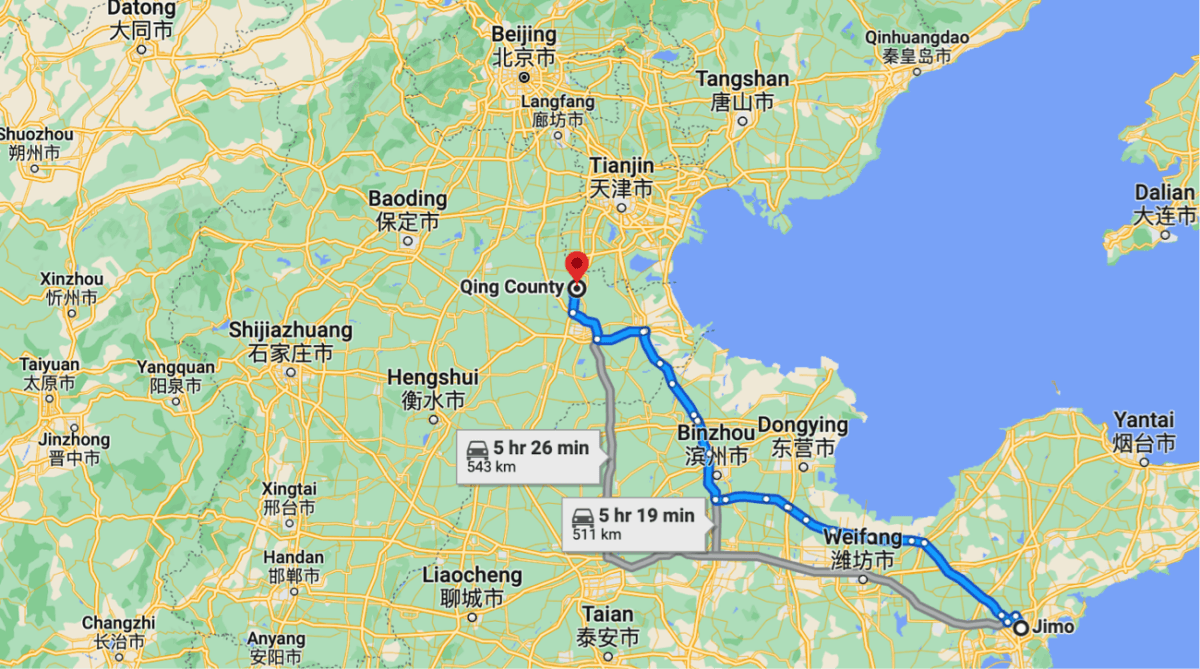

One year into the persecution campaign, Mr. Liang decided to embark on a 400-mile journey by foot from Shandong to Beijing.He, like many other adherents at the time, wanted to tell the CCP central authorities in the nation’s capital that Falun Gong was good and that the persecution was a bad decision. He couldn’t take public transportation because police officers were stationed at train and bus stations to round up Falun Gong adherents planning on making that journey.

The then-30-year-old farmer left home on July 10, 2000. He walked every day from 3:30 a.m. to 9:30 p.m.

Mr. Liang had no money on him because his family had taken it away and watched him day and night after he went to Beijing’s Tiananmen Square the previous year to peacefully protest the persecution. All he had with him was a spare pair of shoes.

He slept by the roadside at night and ate leftover food given by donations or restaurants. He walked through forests, cemeteries, and crossed streams to dodge local police officers who came after him.

July in China was very hot that year with temperatures often over 100 degrees (40 Celsius). He often poured water over his head at gas stations or soaked his clothes in stream water to cool down his body. After seven days, he discarded his first pair of shoes and developed blisters soaked in blood.

After 10 days of walking, he arrived at Qing County in Hebei Province, about 100 miles south of Beijing and about 300 miles away from home. He got a bit lost, so he asked a taxi driver for directions to Beijing. Within minutes, the taxi driver reported him, and he was captured by the police and taken back to his hometown, a rural village in Qingdao, a port city in Shandong Province.

For 15 days, he was detained by local village authorities. The village had some one-story single-room houses near its government building and used these empty buildings as a black jail.

For half a month from late July, Mr. Liang was handcuffed to an 8-inch wide, 10-foot tall iron pole that stood in the courtyard in front of the house. He was handcuffed most of the time, except for when he was taken elsewhere to suffer. Because it was very hot, he had to stand and make sure his arms didn’t touch the pole so they wouldn’t get burnt.

His breaks from being handcuffed to the pole usually came during mealtimes. But once, police officers threw him into the restroom while handcuffed and urinated on him to humiliate him.

But the worst humiliation he suffered was when local CCP officials handcuffed him to an idling motorcycle on the roadside. He was forced to sit on the street for about two hours enduring a session of public humiliation. In that small village where Mr. Liang grew up and went to school, everyone knew each other.

“They humiliated me to break my will, but I didn’t feel ashamed because I did the right thing to safeguard Falun Gong’s reputation, and I didn’t violate the law,” he said. “They realized that it was no use on me and stopped humiliating me in public.”

Officials didn’t stop their campaign of torment until Mr. Liang, in a desperate attempt to end his suffering, dashed to the iron pole after a restroom trip one day in August. “I was going to use my life to resist the violence,” he told The Epoch Times.

Fortunately, he tripped before hitting the pipe, so he didn’t die from it. Still, he heard a loud clanging sound and fell down. During his fall, he saw the village officials in the administrative building next to the detention site staring at him through the windows.

After that, he was detained for 35 more days but spared from being handcuffed to the pole. His family had to pay 3,000 yuan, or about $400, to secure his release in September 2000.

Eventually, the family borrowed the money for Mr. Liang’s wife, also a Falun Gong adherent, to escape to the United States in 2012. In November 2017, Mr. Liang came over to join her.

Finishing an Unfinished Journey

Mr. Liang, now 53, now works at a windows company in Flushing and volunteers his evenings to call prison officials in China urging the release of detained Falun Gong adherents.When he was still in China, his two aunts were each sentenced to four years in prison. The family disclosed the prison officials’ names and phone numbers, causing it to be published on Minghui, a U.S.-based website tracking the persecution of Falun Gong. As a result, the prison guards received international calls urging them to release his aunts.

The prison officials met with the family and were very angry and afraid that their names and specific crimes had been exposed internationally. This left Mr. Liang with a deep impression.

So much so that he decided to give hours of his own time each night to call China. Every evening from 9:30 p.m. to midnight, he would call authorities in China to urge for the release of Falun Gong practitioners based on the persecution cases published on Minghui.

He has done this for over five years, sometimes six to seven nights a week. According to Mr. Liang, prison guards are now afraid of the calls because they had stopped yelling and cursing at him. He could sense the fear; they either hung up right away or listened in silence.

This is Mr. Liang’s fifth time joining the July 20 commemoration activities in Washington since arriving in the United States. He said he felt that his unfinished journey to Beijing 23 years ago was completed in America.

“I want to speak up for those persecuted in China. I want to support them, and I want to end the CCP’s persecution,” he said.