News Analysis

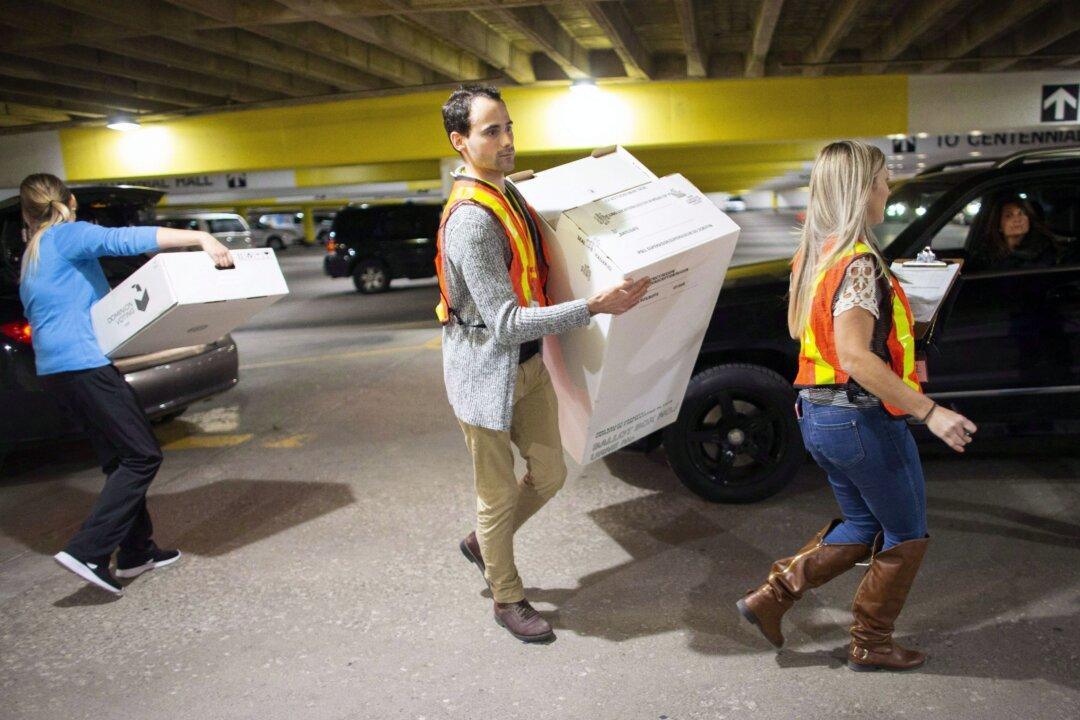

Many Canadian municipalities continue to favour online voting and computerized vote counting despite controversies around these technologies and expert warnings about cybersecurity risks and other issues.

Many Canadian municipalities continue to favour online voting and computerized vote counting despite controversies around these technologies and expert warnings about cybersecurity risks and other issues.