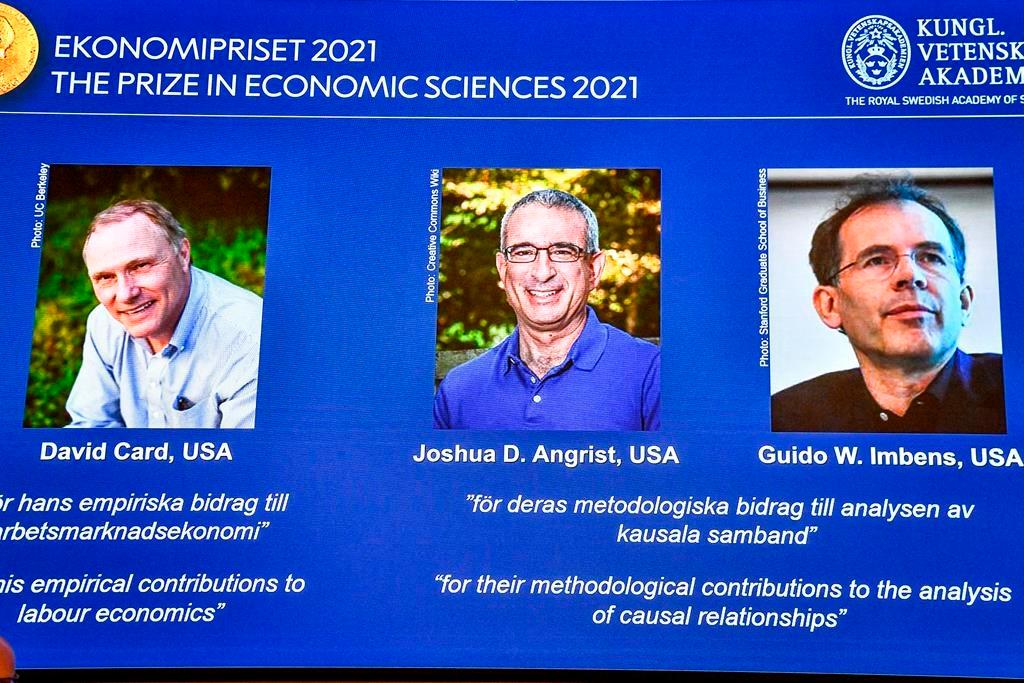

When the phone rang around 2 a.m. telling David Card that he won the Nobel Prize for Economics, the Canadian-born economist thought it was a stunt.

But when he saw the phone showing a Swedish number he thought maybe it wasn’t a joke after all.

When the phone rang around 2 a.m. telling David Card that he won the Nobel Prize for Economics, the Canadian-born economist thought it was a stunt.

But when he saw the phone showing a Swedish number he thought maybe it wasn’t a joke after all.