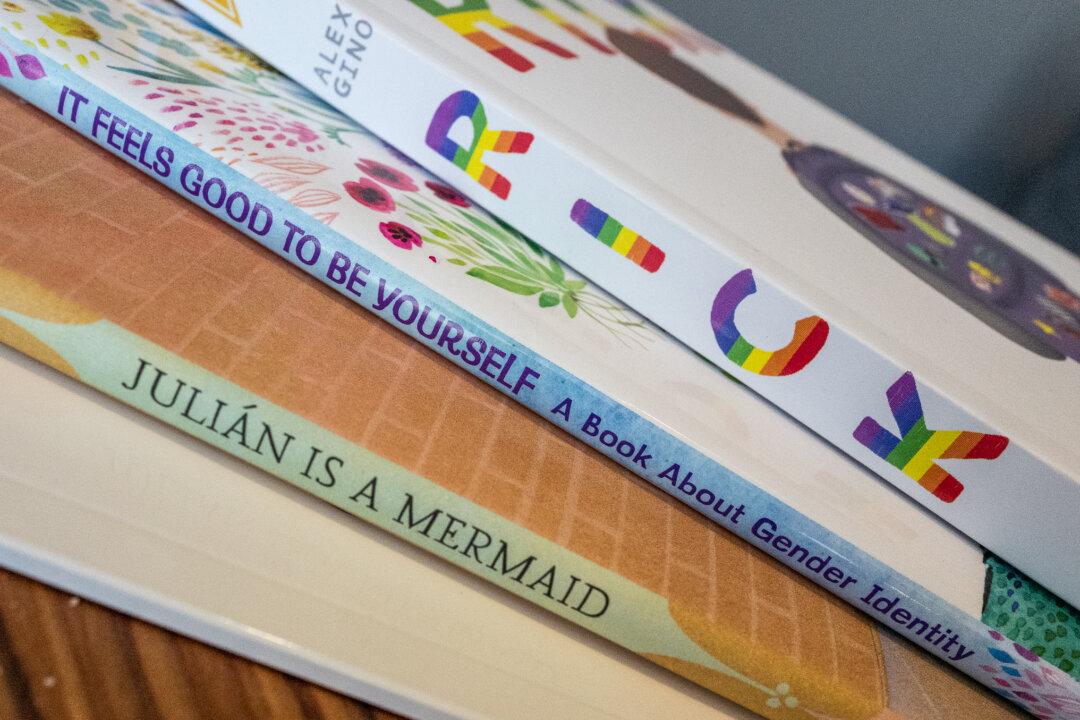

As California students head back to school this year, they may encounter books and materials promoting LGBT topics, transgenderism, and gender ideology for children as young as preschool and kindergarten.

Dozens of books with such topics are promoted for use in classrooms by the California Department of Education’s recommended literature list, under the topic “Gender/Sexuality.”