California is readying a new program that would collect data on children from before birth to adulthood.

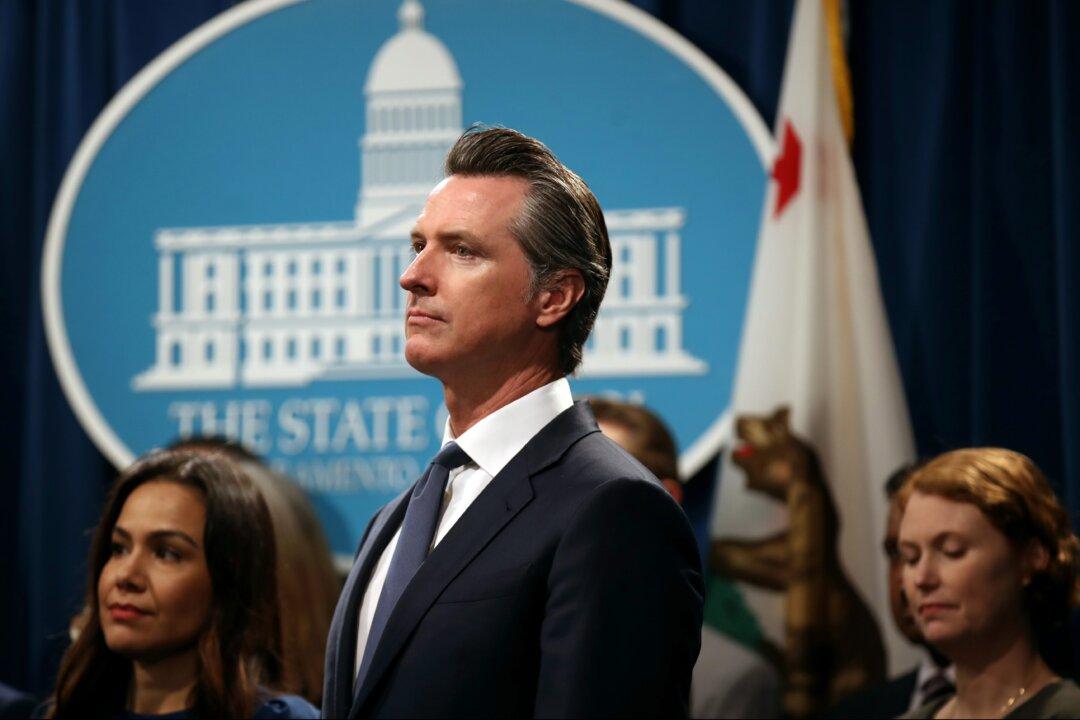

The plan (pdf), which is a central part of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s education agenda, would give the government the power to collect data from state agencies responsible for regulating elementary and secondary education, as well as childcare providers, private and public universities, financial aid institutions, labor and workforce agencies, and health and human services program administrators.