Interview with Marc Berkman, CEO of the Organization for Social Media Safety.

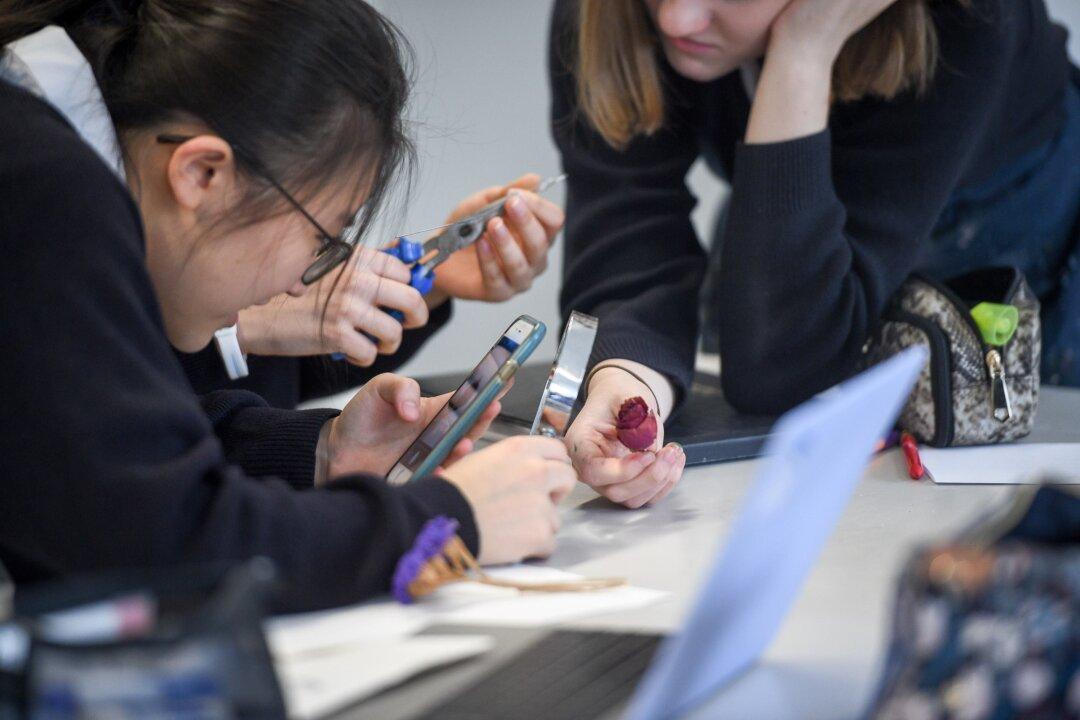

Siyamak Khorrami: There’s a trend in California that they want to ban phones in schools. LA Unified did that already, and this trend may go across the country. You guys have been involved with this. Can you tell us what’s going on with this? What’s this trend about?