News Analysis

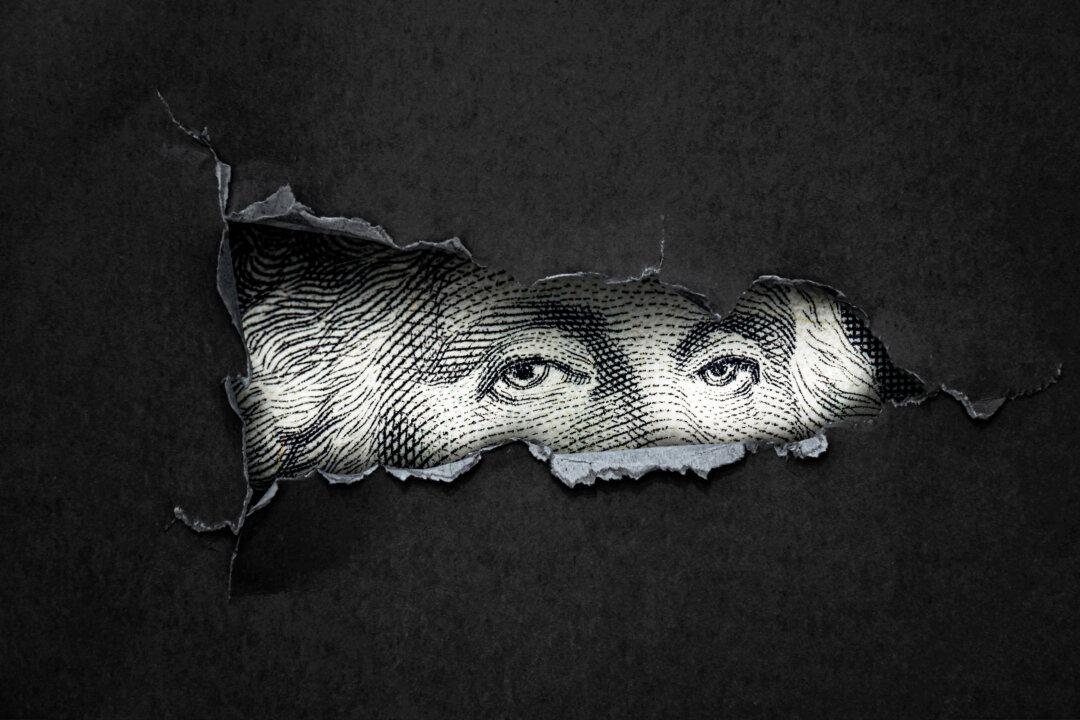

Slowly but steadily, our money is taking on a new role; in addition to its traditional function as a medium of exchange and store of value, money is increasingly becoming a means of surveillance and control.

Slowly but steadily, our money is taking on a new role; in addition to its traditional function as a medium of exchange and store of value, money is increasingly becoming a means of surveillance and control.