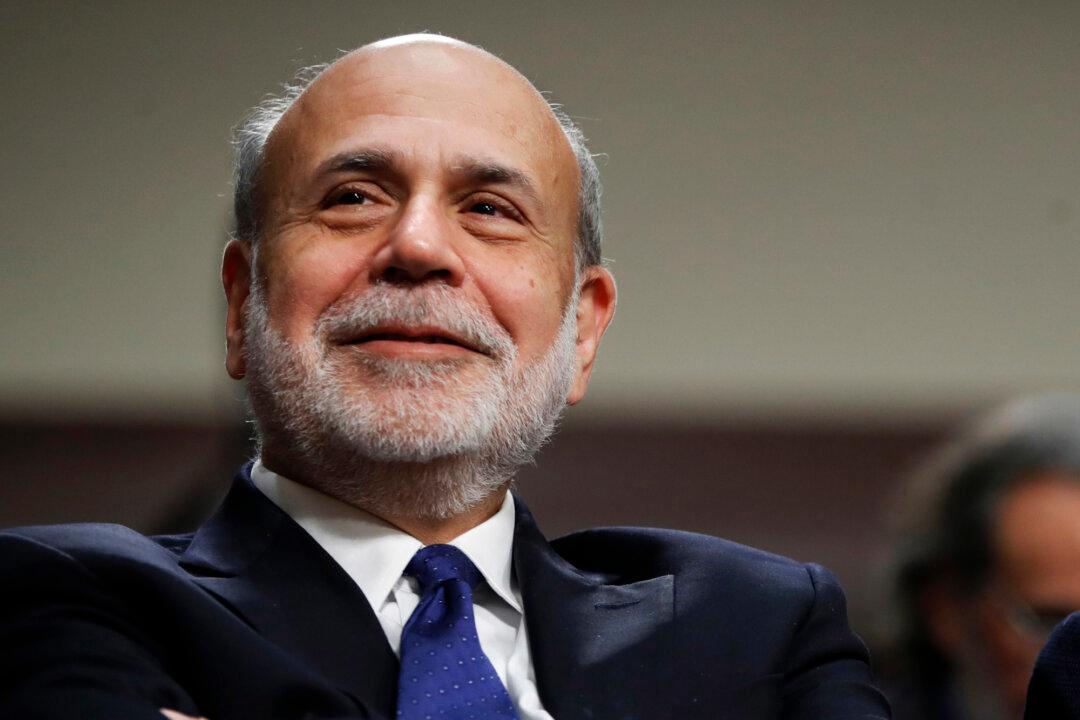

Central bankers and most economists failed to anticipate the sharp increase in inflation that began in 2021, and public policymakers were slow to respond after insisting that price pressures were “temporary,” a new paper co-authored by former Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke states.

The Fed misjudged the economic effects of pandemic-era fiscal programs, which explains why many failed to accurately forecast the inflation that resulted from the stimulus and relief measures, including the March 2020 $2.2 trillion CARES Act, the December 2020 package that consisted of $900 billion in COVID-related spending, and the March 2021 $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan.