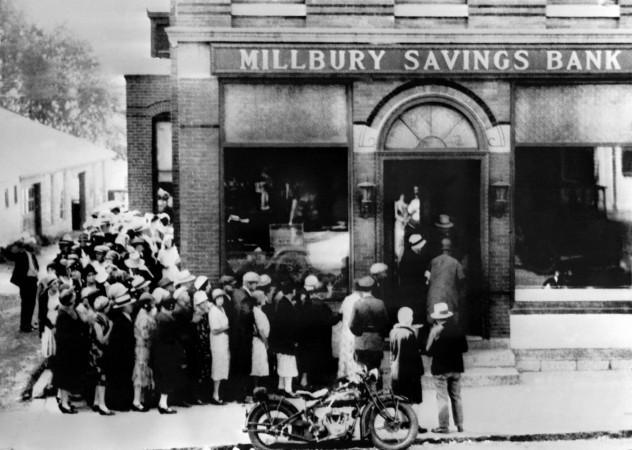

Following a string of regional bank failures over the past several weeks, bank regulators were quick to guarantee all depositors for the full balance of their bank accounts, even beyond the $250,000 limit set by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC).

At the time, the Biden administration assured Americans that taxpayers would not be on the hook.