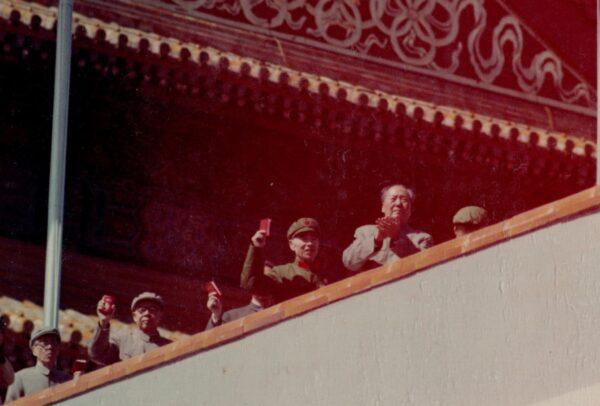

Few individuals in the world can say they’ve seen Mao Zedong in person or dined with Deng Xiaoping.

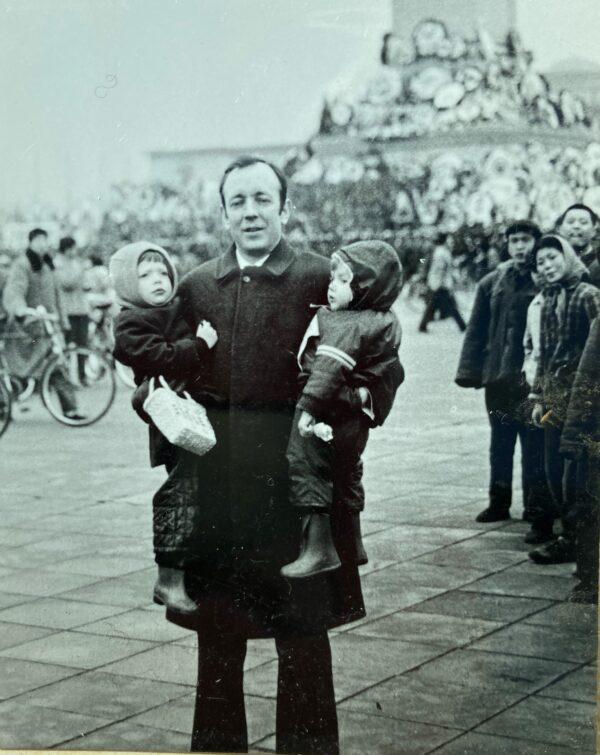

But Roger Garside has done both. In 1968, he captured a photograph of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Mao Zedong in Tiananmen Square at a time when very few Westerners had access to China, and in 1977, he dined with China’s future paramount leader Deng Xiaoping.

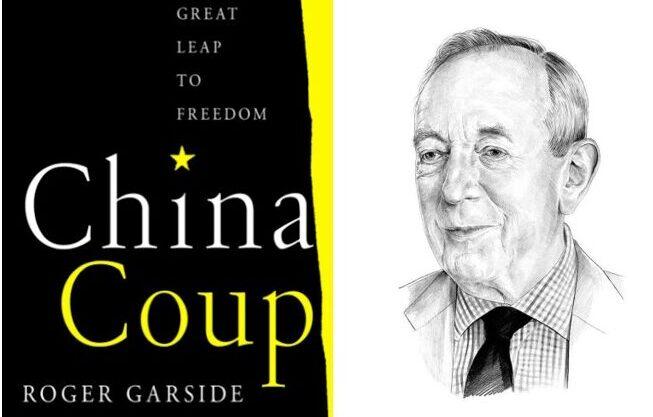

In an exclusive interview with The Epoch Times, Garside—a former British diplomat and author of the newly published book “China Coup: The Great Leap to Freedom”—looked back on his more than six decades of following events in China, and looked forward to what he predicts will be momentous change there, including potential political change and a transition to democracy.

He described in detail the senseless violence that he and other diplomats witnessed in China in the late 1960s during the turbulent Cultural Revolution, telling The Epoch Times, “We all saw terrible things.”

Despite what he witnessed in China during Mao’s reign and the developments since then, Garside said he believes—as explained in his new book—that the one-party rule of the CCP, which he calls a totalitarian regime, can soon be ended. He noted that over the decades, he’s seen evidence of aspiration among the Chinese people for political and social freedom, as well as political change, which he says the United States and its allies can help them achieve.

After attending boarding school at Eton College, Garside was conscripted into the British army at age 18 and was commissioned as an officer in the late 1950s, serving in British Hong Kong with the Brigade of Gurkhas—a unit chiefly comprising soldiers recruited from the hills of Nepal.

“I first watched China through a pair of army binoculars across the Hong Kong–China border at the time of the Great Leap Forward, when at night, in the valley below, refugees from starvation and death in the mainland were trying to escape into the freedom of Hong Kong,” Garside told The Epoch Times, referring to the disastrous period from 1958 to 1962, in which Mao made a radical attempt to reorganize Chinese society into communes and rapidly increase China’s economic output through top-down centralized planning.

The Great Leap Forward resulted in widespread famine for the Chinese people and has been estimated to have caused tens of millions of deaths in China.

Garside said that, during his year and a half as a soldier in Hong Kong, he developed an admiration and respect for the people there.

“I saw their entrepreneurship, I saw their family values ... how they flourished in a small government regime,” he said.

After graduating with a degree in English literature from the University of Cambridge following his military service, Garside decided to join Britain’s Diplomatic Service.

“I had developed a great taste for faraway places with strange-sounding names,” he said.

Returning to Hong Kong, where he completed two years of Mandarin Chinese language training, he was posted to the British diplomatic mission in Beijing from 1968 to 1970—near the height of the hysteria witnessed during China’s Cultural Revolution.

“When I arrived [in China] in May of ’68, the Cultural Revolution was still in full flood,” Garside said. “There was violence breaking out all over China, there was factional struggle at the ground level. Even the people who worked in the grocery store in our diplomatic compound, the Chinese employees there, would be dragooned into going out and marching in the streets or even around the compound, shouting angrily, denunciations of whatever the target of the week was: sometimes imperialism, sometimes Soviet revisionism, sometimes domestic targets.”

He described some of the disturbing actions that the people of China were being goaded into carrying out—in the name of party loyalty—by the CCP.

“We were reading many horrible stories of violence within families,” Garside said, “as Red Guard children were psyched up, driven, forced, [for] whatever reason, to attack their grandmothers and smash their Buddhas, maybe even join their schoolmates in dragging their grandmothers through the streets behind carts or beating old people with belts in parks. We all saw terrible things.”

Garside suggested that while the Chinese people were being whipped into a frenzy by the CCP, on many occasions, those participating in the mandatory demonstrations were feigning emotions that weren’t representative of their true character.

“I saw these people taking part [in demonstrations]. ... And I contrasted the behavior of those people in public—the show of anger, the show of outrage—I contrasted that with the people who worked in our homes as domestic servants, who seemed so different. They were personally kind, considerate, hardworking,” Garside said. “And it was as if they had two faces, two lives, two personalities. And it taught me a lot about the skill as actors which the Chinese people have had to develop under communist rule. I think they’re the greatest nation of actors in a theatrical sense.

“Their very lives, their freedom, depend upon their being able to put on a show, and they do so without a moment’s hesitation. They’ve been trained to it from elementary school upwards.”

After finishing his first diplomatic posting in Beijing, Garside earned a master’s degree in management science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and helped manage the program of lending to Thailand by the World Bank in Washington.

“When I was working in the World Bank, I saw the Asian Tigers rising,” he said, referring to the economies of South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong, which he noted were export-led and powered by dynamic private sectors.

The dynamism of the “Four Asian Tigers,” as these nations have often been collectively called, in the context of their rapid economic growth from the ‘60s through the ’80s, was in sharp contrast to the economic paralysis that Garside observed during his second diplomatic posting to Beijing from 1976 to 1979, characterized by state-owned industry and collectivized agriculture.

Garside arrived for that second posting in January 1976, just one week after the death of Zhou Enlai, who served as premier under Mao. He saw that China’s top leaders were engaged in a thinly veiled factional power struggle between pragmatists loyal to Zhou and leftist revolutionaries loyal to the ailing Mao, who would die in September that year.

In late 1977, Garside had occasion to meet and dine with the future paramount leader of China, Deng Xiaoping, while managing former UK Prime Minister Edward Heath’s visit to China. One memorable detail of the occasion was Deng’s use of a spittoon, a habit for which he was well known.

“There were these huge, white, enameled spittoons, and he would have one just in front of his armchair,” Garside said. “I’d heard about him spitting, so I took note whenever he spat, and whenever he mentioned the Soviet Union, he spat.”

Deng reached the top of the CCP in 1978, and Garside witnessed part of a brief period of nascent political liberalization, from late 1978 to 1979, known as the Beijing Spring. A key feature of the Beijing Spring was a “Democracy Wall,” upon which the Chinese people would openly post denunciations of injustice and calls for democracy that would be read, discussed, and debated. Deng initially supported the Democracy Wall but launched the first of multiple crackdowns in March 1979, shortly after telling high-ranking CCP members in a speech that the democracy movement had “gone too far.”

By the end of 1979, the Beijing Spring period was over.

Nonetheless, the short-lived Beijing Spring had provided Garside with clear evidence of a desire among the Chinese people for greater political freedom. Shortly after leaving Beijing in January 1979, Garside wrote his first book, the widely praised “Coming Alive: China After Mao,” which details this period.

His new book, published this year by the University of California Press, looks to China’s future. In “China Coup,” Garside describes in detail his vision that soon, with the help of liberal democracies using economic tools to pressure the CCP, the Chinese people will be able to make a “great leap” to freedom and democracy.

“We have great economic assets, which we can deploy in order to come together with those who want change in China. And by using them in an imaginative and bold way, both cumulatively over time and then, in a more focused, short-term way ... we can create conditions in which those within China who want change can move,” Garside said. “This techno-totalitarian [CCP] has great instruments of control, and it’s going to be extremely hard for any movement within China to achieve China’s liberation without outside assistance.”

Garside emphasized that the CCP is now a major global threat to freedom. He added that the United States and its allies are experiencing a “great awakening” regarding the true nature of the CCP.

“We have awoken to the threat from China late. But not too late. We are engaged in a fight for freedom, a global fight for freedom,” Garside said. “It’s a complex task, more complex than the struggle against the Soviet Union was because China is so deeply interwoven with us now—economically and socially. We can’t just be defensive. ... We’ve got to be a lot more active in pursuing regime change in China.”