Commentary

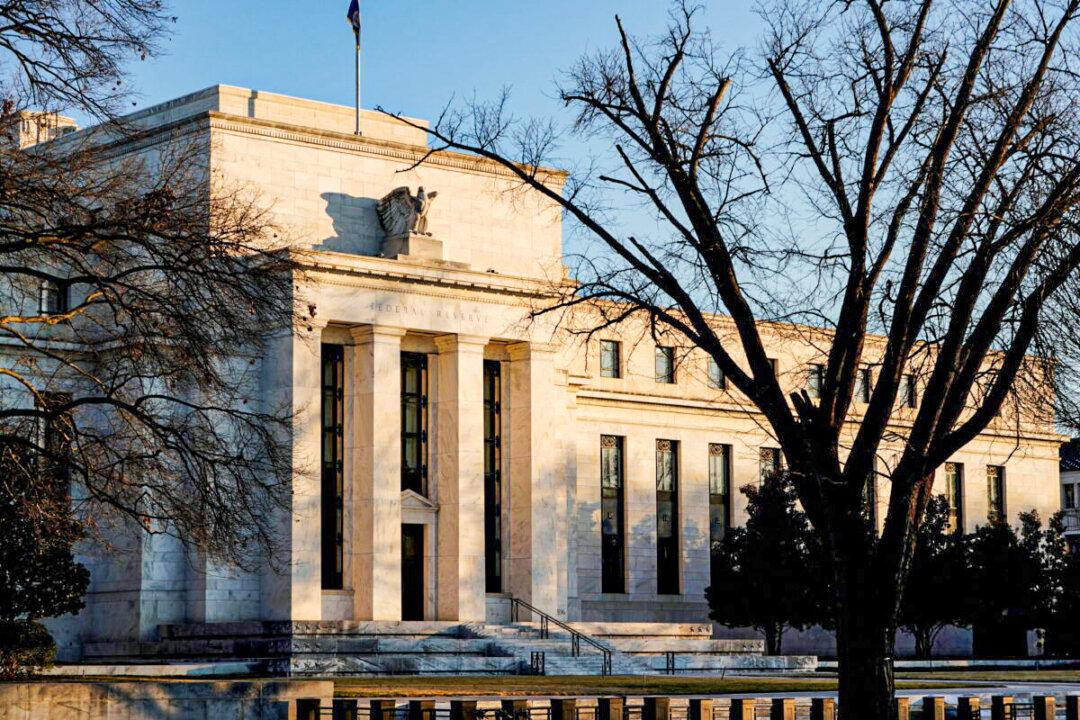

In what can be best described as a classic western showdown, on one side is the Federal Reserve, which is tasked with managing the monetary system, and on the other side are market participants, who want to keep the good times rolling. Both gunslingers came prepared, as the Fed is eager to show it can put an end to higher inflation, while the market participants believe that they can break the Fed’s will.