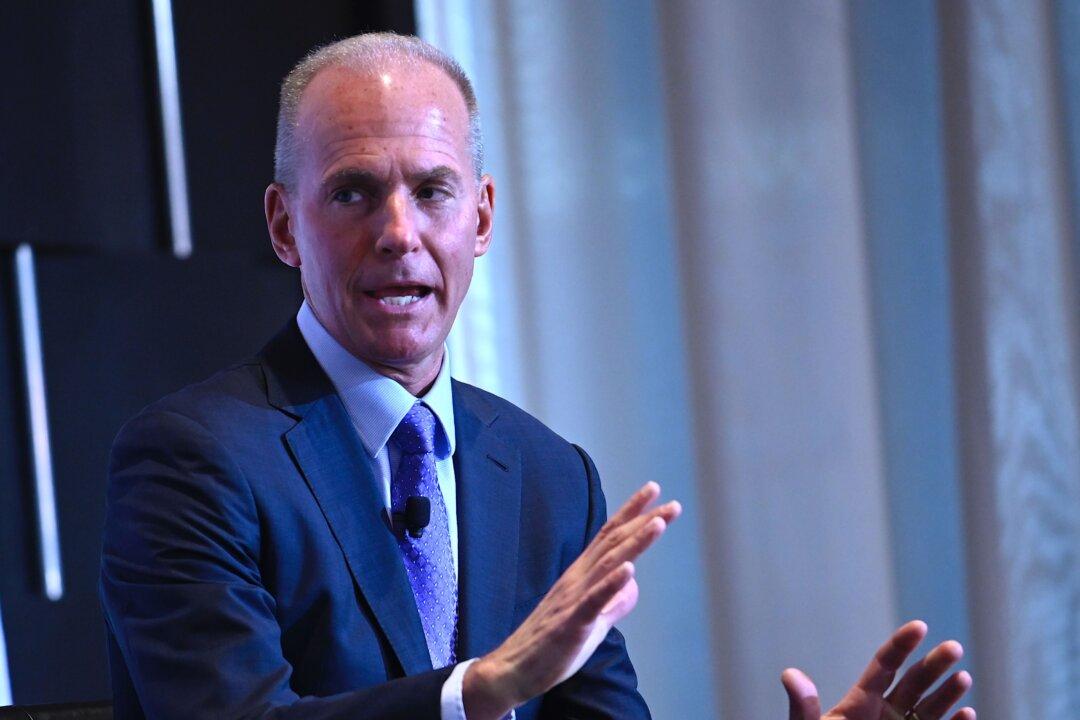

The clock is ticking ever more loudly for Boeing Co. Chief Executive Officer Dennis Muilenburg as the grounding of the 737 Max hits the seven-month mark. The board removed him as chairman Oct. 11 after the close of the workweek, saying the change would enable Muilenburg to focus on returning Boeing’s best-selling jet to service. The directors expressed support for Muilenburg but pledged “active oversight” as they handed his chairman’s post to lead director David Calhoun, who has been mentioned in years past as a potential Boeing CEO.

Last week’s shakeup weakens Muilenburg, 55, as he tries to get the Max back in the air this quarter and prepares for a crucial appearance before Congress on Oct. 30. Boeing’s reputation and finances have been battered since two Max crashes killed 346 people and prompted a global grounding, and U.S. regulators have yet to schedule a crucial test flight needed to re-certify the plane.