Commentary

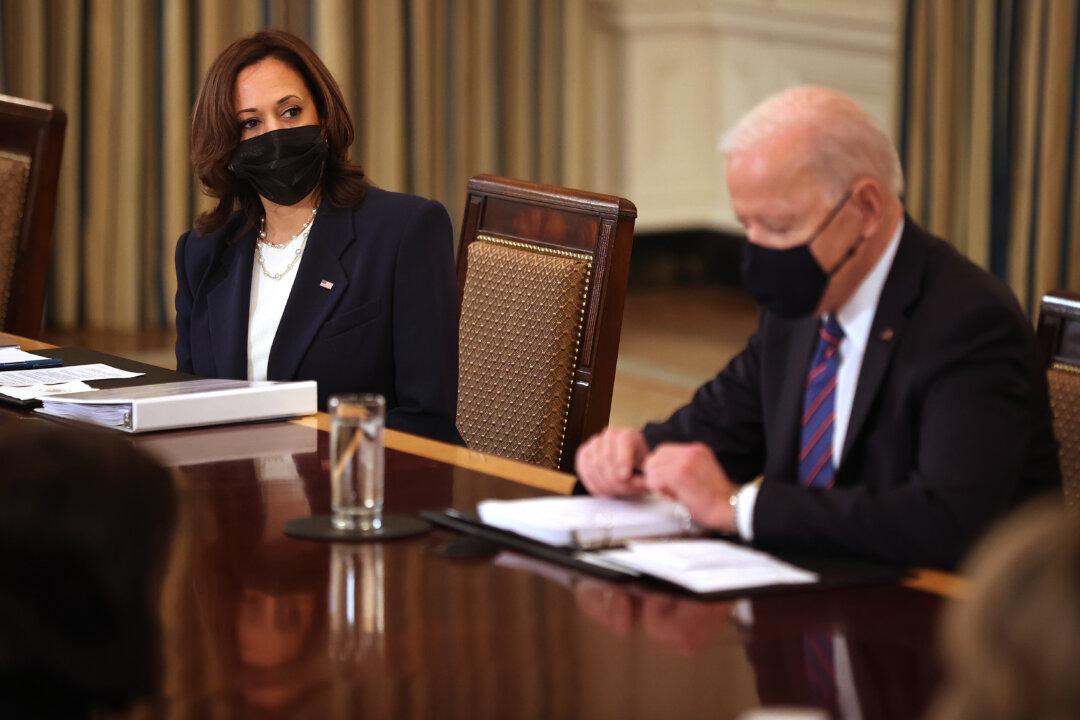

Early in the Biden administration, the president tapped Vice President Kamala Harris as his “point person” to address illegal immigration at the southern border.

Early in the Biden administration, the president tapped Vice President Kamala Harris as his “point person” to address illegal immigration at the southern border.