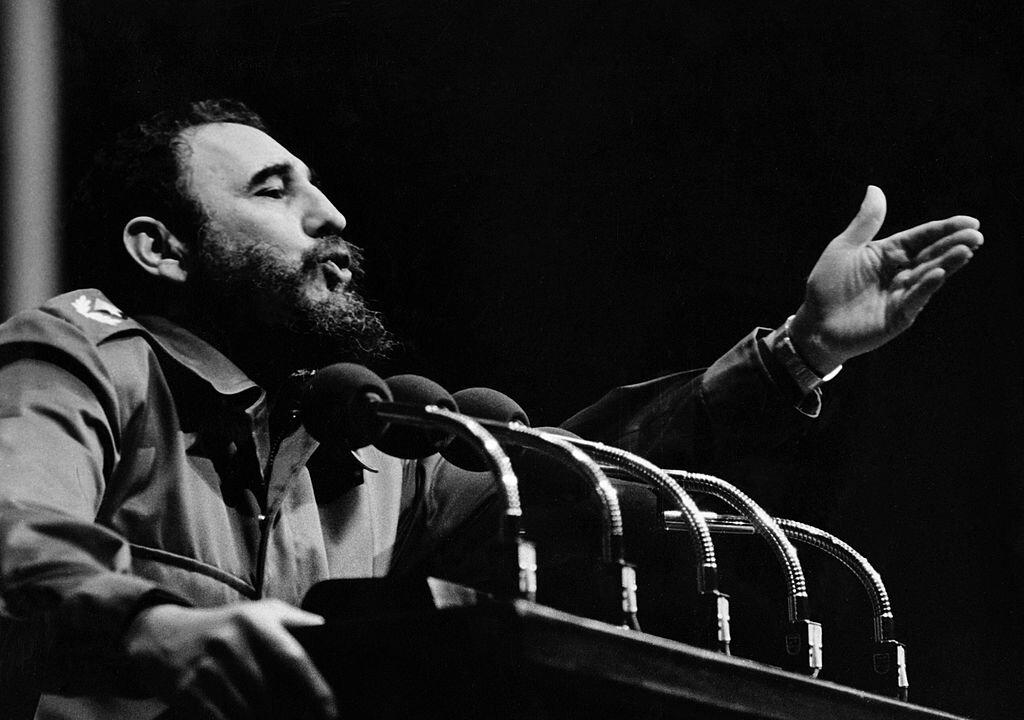

When Fidel Castro confiscated private properties in Cuba in the 1960s, both the owners and the Cuban people suffered. The winners—the young dictator and his close comrades—profited from their ill-gotten gains by partnering with unscrupulous crony capitalists.

The present-day cronies, by and large from outside Cuba, are staring down the barrel of lawsuits that seek damages for theft. Since May, the Trump administration has, as explained by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, given the victims of confiscation in Cuba the opportunity to right the wrongs of decades ago. The cases fall under the 1996 Helms-Burton “Libertad” Act.